China’s Battlers Poetry: Punching Up

China’s “Battlers poetry” is written by members of the new precariat, especially rural-to-urban migrant workers. This is an exciting trend, both in its own right and when viewed as part of a more widely reported sense of poetry’s revival in the twenty-first century.

For a while now, there’s been talk of a poetry revival. Maybe we need not take this any more seriously than recurring claims of the death of poetry, or its irrelevance in a demystified and disillusioned world. If you don’t buy it when they say poetry has died, you can’t very well rejoice when they say it’s come back alive. But something is going on. It flows from poetry’s ability to be at once ancient and cutting-edge, and to speak to social realities at the same time as transcending them.

Three examples, from my personal perspective. One: in Dutch poetry, inasmuch as I “naturally” know about this as a native speaker who takes an interest, there is growing engagement with issues of social justice, from racism to environmental destruction and surveillance capitalism. This poetry wants to assert itself in society rather than shield itself from society, without the awkwardness vis-à-vis the mundane that can mark the genre in its more rarified moments.

Two: in international scholarship, one encounters theoretically armed-to-the-teeth, transnational projects on poetry in the twenty-first century. These projects often invoke globalization, new media, and liberation from strictures of social class and poetic form (think spoken-word, Instapoetry), and they question the notion of aesthetic value as inversely proportional to the size of the audience.

Three: in Chinese poetry, my area of specialization, there’s the fascinating phenomenon of poetry written by members of China’s new precariat, mostly rural-to-urban migrants whose cheap labor has fueled the workshop of the world since the 1980s, with few civil rights and often under gruesome conditions. There are about three hundred million of them, and many have put pen to paper—or finger to touchscreen, as smartphones have enabled the emergence of an imagined community-in-poetry over the last fifteen years or so.

In English, their writing is usually referred to as migrant worker poetry. Nothing wrong with that, but it is an explanation rather than a translation. I prefer to call it Battlers poetry instead, after an Australian colloquialism. This comes closest to the Chinese term (dagong shige), which breathes a mix of denigration and pride, of vulnerability and strength. Battlers writing is now becoming visible outside China, in poetry and other genres such as autobiographical fiction, in the work of authors like Zheng Xiaoqiong, Xu Lizhi, Fan Yusu, and others who appear in these pages.

Similar trends exist elsewhere in the world (for comparison, in one of my classes we look at poetry by Latinx immigrants in the contemporary US). Still, Battlers poetry is a very Chinese thing. Punching up from the grassroots, it shows that in China, poetry is a social practice that crosses socioeconomic boundaries. It also highlights the uneasy entanglement of low-skilled labor, literary writing, and the state in modern China. The battler’s ordeal—displacement, exploitation, alienation—is a far cry from jubilant images of the worker as dignified masters of their fate in the early, high-socialist decades of the People’s Republic. Accordingly, the literary establishment approaches this writing through a combination of sponsorship and censorship.

The literary establishment approaches this writing through a combination of sponsorship and censorship.

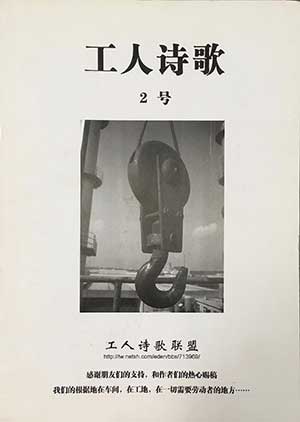

But things aren’t just black and white. Today’s state capitalism brings hardship and precariousness but also opportunity. Conversely, back in the day, high socialism brought jobs for life but also cynicism—and remembering this is one of the many things Battlers poetry can do. Witness this excerpt from Chen Ge’s “The State Factory,” published in the first issue of Workers Poetry (Gongren shige, 2007), a fine specimen of China’s formidable tradition of “unofficial” poetry journals:

Back then we worked at the state factory / with its tall walls and vast grounds / The socialist grass grew like mad / We’d often drop everything / and start cutting. That is to say / there’d be an investigation yet again / With higher-level leadership descending to inspect the guidance we were offered / By the looks of it they didn’t like / wild grass uncut . . . And we’d cut. And cut. And cut / Cut through the neck of slavery / Cut through the spine of feudalism / Cut off the tail of capitalism / We harvested socialist wild grass / and communist thought / We didn’t cast off our chains / and we didn’t win the world

This adds to the story of writing by the underclass, from another angle. And that is precisely what is needed as we engage with Battlers poetry as an illustration of the genre’s versatility, as above: at once ancient and cutting-edge. And punching up.

Leiden University