“Starving for Order”: A Conversation with Ted Kooser

For more, read two new poems by Ted Kooser.

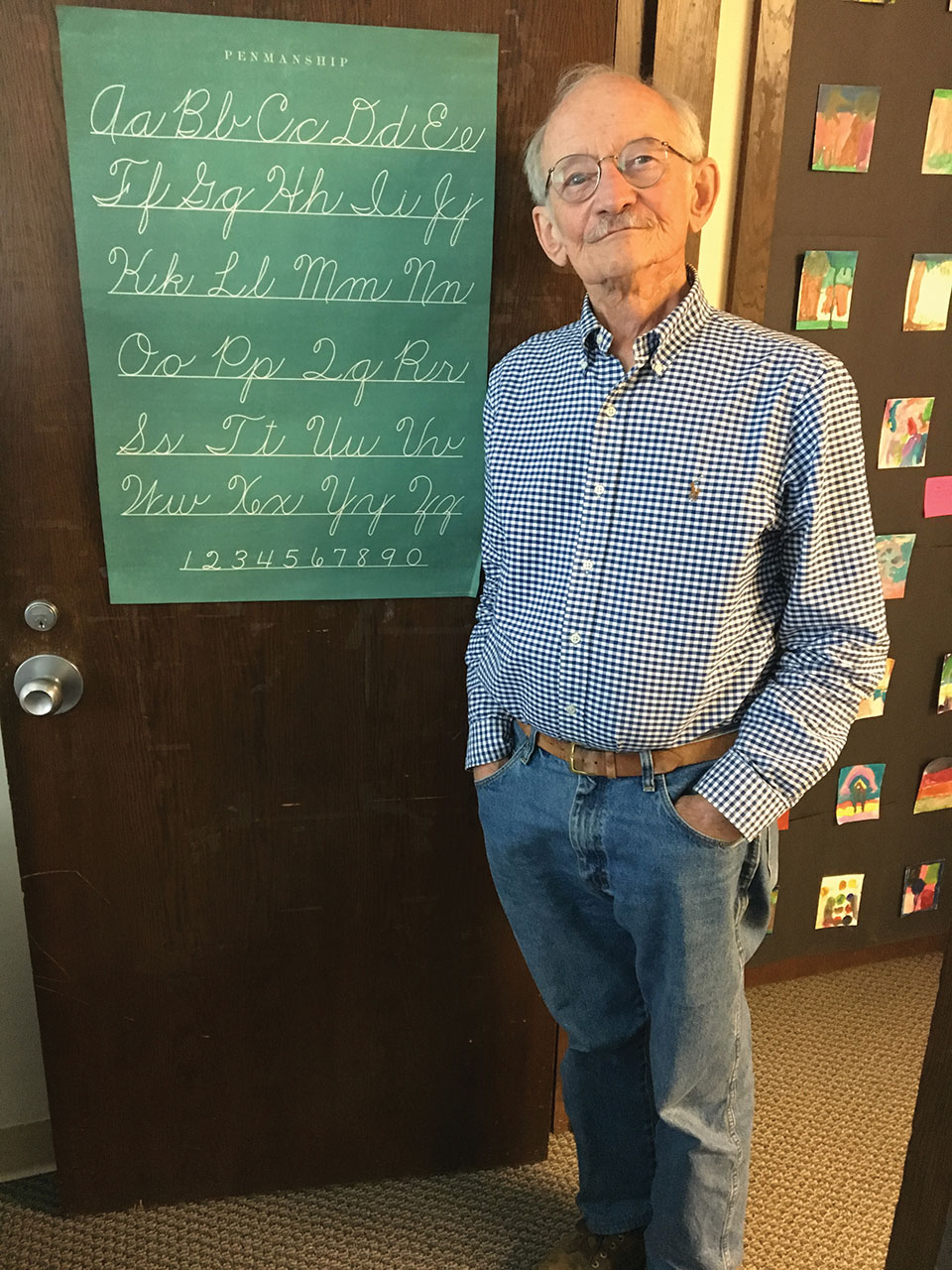

While in Lincoln to attend the recent Nebraska Book Festival, I sat down with Ted Kooser (b. 1939) to discuss poetry, belief, and tolerance. A former US Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry (2004–2006), Kooser is currently Presidential Professor of English at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln. His many awards include a Pulitzer Prize in Poetry (2005). Kindest Regards: New and Selected Poems is forthcoming from Copper Canyon in 2018.

