Co-translating Hanoch Levin, the “Beckett of Israel”: A Conversation with Jessica Cohen & Evan Fallenberg

Although Hanoch Levin (1943–1999) is arguably Israel’s most important playwright, his work is almost unknown in the English-speaking world. Jessica Cohen and Evan Fallenberg, both acclaimed Hebrew-English translators, were recently commissioned by the Institute of Israeli Drama to undertake a translation of five of Levin’s plays (The Thin Soldier, Walkers in the Dark, Krum, The Child Dreams, and The Lamenters) into English. I met with them in Tel Aviv, Levin’s hometown, to speak about the joys and challenges of translating what are considered to be classic works of Modern Hebrew, their decision to co-translate, and the anticipation of making the plays accessible to English-speaking directors and audiences.

Janice Weizman: Who was Hanoch Levin?

Jessica Cohen: He was, and probably still is, Israel’s best-known playwright. If you stopped someone on the street and asked them to name one Israeli playwright, the name that they would most likely come up with would be his, which is interesting because he was also controversial, both politically and in terms of his aesthetics. He was not a mainstream kind of creator. He was very far on the left—that’s the way he first became famous. Right after the ’67 war, when he was really young, he put on a series of satirical political sketches that, due to the controversy they caused, were subject to a lot of public criticism and protest and ultimately taken off the stage. He was always on the margins politically, but he nevertheless became Israel’s national playwright.

Evan Fallenberg: He’s often called the Beckett of Israel, or the Pinter of Israel.

Weizman: Could you say a little about his work and his dramas in particular?

Cohen: They’re hard to categorize, which is one of the reasons that I think they haven’t done well in America. I know that in literature, American audiences want things to be labeled. They need to know which shelf to put it on in a bookstore, and the same goes for plays. They figure, “I’m going to see a comedy, it’s going to make me laugh.” But those aren’t the kind of plays that Levin writes. Even his “tragedies” have comic elements in them, and his comedies often have pretty sharp social commentary or political aspects, so they’re hard to fit into one box. So, for example, you’re translating a play, and it appears to be working in a certain genre, and then, boom, he twists something. Just when you feel, okay, I get this, I know what’s happening here, he turns something around.

Fallenberg: They’re “genre-bending.” For example, one of the plays we’ve just finished working on called The Lamenters—it’s a tragedy, if you go by the classic definition, but it’s also quite funny. It has a lot to do with the staging and the actors, but also because that is what Levin intended.

Levin is very good, in the way of great literature, at taking something specific, which is typically Israeli, and then making it universal.

Weizman: What is it about Levin’s dramas that strikes such a strong chord with Israeli audiences?

Fallenberg: They’re intriguing because they’re us. They are our less attractive aspects, our insides, our bodily functions, our stupid thoughts, our culture. Pickled herring shows up in almost every play we’ve done. There’s something Jewish, something Polish, something Middle Eastern about the plays. He’s very good, in the way of great literature, at taking something specific, which is typically Israeli, and then making it universal.

Cohen: A lot of people have said things like the reason he’s so successful in Poland is because he’s really a Polish playwright. But what to me seems so Israeli about his plays is this incredible blend of seriousness and dismissiveness. Often the types of conversations I have with people here, the reason that I enjoy talking to people when I visit the country, is because you can find yourself speaking with people about philosophy and capitalism and democracy, these really big themes, and people are really serious and thoughtful about them, but then almost in the same breath, someone will make some comment about how stupid everything is, or start talking about food, and it’s all there, all at the same time. That’s how people’s minds really work, except in more refined cultures we’ve learned how to divert the way we talk and the things that we talk about into what is appropriate for the setting and the context and the crowd. But Israelis aren’t like that.

Fallenberg: In the West, speech is moving farther and farther away from thought.

Cohen: Exactly. For example, I could be talking about Kant, when suddenly this thought about pickled herring comes into my mind, and with Levin, that’s the thought that’s going to come out in his dialogue. In Walkers in the Dark, he embodies that idea in the actual characters; for example, you have, “The thought about pickled herring” or “The thought about”—what was it?

Fallenberg: Pyramids.

Cohen: Exactly. These thought-characters are all over the place, not communicating with one another, and somehow it all comes together.

Weizman: What are the particular challenges of translating Levin’s work?

Cohen: For me, this is the first time I’ve ever translated theater, and I’m finding that the emphases are different from translating fiction. One of the problems that comes to mind is that of names. Levin’s names are unique, often full of double meanings to a Hebrew speaker, so we had to think about how they would sound to English speakers—how to keep, where possible, a hint of those double meanings. The sounds are like Pupchik and Kupchik, which just aren’t meaningful in English.

