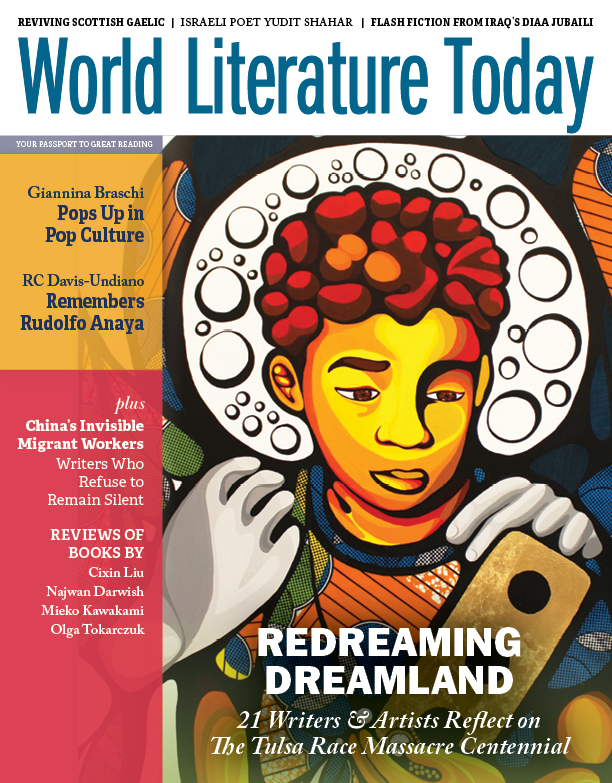

How We Write about Tulsa

Several recent works on the Tulsa Race Massacre add to an already rich collection of publications that serve as essential resources for learning the histories of our communities and how we can meaningfully honor those who have endured racial terror.

As the year 2021 begins and we mark one hundred years since the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre, a horrific attack on African American Tulsans that was meant to invoke terror and enforce white authority, many in Tulsa are reflecting on our city’s legacy of violence, ever mindful that the coming of this year shines a light on our community and its failures, even as we point toward evidence of triumph. As political, institutional, and community leaders mark the centennial with events, programs, and the completion of a new history museum, the story of the Tulsa Race Massacre and the eventual rebirth of the Greenwood District will be told and retold. And yet, even as our city has been shaped by this violence into the present, many Tulsans will stubbornly insist that the past should stay in its place. Still others will express surprise and sadness at learning about the Tulsa Race Massacre for the first time, confessing that “no one told them” about this profoundly traumatic event for our city and nation, though it is the subject of a now-comprehensive body of scholarship, literature, and journalism developed over decades. Centennial commemoration events long planned with great anticipation have unfortunately been dimmed by the Covid-19 pandemic, which itself exposes enduring racial inequities in Tulsa and worldwide. Coupled with the pandemic and following numerous egregious acts of police brutality against African Americans, an insurrection attempt at the US Capitol on January 6 of this year—fueled by white nationalism—echoed the acts of mob violence that continue to haunt Tulsa.

The important work of commemoration has been ongoing long before 2021 and our current challenges.

While it certainly is not news that silence has surrounded the events of 1921 for years in Oklahoma, including in school textbooks, the important work of commemoration has been ongoing long before 2021 and our current challenges. Due to the efforts of a broad coalition of leaders inspired by the memories and words of those who survived the massacre, institutions such as the Greenwood Cultural Center, the John Hope Franklin Center for Reconciliation, and the Tulsa Race Massacre Centennial Commission, among others, provide numerous opportunities for learning about and becoming involved in advocacy for truth and reconciliation in Tulsa. The centennial is an opportunity to ask ourselves key questions: When will we be responsible for learning the histories of our communities, even if “no one told us” these histories (or we weren’t listening)? How can we meaningfully honor those who have endured racial terror in our country and ensure that we do not perpetuate the kind of ignorance that led to their suffering? Who should tell the story of the Tulsa Race Massacre, and what if narratives of the massacre conflict? What should the future of Greenwood be?

