The Signorina Rubí

A woman’s writing, and routine, are disrupted when she meets a man on a bicycle.

The signorina Maddalena Rubí has a passion for poetry.

She writes a little after dinner each night, before going to bed. After tidying up the kitchen she moves to the living room, where a Toshiba 702 laptop waits for her on a small walnut writing desk beside the window. She opens it and, with light pressure from the forefinger of her left hand, turns it on, starts Word, and begins to type.

A long time ago, before this technology existed, she’d draft by hand on thin, semitransparent sheets, the kind once used as tracing paper; then she’d type up a final version and pin it to her other works, keeping them together like a little book.

One day a substitute teacher told her that her surname, so musical and graceful, could have escaped from a crepuscular poem and loaned her a small volume by Guido Gozzano.

She’d started this when she was a student at secondary school. Everyone in her class, tutors and peers alike, called her Rubí. One day a substitute teacher told her that her surname, so musical and graceful, could have escaped from a crepuscular poem and loaned her a small volume by Guido Gozzano. Intrigued, she read and reread it until she leapt into the verse by means of a simple substitution:

I remember. Her voice,

which could barely be heard

through tight lips:

“Oh Guido! What have I done

Has Rubí hurt you?”

She now enjoys that everyone at work calls her Rubí, and since she doesn’t have close friends or relatives to remind her that she is also Maddalena, she’s almost forgotten her full name. She even signs her poems Rubí, in pen, with the acute accent fleeing away from the í, like a plume of smoke from a chimney.