Fallenberg: They still sound funny.

Weizman: But they’re also more difficult to pronounce. Those sounds don’t roll off an English-speaking tongue in the same way.

Fallenberg: I just learned from a Polish translator that the name Dupa actually means “stupid head” in Polish, and then I started worrying, what did we miss? But then I realized that most Israeli audiences wouldn’t have known that either, and luckily, Dupa sounds funny.

The language can be at one moment biblical and rich and then the next ridiculous, absurd, and scatological.

Another challenge that occurs to me is Levin’s ridiculous little rhymes. We had to decide what we would retain. For example, in The Thin Soldier, there is a little song, and we wanted to keep the rhyme scheme and meter, but it also tells a story, about a mother fly and her “flychick.” We had to retain the story because it has resonance for the play itself. But those sorts of challenges, where we would look at it and say, “We’ll leave this for later,” were rare. I find that his plays are characterized by language that is both high and low. The language can be at one moment biblical and rich and then the next ridiculous, absurd, and scatological, so we get to these situations where in the middle of this high dialogue we would have to say, wait—is this balls and prick? There’s a whole passage about nipples, an ode to the nipple. So the challenge is how to work that in.

Cohen: I actually come across that sort of thing a lot in Hebrew. It’s extreme with Levin, but contemporary Hebrew literature swings between high and low registers, between biblical and colloquial, all the time. In Grossman I had that, and in many other writers.

Weizman: Levin’s characters are firmly rooted in Eastern European Jewish social culture. To what extent did you attempt to preserve that aspect? How did you manage to convey that culture to people who don’t know it?

Fallenberg: These are plays, and so the challenge is very different from narrative. All we have to work with is what the actors say to one another. There’s much less leeway. One time we were trying to choose one of five possible English words for something in Hebrew. As we often do, we were arguing it this way and that, and suddenly I said, “I think this verb also has a political nuance, and maybe that’s what he meant in the Hebrew,” and Jessica agreed with me. But that’s as far afield as we can go. Our choices are prescribed by the words these people say to one another. There may be more leeway in the stage directions, but that’s less significant.

Cohen: It’s the same challenge as getting across any aspect of Israeli culture to someone who doesn’t know it. Israeli culture has a lot of Eastern European influences in it, and also a lot of Middle Eastern and Mediterranean aspects—though those don’t show up as much in Levin’s work. But that’s the challenge of any translation when you’re going from one culture to another—getting across things that people don’t even know exist.

Weizman: Can you give an example or two of instances where you had to deliberate?

Fallenberg: Sometimes when we encounter something very subtle, something with hidden meanings—we have to be careful. We’re translating someone whom many consider to be the greatest Israeli playwright of all time. That’s a big deliberation right there. As soon as you start you think, What if I get something wrong? Everyone is going to be looking at this and everyone is going to be critical. There are people who knew him, people who directed his plays and acted in them. Who are we? Both of us have felt from the beginning that we’re very grateful to have each other to do this with. There are so many little pitfalls, nuances of language, nuances of meaning, little inside jokes or references that we may not be completely aware of.

In Walkers in the Dark, for example, one of the characters is a French student, and she’s supposed to represent Paris and Parisian culture, and in particular, what Israelis of the 1970s would have thought about the haute culture that didn’t exist here and for which some Israelis were pining. You have to know those things, and it can be daunting. They give cause for reticence and respect. Both of us, in our translating careers, have had the privilege of working with really fine writers who know what they’re doing and are worth spending time with, but this is maybe a special case. Sometimes it has to go slower.

As part of our process we initially met with the aim of checking whether this co-translating thing was going to work. We spent a day or two translating test passages, to feel out how we would work together. And Jessica said to me, you know, I could do this so much faster on my own, but I actually like the results that are coming out of it because we can discuss so many things that arise. Of course you normally have these little dialogues with yourself as you translate—they’re so brief and immediate that you don’t even notice you’re having them. But when you have to voice them and you have to convince someone else, or be convinced by someone else, and you come to see that your opinion was not the best option, or recognize a new level that you didn’t realize was there, it adds a new richness to the quality of the play.

Cohen: There are things that we found in almost every play. We would be translating a line of dialogue, and Evan would instinctively use one specific word and I would instinctively use a different word. Now we’re aware of each other’s preferences, but to begin with—

Fallenberg: Or to start with—that’s one of them.