Daniel Simon: “On every topographic map, / the fingerprints of God.” That couplet appears in Braided Creek (2003), your “conversation in poetry” with Jim Harrison. Is there a sacred geography in your poetry?

Ted Kooser: I described the place most sacred to me in my prose memoir Lights on a Ground of Darkness (2005), Daniel, and looked at it again in my children’s book The Bell in the Bridge (2016). It’s my maternal grandparents’ house and roadside Standard Oil station at the edge of Guttenberg, Iowa, a magical place when I was a boy. I think my true center is there.

Simon: You write so sweetly about John and Elizabeth Moser, your maternal grandparents, especially in your memoir. And you’ve a written at least a couple of poems about Elizabeth’s funeral in January 1962, when it was twenty-two below. The striking visual in those poems for me is the thawing barrels in the cemetery, which the two men stoked all night in order to soften the ground for the burial.

Kooser: And you could see that from the house. The dining room on that house had windows facing west, and it overlooked a patch of corn that was about a hundred yards across. A creek ran through there, and then the land sloped up to the cemetery. It was a wooded hillside, but in the winter the trees were all bare. And you could see that smoke up there—the graves are just over the top of that hill.

Simon: You write about your grandfather sitting there on the morning of the funeral, already dressed, looking up the hill toward the cemetery. That night, you slept in your uncle Elvy’s bed, and the wind just howled through the cracks in the windows and through the cemetery.

Kooser: I’ll never forget Elvy walking along behind the coffin. His mother was so dear to him; she had protected him all those years but was a little too softhearted and let him eat things he wanted but shouldn’t eat. Although he was diabetic, she always had cookies and cakes for him. At the funeral, they had to carry her coffin slightly downhill in the snow and ice, and Elvy stumbled along behind, wanting to put his hand on the coffin.

Simon: You would have been in your early twenties then? Obviously, when you speak of sacred geography, you invoke childhood memories but also returning to Guttenberg later in life . . .

Kooser: Yes, I was twenty-three when Grandma Moser died. You know, I think part of the attachment to my mother’s family, Daniel, is that my Kooser grandparents didn’t live very long. My grandfather Kooser died when I was two, and my grandmother when I was ten. I have memories of her, but the Mosers lived on and on and on. Granddad died in ’72, so I would have been thirty-three, something like that.

Simon: There’s a scene in the memoir where you write about Uncle Elmer and Uncle Elvy driving down the road in this ’49 Chevy with a fishing pole sticking out the back window. As a reader, I thought that was a striking visual detail.

Kooser: Elmer Morarend had been one of those very, very shy German farm kids. As an older man he hardly would say a word and had a real squeaky little voice. . . . That world of the Mosers and Morarends is really at the center of everything: my emotional heart is always that family. And to this day, when I see parents raising disabled children like Elvy and I see them out in public, boy, that really hits me hard. The other day there was a television show about a girl who had some kind of palsy; she was elected homecoming queen, and I found myself weeping uncontrollably. Everybody gathered around her . . .

Simon: In your essay on “Metaphor and Faith,” which uses the extended metaphor of Robert Frost’s “The Silken Tent” as an analogy for faith, you write: “Every religion, and each person’s private faith, leans like a ladder against this presence that stands beyond the reach of our intelligence” (Seminary Ridge Review, Spring 2011). Is poetry one of those ladders for you?

Kooser: Writing poetry does feel to me like prayer. When I’m writing, early in the morning, I’m oblivious to everything around me, and to time. I guess for those moments I’m on a ladder magically leaning on air.