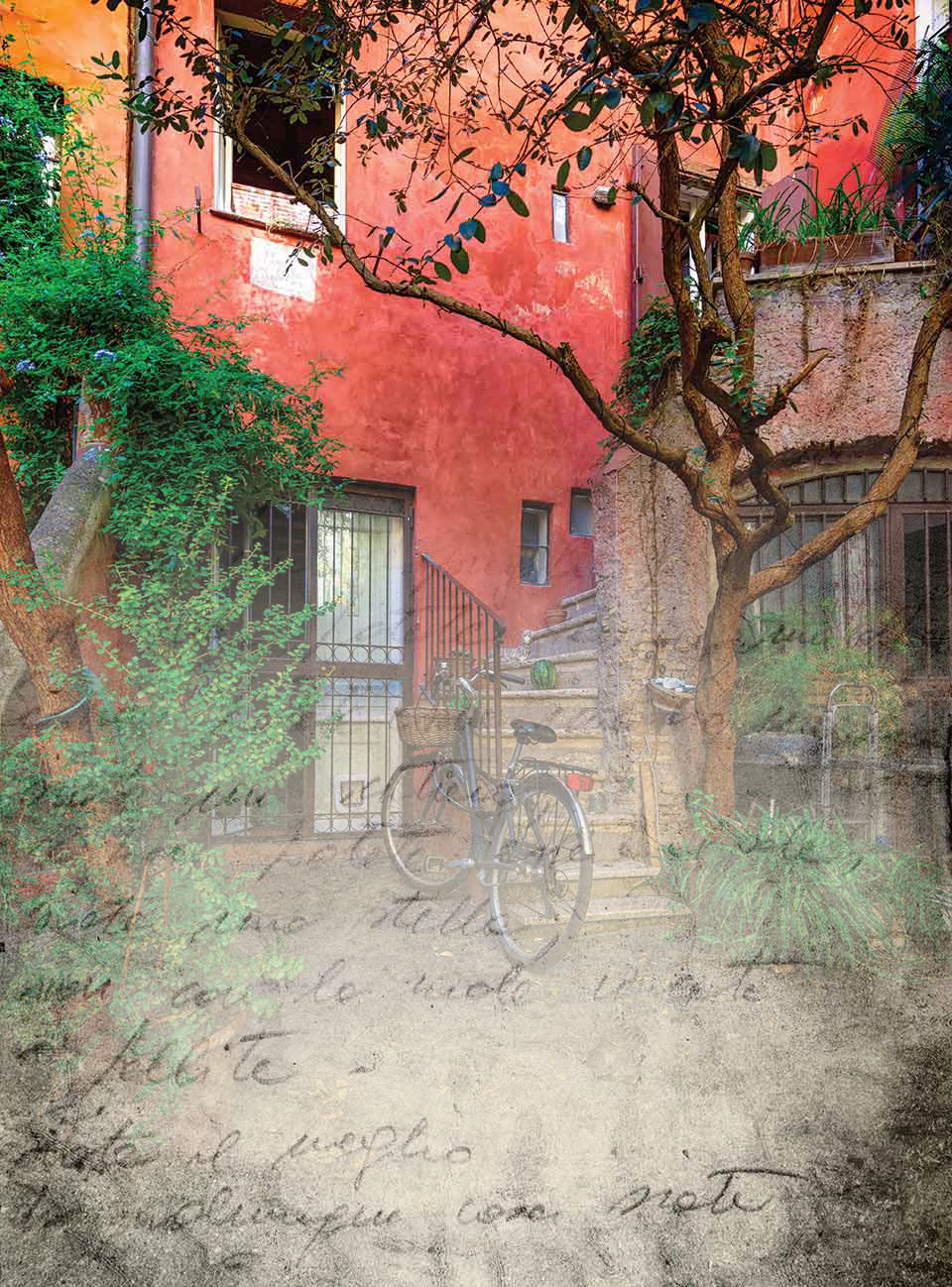

She was born in Sulmona, but now she lives in Rome, in a large building near the university that was built before the war to house railway workers. One Sunday morning, walking through the neighborhood in search of for sale signs, she’d stopped in front of a very tall gate, and above that gate, painted in yellow letters on ochre in all capitals, was the phrase semper splendet artis sol. It seemed at the time like an omen, and indeed she’s never regretted her decision.

On weekdays there’s a lot of commotion: students walking or on motorbikes, soldiers from Castro Pretorio, nurses, doctors, and ambulances from the nearby hospital. Yet beyond the gate and the lobby, the six-story construction surrounds a large courtyard that is filled with trees and bushes, and where, almost miraculously, no noises from outside reach, so it seems of another world, another time. For this reason, most of all, she grew fond of her apartment. Every now and then she makes a small alteration: she’s repainted the walls, changed the tiles in the bathroom, and varnished the shutters. But she does one thing at a time, without rushing, partly because builders and materials cost a lot of money, but also because she doesn’t like to disturb the rhythm of her life by having dirt and noise in the house. Besides, she doesn’t want her inspiration to be lost in the mayhem of the work.

She’s employed by the ministry, which isn’t far away. That’s why, twice a day, she can be seen coming and going on foot, in summer and winter, rain or shine. She returns between five and six every weekday. She opens the gate, passes through the lobby, and crosses the courtyard. She says hello to the people she meets and smiles, though she only knows most of them by sight. Arriving at stairwell C she calls for the elevator, which comes down and then goes back up, creaking in the metal cage, to the fourth floor. Here there’s a dark wooden door with a brass oval plaque on which her name is engraved. She inserts the key, turns it four times, then goes inside and switches on the light in the small entrance hall. She does this because, coming from the landing, she can’t see a thing. Then, immediately after taking off her coat or putting down her umbrella or bag, she turns it off. She always has so much to do before dinner that she doesn’t have time to feel alone.

She can’t bear the thought that on the other side of the courtyard, from the opposite apartments, someone might watch her at home and perhaps see her going about her routine.

She never opens her windows, except in the morning before leaving, to air out the rooms. She can’t bear the thought that on the other side of the courtyard, from the opposite apartments, someone might watch her at home and perhaps see her going about her routine. So, she keeps the shutters half-closed and leaves the house in semidarkness. By now she’s used to moving in dim light. Often, though, she stops what she’s doing and positions herself at the window to look outside without being seen. She doesn’t spy on other peoples’ lives, goodness no! She looks at the garden at the center of the courtyard, which is like a little forest, filled with trees and bushes, planted somewhat haphazardly and now growing on top of one another. There are three palms and two Lebanon cedars, two sycamores, oleanders, viburnum, and laurel. Some space has been left around the outside for the roses:

At this hour

Evening descends on the old garden

Of your home . . .

She feels the need to look at the garden every now and then, just as someone who’s thirsty must drink. She stops and goes to the window. The mass of trees and those tangled branches cheer her spirits, though she can’t say why. In the evenings, when she writes, if a rhyme eludes her she leaves the computer and goes to the window where, behind the shutters, she peers at the plants for a long time, even if it’s dark. She stays there until she finds the word that chimes with the sound.

It’s made of music, her poetry, and is concerned with everyday things. She works and works at it, almost every evening. And every time she rereads, she makes cuts, changes words, and moves them around. Sometimes a verse flows out, already perfect. More often it’s jammed and there’s nothing to do but delete it all and start again from the beginning. She knows what she wants, and she’s not easily satisfied. Whether to tell a story or capture an emotion, the tone must be clear and colloquial, the phrasing melodic and self-contained. A clear vision: everything given with immediacy and simplicity. She detests forced syntax, the naked word, loose, dissonant. She despises unrhymed verse or verses that are not verses, where the phrase is broken, detached from the line, and words thrown down on the page as if by a roll of the dice.