Cohen: (laughs) Right. It never would have occurred to me to say anything other than He starts to walk, but now I know that Evan wants the character to begin to walk. There are things that seem very minor. When I’m translating with myself in my own mind and there’s no one else interfering, I don’t stop to think, Could there be a different way to say this? It’s just obvious to me that this is how you say it. But when Evan and I work on a translation together, it’s like there’s constantly another brain challenging your instinctive choices.

When Evan and I work on a translation together, it’s like there’s constantly another brain challenging your instinctive choices.

Weizman: Translating is difficult enough alone, but you’ve had to find a way to approach this challenge together. How did you go about it?

Cohen: I was initially approached to do these translations, but I felt that I didn’t have enough affinity with theater to take them on. I felt that Evan would be better at it, and I asked if he wanted to do it, and he came back with, Let’s do it together. At first I rejected the idea. There’s a reason that I’m a translator; I sit alone all day with my computer and that’s how I like it. But somehow Evan convinced me to try it. I was pretty skeptical about how it was going to work. I thought we’ll either manage to do this, but we won’t like each other anymore, or the translation won’t work well. But I was completely wrong on all counts. I think we argue well. It’s not that we don’t argue sometimes, but we disagree in a productive way. I’ve never come away thinking I gave in to him on some particular point.

Fallenberg: I tell my translating students that the very best of literary translators are writers themselves. That’s why I insist that they also study creative writing. I’ve always seen Jessica to be an exception, and then one day it dawned on me, Jessica is simply a writer who chooses to use her writerly talents to translate other texts.

Cohen: (laughs) Going back to what I was saying, translation is a solitary profession, but I now realize how fruitful it is to come out of that mind-set sometimes, to be forced to do things slightly differently, to challenge your set thinking patterns. When you take on something like this it shakes things up a bit.

Fallenberg: We insisted on being able to meet in order to work together on each play. I’m based here, and Jessica lives in the US, and even though it would have made sense technically for us to divide up the work and then compare what we did, or decide that one of us would translate and the other would edit, we felt that the translation would be most successful if we worked on every word together. We decided that we would both first read the play on our own and then meet in order to do the work. When we get together to work on a play, we’re both looking at the original text, but one of us will speak out the translation while the other types it up. It’s almost like taking dictation, except that the person who’s typing will interrupt if there’s something they want to do differently, in which case we discuss our options.

Cohen: After we finish that first draft we switch—the person who typed reads the new English text aloud and the other follows along with the Hebrew.

Fallenberg: At a later stage we consider all the other elements—italics, bolding, stage directions. And then we watch the play, to see what we’re missing. We try to get versions that were directed by Levin himself, so as to get as close as possible to what he intended in the text.

Once or twice we’ve consulted other people who worked with Levin to get clarifications. And then, a month or two later, we read it again and make final changes.

Cohen: I do that with prose as well. In the very last stages I read everything out loud, because when you hear something spoken you catch things you don’t see on a page. With a play, that’s even more important. That’s all there is—how it sounds. For example, you can be reading and see that you’ve used the word “mourning,” but when you read it you’re hearing “morning.”

Fallenberg: Sometimes you have exactly the right word, but you can’t use it—it’s fine on the page, but on the stage it will be confusing.

Weizman: What is most difficult about co-translating? What are the advantages? Would you say it ultimately produces a stronger translation of a work?

Fallenberg: I wouldn’t say that that’s true for every co-translation. But in this case, we’re two seasoned translators, so it’s safe to say that because of the way we work, the way we hold each other to a standard, and the way that our process managed to break down our personal language patterns, for all those reasons, it’s a better text.

Cohen: As far as I know, most co-translations are of poetry, and very often one person is fluent in the source language but not in the target language, which is really not the case with us. This is something very different.

Fallenberg: There’s something very satisfying and enriching about working this way. It isn’t the most productive method, but for this project, we made a point of carving out chunks of time to give to this. The Institute of Israeli Drama made it possible for us to work this way, and for me, it was a lovely break. Like a rare opportunity to climb into somebody else’s brain.

Weizman: Do you know of any productions that are forthcoming, now that English speakers will have access to Levin’s work?

Fallenberg: An anthology of twelve of Levin’s plays in two volumes is coming out later in the year from London’s Oberon Books, containing our translations as well as several others translated by Naaman Tammuz. The plays will be represented by Judy Daish Associates. Hopefully, new directors and producers will have a chance to enjoy his work and take them on.

Also, in July, at the international cultural institute Mishkenot Sha’ananim in Jerusalem, we’re holding a special translation residency on the work of Levin, at which we’ll be hosting translators from all over the world—some of his finest translators and also people who have not yet translated him.