Simon: In that same essay, you write about being “swept up and away” into the “enormous compelling mystery” of belief. Yet isn’t Frost’s sonnet as much about our “bondage” to “every thing on earth” as the “pinnacle to heavenward”?

Kooser: When I wrote that about the Frost sonnet I wasn’t thinking about what might be his meaning, but instead simply stealing his metaphor. It’s a poem I’m very fond of but like many of my favorite poems, it’s what I make of it that’s important, not what the poet might have meant. I think once a poet gives a poem to the world, he, say Frost, gives up all control, and the reader can use it as he or she wishes to. That may be to find meaning, or it may be to enjoy the play of the language.

Simon: When it comes to Frost’s language, I like to think that the play itself is the meaning. (He has a poem called “To Earthward” that begins: “Love at the lips / Was touch as sweet as I could bear.”) Would you like to say a little bit more about the play of language in Frost’s poetry or your own?

Kooser: Part of that comes from my own experience as a writer and how those poems come together. And the way I work is that I’m sitting there in the morning, just randomly jotting down things in my notebook, and a particular metaphor will occur to me. And then what I do is I dress the metaphor. I add to it, as much as I can add without it exploding—or imploding. So the metaphor is at the center of the poem, and I suspect that the silken tent metaphor in that Frost poem is the point from which the poem pulls out and away from.

You can’t plug a metaphor in a poem. It has to be organic. For me, that’s really where the magic is. The space between the tenor and the vehicle is like looking into something beyond us, the magnificent thing which happens in that association.

I have grad students who will be working on a draft of a poem, and they will say, “Don’t you think I ought to put a metaphor in here?” And well, you can’t plug a metaphor in a poem. It has to be organic. You know, there are pretty successful poets who really can’t do metaphor. But for me, that’s really where the magic is. The space between the tenor and the vehicle is like looking into something beyond us, the magnificent thing which happens in that association.

Simon: Which Aristotle recognized, way back in the Poetics: the genius of metaphor, the space where that kind of synapse happens.

Kooser: You bet. Robert Bly wrote some things about that years ago, how the farther apart the tenor and the vehicle are, the more powerful the metaphor is. If the Big Bang is true and everything originated at that point and emanated out from it, then all these things are related. These are moments of recognition: that this thing is like that . . .

Simon: Gerald Stern has said, “I suspect that the actual writing, the continuous writing, the writing over and over again, the commitment, is a kind of devotion. Maybe it’s not the devotion of a priest; it is certainly the devotion of a mourner. I’m in complete agreement with Simone Weil’s statement that ‘absolute unmixed attention is prayer.’”[1] Is your writing, as a form of paying attention, such a devotion? The title of Lights on a Ground of Darkness comes to mind: perceiving light against the pattern of darkness. Or “the puff of yellow pollen” that appears in “A Glimpse of the Eternal” (Delights & Shadows), that kind of momentary perception. And in Winter Morning Walks (2000), I see observation in those poems as a type of reverence.

Kooser: Dan Gerber, who is a friend of mine and a very good poet, thinks that Winter Morning Walks may be my best book. Those poems are really good examples of what we’re talking about. I would go out and come back and sit down, early in the morning, and some association would have come to me, and they spin out from that, one after another after another, driven by anxiety . . .

Simon: You were recovering from surgery and radiation therapy for cancer at the time, right?

Kooser: Yes. I always avoid thinking of writing as therapeutic, but that’s exactly what those poems were. I’ve given a lot of copies of that book to medical students, and I’ve given presentations talking about the fact that if you can make some kind of order when you’re dealing with cancer, which is chaos, if you can find a small piece of order in that, there can be a great deal of comfort in it. During the course of all this I had asked my doctor, “If this tumor comes back, what will happen?” And he said it will follow a predictable course: it will go down your neck and into your thorax and from there on. As horrible and as frightening as that was, there was some assurance in the fact that there is a pattern to cancer. I was so starved for order that I could see order in that.