Because she wants to avoid constraints, she doesn’t write to get published. When she writes, she does so for herself, with no thought for the reader. She has little concern for literary trends, the hope of success, or the fear of being criticized. She wants to express herself freely, the way she feels. But she still has her models, the same ones as ever, and she learns from them. Sometimes she finds herself fantasizing that her compositions might be read by chance by someone who is so impressed that she hands them on to another person in the industry, a critic or a literary agent, and then, from there, on to another person still, to a publisher who knows nothing about the author, and so she searches for her . . . but she also likes the idea that her works might be found in a box after her death and published posthumously. They would discover she’d been years ahead of her time, that her style was more modern, far exceeding the poetics of her contemporaries, already in the future, because what was happening in the present? Honestly, very little.

The same dream as ever:

to live in a solitary house

without a past, without regret

doing what’s true to me, musing . . .

She says it out loud, repeats it. She’s content with herself and with her life: I’m happy. My life . . . it’s what I’d always dreamed of . . .

But this was months ago, not anymore. Something has changed. Her life is suffering, and her writing even more so. What happened? how? when? She asks herself this while standing at the window, behind the shutters, staring at the dark trees, the computer switched off. Her last poem was finished a year ago. After that only words, stumps of verse, a small stanza, and all around the space of the empty page. She often turns on the computer but doesn’t write. Then she switches it off again. On the screen she’s asked: Do you want to save? And she saves it just like that, lost in thought, all of that bright, white space.

She met him in the street, while she was coming home from work. On his bike, like always, with the rucksack on his shoulders. Many times before she’d watched him enter the courtyard and head toward stairwell A, on the other side of the garden. On more than one occasion she’d caught a glimpse of him looking out from an opposite window, on the third floor. Always, though, she’d pulled back as if he too could see her standing there, hidden behind the shutters. She’d wondered what job he had, whether he lived alone. How he would look without a beard. She’d found herself thinking about him against her will and had given him a name. In truth she’d even dreamt about him, but a strange dream: he was emerging from a hole in the ground and laughing, watching her and laughing as if ready to burst. In the dream she watched him, sad and slightly stunned, unable to understand.

Then she meets him. He’s mounted his bicycle on the pavement. He’s hit her, just a little. She isn’t hurt. But he’s fallen to avoid her, so she helps him back up, embarrassed, asks him if he’s injured. He smiles and shakes his head, looking at his hands. They pick up the books scattered on the ground. She hands them to him. He puts them in his rucksack, apologizes. It’s his fault, he says:

There’s barely a scratch.

Yes, but I frightened you, I’m sorry.

No, don’t worry about it.

May I accompany you?

We’re going in the same direction.

Really? To number 22? I’ve never seen you before. Shall we go?

We’re almost there.

That’s when she knew. How much? So much. And all at once. More than she’d ever hoped.

Adamo Ferretti, nice to meet you.

I teach literature, yes, here at the liceo. Italian and Latin.

It’s strange I’ve never seen you before.

At the ministry? And do you like it?

I also worked at the university.

No, only research. On a contract. Terrible pay.

I enjoyed it but . . .

I published too. In journals. Several times.

I live alone. Renting.

It’s just my mother left, in Grosseto.

Goodbye.

Goodbye then.

The bicycle is there every evening, tied to a lamppost. Rubí returns home, sees to her things, makes dinner. Then she goes to the living room and writes. She writes about the youth that passed her by: perhaps she was beautiful and never knew. She writes about her days: the job she does not love, a few phone calls, the newspaper, always the same, the television on. She writes about her fear of death, even though it’s soon, still too soon, to fear dying alone. She writes about what she has never had. What she has not yet had.

Which poet?

Gozzano? Oh, come on! Really? In this day and age? Gozzano?

That’s organ-grinder music. You never hear it anymore.

Musty old stuff.

She writes. She used to detest the unspoken, the unfinished, forced syntax, words that are symbols of who knows what. Now, she tries it. For the first time she feels behind. She feels the impulse to change, to change everything. What’s to lose? She tries. But she isn’t satisfied. She casts a rhyme aside and it reappears on the next line. She tries to dig little trenches between one word and the next.

In the mornings she goes to the ministry, as always. Sometimes she meets him and says hello. A few words: have a good day, everything’s fine, thanks.

Time stands still. Inside it’s stifling. Instead of working, she thinks. She thinks that she’s wrong not to open herself up. Not to let herself be known. That she’s throwing her life away behind the bureau. That there’s only one life. One life.