Most of the plays have already been vetted, and people are very pleased with them. That was great to hear—that people who are involved in Levin’s work have given their approval. We have a strong feeling that something worked well here, in this collaborative process, so it’s wonderful to hear from others in the know about his work and about theater that we’ve gotten it right.

January 2019

Jessica Cohen was born in England, raised in Israel, and lives in Denver. She translates contemporary Israeli prose, poetry, and other creative work. She shared the 2017 Man Booker International Prize with David Grossman for her translation of A Horse Walks into a Bar. She is a past board member of the American Literary Translators Association and has served as a judge for the National Translation Award.

Jessica Cohen was born in England, raised in Israel, and lives in Denver. She translates contemporary Israeli prose, poetry, and other creative work. She shared the 2017 Man Booker International Prize with David Grossman for her translation of A Horse Walks into a Bar. She is a past board member of the American Literary Translators Association and has served as a judge for the National Translation Award.

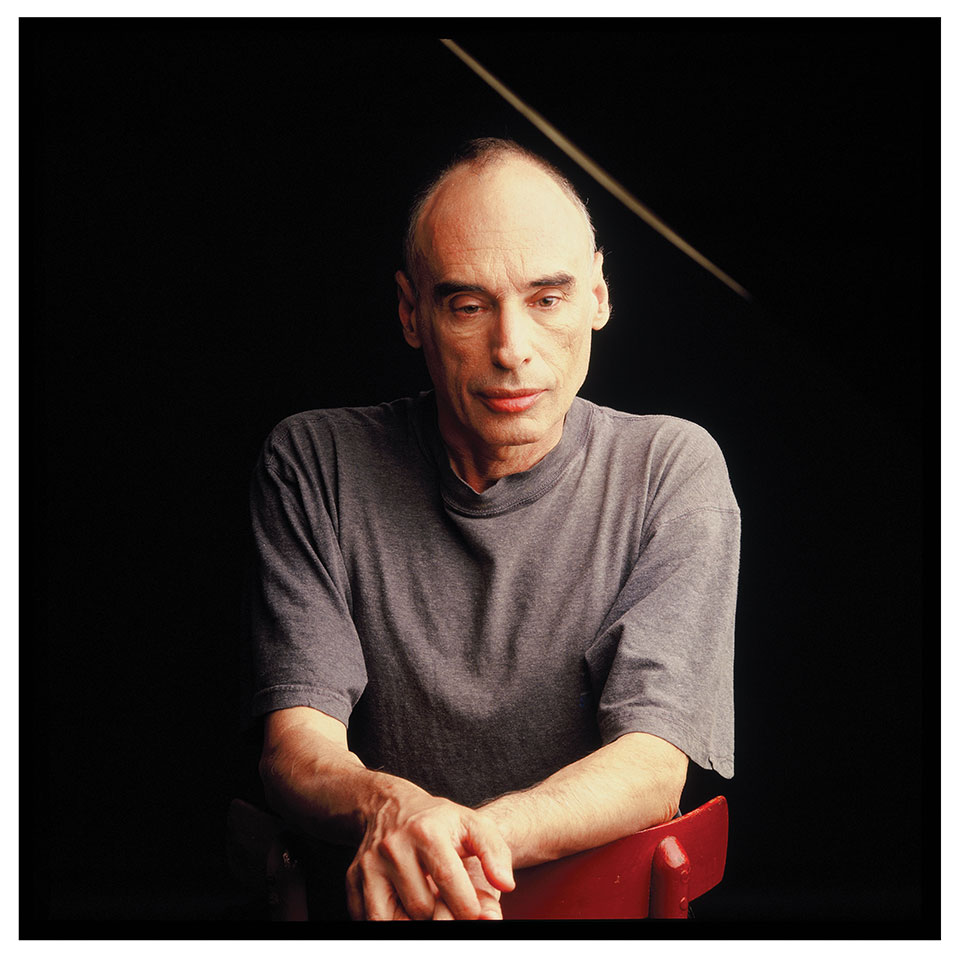

Evan Fallenberg’s most recent translation is a new Israeli opera, The Sleeping Thousand. His third novel, The Parting Gift, was published by Other Press in 2018. He teaches at Bar-Ilan University and is faculty co-director of the International MFA in Creative Writing & Literary Translation at Vermont College of Fine Arts.

Evan Fallenberg’s most recent translation is a new Israeli opera, The Sleeping Thousand. His third novel, The Parting Gift, was published by Other Press in 2018. He teaches at Bar-Ilan University and is faculty co-director of the International MFA in Creative Writing & Literary Translation at Vermont College of Fine Arts.