Simon: Walking out into the darkness, walking back, putting one foot in front of the other, and then the lines on the page just have that sense of security.

Kooser: The composer Maria Schneider has had a lot of success with that “man with the moon on a leash” poem [the November 18 poem from Winter Morning Walks, which Schneider set to music for soprano Dawn Upshaw and won three Grammys for]. She’s coming out here next spring to see the sandhill cranes.

Simon: I had hoped to make it back this spring to see them. When Don Welch and I were emailing back and forth about the Nebraska Poetry anthology last year, before he passed, I told him that my idea of the Elysian Fields was to go out to Kearney and see the cranes with him.[2]

Kooser: When Don was in his last days, I heard from the family that he had gotten somebody to adopt all his pigeons. And one day Kathy and I went down to Branched Oak Lake for an early morning walk. Nobody was around, and out on the point, we came upon a white pigeon, sitting in the parking lot, with scarlet underwings. Obviously not a wild pigeon. And I thought, This is it . . .

Simon: You’ve told me that Don’s poem called “Funeral at Ansley” (Dead Horse Table, 1975), with its autumnal wind coming through the cemetery during the funeral, always makes you think of Harvey Dunn’s painting I Am the Resurrection and the Life (1926). Do you think about poetry and painting a lot, as an analogy for your own work?

Kooser: Yeah, I suppose it’s because I have this love of painting. That’s probably the reason my work is so visual. But it’s frequent for me to think of paintings while I’m writing. That Harvey Dunn painting, and many of his other marvelous paintings, are in the permanent collection of the art museum at South Dakota State in Brookings, and would be worth a side trip sometime when you’re back in our area.

Simon: You do have these great visual moments that jump out in your prose and poetry which reveal your painterly eye. I’m thinking of the county courthouse in Lights on a Ground of Darkness, where you notice the red scarf of a woman leaning out the window. And in “A Winter Morning,” you write: “A farmhouse window far back from the highway / speaks to the darkness in a small, sure voice. / Against this stillness, only a kettle’s whisper, / and against the starry cold, one small blue ring of flame” (Delights & Shadows). To me, this poem embodies the prophecy of the everyday in your work, in which God is not in the wind, the earthquake, or the fire (1 Kings 19:11–12) but in the “still small voice” of a kettle on the stove. What accounts for such an aesthetic in your work?

Kooser: You’re correct, Daniel, in seeing what I’m up to in that poem. I really do believe that God is in the details and, in this instance, in the ring of flame under the kettle. Also, as a writing strategy, a reader can “see” a kettle on a stove but can’t see an idea.

Simon: In terms of a writing strategy, do you feel a kinship with other writers in this regard?

Kooser: I have noticed a lot of poems that are like that, from time to time. I was really taken with a poem on The Writer’s Almanac this week by Anya Krugovoy Silver. It’s a poem about a woman who has a hole in the end of her sock and has pulled her sock and then tucked it under so that no one can see the hole. It seems to me that that is such a powerful thing, just to be able to see that tiny detail. I love that kind of simplicity in poetry.

I was so proud of myself when I wrote the poem called “Two” in Splitting an Order (2014) about running into the two men on the staircase in the parking lot. Because it has that: it has nothing in it other than that moment where we pass.

Simon: Where the conjoined hands of the two men—the son in his sixties and his father in his eighties coming down the steps—separate to let you pass, like a river flowing around a sandbar . . .

On another note, I’m struck by the “little system[s] of . . . care” that pervade your poetry (“Flying at Night”). Yet the human presence in your verse is often marked by loss. Is language (art) enough to compensate?

Kooser: I wish that a poem could compensate for a loss, but it can’t, at least completely. But it can help by clarifying feelings. When a person wakes at two in the morning, obsessing about something, perhaps something he should have said and didn’t say, going over it again and again and again, if he will get up and write down what he’s been thinking, the obsession will almost always go away and he can get back to sleep. For me, poetry is a way of clarifying and specifying feelings.