In the evenings too, when she’s returning home, she sometimes meets him. It’s October. A beautiful, clear, cool October in Rome. He steps down from his bicycle and they walk together chatting. She answers.

The job at the ministry? It’s tolerable.

Only a brother in Sulmona who’s married and has two daughters.

Do they look like me? Yes, perhaps.

The holidays there. Yes, always.

For a long time by now.

I live alone here.

Yes, quite alone.

How suddenly everything changes. Sitting at her desk, she’s taken over by the fear that she won’t manage to follow the trail of this new inspiration. She incessantly gets up and goes to the kitchen to drink, then takes a seat, stands up again, paces up and down the room. The rhymes escape in a torrent, out of control. Chiave, grave, fave, nave, bave, cave . . . Viva, stiva, piva, riva . . . Adamo, chiamo, ramo, amo . . . She sends them away, almost ashamed. Anyway, she doesn’t need them anymore.

In the mornings she goes out a little earlier and walks more slowly. In the evenings she stops to look in the shopwindows. She doesn’t wait for him, only hopes. Sometimes they meet. It’s fully autumn. The leaves of the sycamore are falling. They’ve pruned the oleanders, viburnum, palms, and roses. If it rains he leaves his bicycle behind. That’s when it happens.

No, it’s not cold. Despite the rain.

Are you going home?

What are you reading?

Yes, but I didn’t like it.

What do you mean? You don’t know it?

At the cinema near here.

Why don’t we go together?

How slowly, slowly everything changes. For some time now, instead of going straight home, Rubí has been circling the streets around her building. She walks, and while she walks, she looks at the traffic of cars and people. She reads the graffiti on the walls, the signs and the posters. She’s amazed: how many words! Everywhere. More words than things, maybe. Impossible to say how many.

She’s astonished that anyone could move like that and depart, without hesitation, without fear.

One evening she goes as far as the station. She enters into the chaos of hurrying people, amidst the roar of the loudspeakers and the moving trains. How many people setting off, and with such courage. She’s astonished that anyone could move like that and depart, without hesitation, without fear.

What a surprise! It’s a long time since we’ve seen each other! How are you?

Have you seen this traffic?

I’ve been working, reviews, articles. And then school.

And an essay.

Are you going home? What would you say to a stroll?

Do you really refer to yourself as Rubí?

If you don’t mind, I will keep calling you Maddalena.

It’s almost Christmas already. It gets dark early. She went back to the station, more than once. One evening, on a platform, sitting on a marble bench, she cried. She won’t leave, she won’t go to Sulmona. She feels a little bad, for her brother, for her nieces. Not for her sister-in-law. She’s decided to stay. Yes, to stay. Everything is different, yet everything is the same. Nothing ever changes. Or perhaps not. Just wait. Just take the risk.

It’s my pleasure.

Oh, it’s big in here. I’ve only got one room.

Perhaps I should leave it. The rent is expensive.

This is delicious!

You’ve worked a lot. You shouldn’t have. For me.

Do you like the wine?

What about your hair? You were so pretty with long hair.

Sorry, you look good like this too. It’s just that I was used to it.

Yes, I don’t have many friends. Only colleagues.

Women? No, I would tell you.

And you?

Really?

I don’t believe it!

She doesn’t know what’s going on. She thinks it’s her fault, that she doesn’t know how to offer what she’s never had before. Perhaps she cannot communicate. She doesn’t write anymore. The cedars, viburnum, and laurel are greener, the sycamores have new leaves, and the roses are in flower. The bicycle is tied to the lamppost like always. Even if she tries to read, she’s too tired. She’s overwhelmed by an anxiety to say, to do what? To move, get up, go out. Just wait, have a little patience.

I’m going back to Grosseto.

No, I don’t want to, but I have to.

I wanted to tell you, but I haven’t seen you around.

Email. Of course. And my number.

I’ll come and see you when I’m in Rome.

The August bank holiday’s over, and Rome is deserted. Outside it’s raining. Rubí sits at the desk, turns on her computer, and opens a new file. She begins. Just type. One letter after another. A line of words. Enter. A new line. Enter. And so on until the end.

She writes and writes. The words become conjoined, yielding to the rhythm of the idea. A simple melody, but only on the surface. There’s work behind it. Nimbleness. Spontaneity. And passion too. But this isn’t a cry. More like a lament. That’s it: an elegy. Because there’s no despair, only melancholy. This life of dreams, sterile. Better the coarse and cruel life? What should she do? Living, alive. There’s no way. To leave behind these identical days. Enough exile. But perhaps time is already stronger than all her courage. She writes. Never. The rhymes had never come to her more easily.

Never an inspiration so precise. So new.

Translation from the Italian