Simon: Talking about feelings, I’m reminded of your poem “The Screech Owl,” with the line about that “small hope / from the center of darkness / [calling] out again and again” (Delights & Shadows).

Kooser: That’s probably my favorite poem. There again, no extraneous material is in there, just that little thing.

Simon: You often ascribe these anthropomorphic qualities to nature. The feelings that come through these poems, to me, are always very grounded in that quality of observation. Especially in your poems about birds: I see them as a metaphor for the poet’s imagination, the spirit wanting to escape mortality or something that’s a weight in our lives.

Kooser: You’re too young to remember this period, but part of the awful influence of Eliot and his people was that they were so opposed to the pathetic fallacy, the notion of assigning qualities to inanimate things. And I rebelled against that from day one. I figured screw it, this is where the fun is: the real delight in finding life in a stone. What can be wrong with that? I often wonder if after they had set down their rules they didn’t regret it a little bit, because it was so limiting.

Simon: So often in your poems there’s an image, like the tractor in the doorway of the church (“The Red Wing Church”) or in “Abandoned Farmhouse” (both in Sure Signs), famously, where you set a scene that evokes a former human presence which has become an absence. The feelings that come through in the absence of what was once there are especially powerful in your work.

Kooser: I can’t remember whether I told you about this book that Connie Wanek and I put together, which Candlewick Press has accepted, called Making Mischief: Two Poets at Play among Figures of Speech. In the collection, it doesn’t indicate who is the author. We didn’t collaborate on any of the individual poems, but the whole book is a collaboration. There are about twenty-five poems, maybe thirty, in there, and they’re all that way—they’re all at play in that way, and it was really a lot of fun. We sent it to Candlewick not feeling confident whether they’d really be interested in it or not, and they liked it a lot. That’ll be out in about eighteen months.

Simon: You did that with Jim Harrison in Braided Creek, where you were exchanging postcard poems, and in the final gathering of the book you didn’t attribute specific poems to one writer or the other.

Kooser: It would have really made that book very stiff if those poems couldn’t flow together like that. What happened was, we’d been exchanging this stuff for years with no idea of a book whatsoever, and Jim, who was always ready to have another book because he was making his living with books, said let’s do a book of these, but you put it together. So it was up to me. I had all the poems on 3 x 5 index cards, and I stretched them out through the length of our house and kept moving them around until I arrived at something that felt like it had some sort of overall sweep to it. But I didn’t want a poem by Jim and a poem by Ted and a poem by Jim and a poem by Ted, so in some cases there are two by him and one by me, or one by him and two by me.

It’s funny, in one of the first reviews that came out of that book in a literary magazine, the reviewer said, “Those of us who are familiar with the work of Ted Kooser and Jim Harrison can easily identify who wrote which poem.” And then he quoted a poem and said this is clearly a Harrison poem, and it wasn’t.

Simon: Well, I’d like to think that the poem about the topographic map being the fingerprint of God was one of your poems.

Kooser: Yeah, that was one of mine.

Simon: Now I can’t look at a topographic map and not see that fingerprint on it.

Kooser: Well good, I’m glad it works that way. I’ve probably told you that years ago I published this little “Spring Plowing” poem about the mice moving out of the field into the fencerow (Sure Signs). And a woman from Omaha saw that poem in a literary magazine and wrote to me, telling me that she’d never pass a field in the spring without thinking of those mice, and immediately I thought, “Boy, this is what I want to do.”

Simon: In your poems, God often appears as a benevolent watchman: he can be glimpsed walking the bean rows, cupping the heart of a turtle, or bemusedly watching us “make our way across” the road like a family of wild turkeys. Yet your poems often touch on “the center of darkness.” What consolation does an avuncular God provide against that darkness?

It’s very hard for me to imagine a God who has taken a personal interest in what one old man in rural Nebraska is doing or thinking, but it’s fun to imagine him being that kind of a spirit, walking among us, amused by our foibles, shaking his head at our stupidity.

Kooser: First, it’s very hard for me to imagine a God who has taken a personal interest in what one old man in rural Nebraska is doing or thinking, but it’s fun to imagine him being that kind of a spirit, walking among us, amused by our foibles, shaking his head at our stupidity. I like your use of “avuncular” in that an uncle isn’t quite as invested in us as is a father or mother. I liked my uncles and great-uncles, who weren’t going to discipline me, or restrain me, but were just interested in me for who I was.

Simon: In “On the Road,” the pilgrim-poet kicks a quartz pebble, picks it up, and “almost see[s] through it / into the grand explanation” (Delights & Shadows). He quickly puts it down, however, and keeps walking. Do the “grand explanations” frighten you?

Kooser: Once in a while I get a rare glimpse into something beyond our world, often through the window of a coincidence. If in fact everything in the universe originated in a speck of dense matter, exploding outward and still in motion, then everything has to be related, no matter how far afield the two elements are. Coincidences seem to me to be glimpses into those relationships. In the poem you’re referring to, it was as if I had glimpsed something so enormous that it was frightening, and I turned away.

If in fact everything in the universe originated in a speck of dense matter, exploding outward and still in motion, then everything has to be related, no matter how far afield the two elements are.

Simon: How so? Could you say more about that?

Kooser: A parallel example would be when I took a philosophy course as an undergraduate, and it scared me. I don’t know who we were reading at the time, but I began thinking about what I was thinking about what I was thinking . . . and I got caught up in this sort of vortex of stuff that I couldn’t quite break out of. And it just scared the hell out of me. It’s that same kind of fear: I’m not sure I want to look beyond that point or look beyond what I can see. I can sense things out there, but I don’t want to be out there with them.

Simon: Pulling back from the abyss?

Kooser: I don’t know. I don’t think I can articulate it very well. There’s a huge empty void out there, and I don’t want to get there. I want all these things in front of it.

Simon: The theme for our November issue is “Belief in an Age of Intolerance.”[3] What can poetry teach us about tolerance?

Kooser: Tolerance in physics, as I understand it, sets acceptable or understood limits for deviations, and civil behavior also exists between agreed-upon limits. I think poetry can illustrate or display examples of those tolerances. My poem “Two,” which we talked about earlier, is about how we accept and accommodate each other. It’s a favorite poem of mine because of its apparent simplicity. But it isn’t simple, at all. I was pleased that David Barber at The Atlantic seemed to see in it that complexity in the presence of the simple.

Simon: Is there anything else you’d like to add in that regard?

Kooser: What I might say is that I see writing poems and painting pictures as being affirmations of life. And I don’t like art, poetry in particular, in which judgments are being made about others. So much topical poetry is that way. From time to time somebody might say, “You don’t write political poems. You don’t write about what’s going on in the world. You really ought to do more of that.” Well, I can’t remember who it was, Stanley Kunitz perhaps, who said that poetry in itself is its own form of subversion. In its subversion, poetry stands apart. I haven’t worked that out very well . . .

Simon: In terms of poetry as affirmation, so often we read poems that are too much about the darkness, or all about political disorder, that it’s refreshing to read poems about accommodation, poems that represent, as you said, the more fundamental human relationships that tie us to one another.

Kooser: I did recently write a poem about the president. I emailed it to some people, and it went on beyond where I thought it would go. I’m glad that people fastened upon it and liked it, but I’m still not terribly comfortable with such a topical poem.

Simon: I’m reminded of the great pinochle gathering in Lights on a Ground of Darkness, where you write about all the relatives, the uncles and aunts coming together. That in itself is an affirmation of community: gathering around the card table, and the elaborate ritual of your grandfather getting out the two decks of cards and shuffling them, while your grandmother prepared refreshments for the company. It reminded me a lot of my own grandparents, our card games and gatherings . . .

Kooser: I wondered at the time when I was a kid what the fascination was with card playing, and when I got to be a grown man I realized that part of it was that it didn’t cost any money. They didn’t have to spend anything to do that—they could have a really nice evening and didn’t have to spend a dime.

Simon: And the game itself can be just an excuse to get together and visit, to enjoy each other’s company.

Kooser: And personalities would come out and differentiate themselves. When they would let me play, if I was a little bit slow getting my cards in order, Ella Borcherding, who was a cousin of my mother’s, would whack me on the knuckles. Daniel, let’s let your readers know that Ella was like that, somebody who’d rap a kid on the knuckles if he was too slow!

Simon: We never played pinochle. It was always ten-point pitch or skat, a game of thirty-one, which was always fun for the younger kids as well as our parents and grandparents, aunts and uncles. I have lots of great memories of those kinds of get-togethers as well.

Kooser: A few weeks ago I drove up to Red Wing, Minnesota, to do a reading there. Robert Hedin at the Anderson Center had a book coming out, so I went up there to help him launch the book. And I drove through Guttenberg and stopped at the house, which is now the office for a nursery. My granddad’s station has been gone for years—they tore it down. The nursery itself is a separate building, and I suppose they use the house to keep the books and do that kind of thing. I stopped and talked to the owner, and God, the change is so incredible. You know, when I was describing that strip of corn between the house and the cemetery, that was low ground, and Miners Creek ran through it. When the Mississippi flooded, the water would back way up into that creek and fill the basement of my grandparents’ house. They had a drive-down driveway with a garage underneath the back, and there would be standing water there, sometimes for weeks. I said to the woman, you’ve filled it in back there, and she said they had put in ten feet of fill dirt all the way back. So they brought in tons and tons of earth to cover that area up. So that back porch my grandmother used to throw the dishwater off of, down into the ditch, which I describe in my poem “Dishwater,” now that back stoop looks straight out. To think of somebody going to all that effort and expense!

Simon: When the river could wash it out on a whim. How far was their house from the actual banks of the Mississippi?

Kooser: A quarter of a mile. It was typical river bottom, pretty heavily wooded. So you couldn’t actually see the river from the house, even in the winter. But it was right out there, and you could hear the boat traffic going up and down. There was a railroad track that came up on the other side of the highway from my granddad’s station too, and when the trains would come in, going north along the river, the engineers would blow the whistle and wave at my granddad, who would be sitting in his gas station behind the window and would wave back. And I remember thinking, Wow! My grandfather is really important!

Simon: So the county seat was actually in Elkader, right?

Kooser: That’s right. Elkader is the town in “Pearl,” the poem about my mother’s cousin (Delights & Shadows). I had a very nice compliment from B. F. Fairchild about “Pearl.” I had read it somewhere in public, maybe at the Dodge Festival, and Fairchild came up to me afterward and said, “If you had written only one poem, that one would be enough.” I felt really good about that. [An adaptation of the poem, directed by Dan Butler and starring Butler and Frances Sternhagen, can be seen on YouTube.]

July 2017

Footnotes

[1] Gerald Stern, “The Devotion of a Mourner,” in A God in the House: Poets Talk about Faith, ed. Ilya Kaminsky & Katherine Towler (Tupelo Press, 2012), 24–25.

[2] Welch wrote, “I have been having some health issues, but if I can help with the launch of the book in Kearney, I certainly will. Lord knows, I have scheduled enough of these over my teaching and writing lifetime at the university here, and the Museum of Nebraska Art would be a great place, especially its main gallery, to welcome a book like this and to present it to people in central Nebraska. I would love to get my former students in the book to come back to Kearney for a joint appearance and reading. Now that would be something. I could then go off to the Elysian Fields where the wind through the tall grasses produces a dulcet pentameter” (email to Daniel Simon, May 30, 2016).

[3] In 1828 Goethe remarked: “These journals, as they reach a wider public, will contribute most effectively to the universal world literature for which we are hoping. There can be no question, however, of nations thinking alike. The aim is simply that they shall grow aware of one another, understand one another, and, even where they may not be able to love, may at least tolerate one another.” For years this quote appeared on the masthead of WLT.