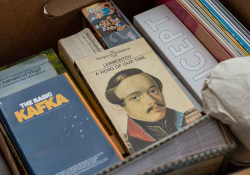

Several recent works on the Tulsa Race Massacre add to an already rich collection of publications that serve as essential resources for finding answers to these questions. Fiction, drama, poetry, memoir, eyewitness accounts, journalistic, photographic, and scholarly histories (and works that cross genres) comprise the full canon. Some literary works were completed in the massacre’s immediate aftermath by those who witnessed it. A poem, “A Request from a True Friend,” was composed by massacre survivor A. J. Newman in 1921 as a tribute to Red Cross relief director Maurice Willows, who himself compiled a report documenting the Red Cross’s efforts to provide “relief to the innocents.” A. J. Smitherman, Tulsa Star editor and key leader of African American resistance to racial violence in Oklahoma, published in a pamphlet in 1922 the poem “The Tulsa Race Riot and Massacre” after fleeing Tulsa for Massachusetts. A short story by former Tulsan Frances W. Prentice, “Oklahoma Race Riot,” was published in Scribner’s in 1931. Magic City (1997), by Jewell Parker Rhodes; Fire in Beulah (2001), by Rilla Askew; Dreamland Burning (2017), by Jennifer Latham; and Angel of Greenwood (2021), by Randi Pink, are all contemporary novels that feature the massacre within their plotlines. Clemonce Heard’s Tragic City (2021) explores the legacy of the massacre through poetry. Tara Watkins’s play Tulsa ’21: Black Wall Street (2018), Deborah Hunter’s Porches (2021), and Marta Reiman’s 2021 adaptation of Askew’s novel bring the story to the stage. Opal’s Greenwood Oasis (2021), a middle-grade children’s book authored by Quraysh Ali Lansana and Najah Amatullah Hylton and illustrated by Skip Hill, provides a tour of Greenwood on the eve of the massacre through the eyes of an eight-year-old. Adding to this creative treatment of the massacre are several film projects under development by production companies linked to such household names as LeBron James and Russell Westbrook, coming on the heels of Damon Lindelof’s choice of 1921 Tulsa as the setting for the 2019 premiere of his HBO series, Watchmen.

/ Courtesy of the Tulsa Historical Society and Museum

When will we be responsible for learning the histories of our communities, even if “no one told us” these histories?

Alongside the trajectory of creative renderings of the massacre are histories that likewise began with firsthand accounts and experiences of the violence that waged destruction on Greenwood in 1921. Mary E. Jones Parrish’s Race Riot 1921: Events of the Tulsa Disaster (1998) is a collection of eyewitness reporting from Parrish herself, a typing instructor and journalist who, having come to town from Rochester, New York, lured by the promise of opportunity in Tulsa’s Black economic ecosystem, was compelled to flee her home in the Greenwood District with her young daughter. Parrish not only includes her own detailed observations about the attack on her neighborhood but also compiles interviews with several other survivors; she self-published her book and distributed copies in 1922. Attorney B. C. Franklin, whose law office was destroyed in the massacre, completed a manuscript in 1931, “The Tulsa Race Riot and Three of Its Victims,” which was discovered in 2015 and donated to the collection of the new National Museum of African American History and Culture.

After decades of little attention devoted to telling the story of the massacre in the modern era, in 1971 Ed Wheeler published his article “Profile of a Race Riot” in Oklahoma Impact, a North Tulsa publication edited by state legislator Don Ross. Scott Ellsworth, arguably the foremost historian of the massacre, published in 1982 his dissertation, which was informed by oral histories of survivors, as Death in a Promised Land: The Tulsa Race Riot of 1921. Author and attorney Hannibal B. Johnson published Black Wall Street, which provided a history of Greenwood within a larger discussion of Oklahoma history, in 1998. The turn of the twenty-first century saw the arrival of several new books that accompanied the 2001 release of the final report of the Oklahoma Commission to Study the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921, with historian Danney Goble providing the report’s historical overview. Journalist Tim Madigan’s The Burning (2001), James S. Hirsch’s Riot and Remembrance: The Tulsa Race War and Its Legacy (2002), and Alfred Brophy’s Reconstructing the Dreamland: The Tulsa Riot of 1921: Race, Reparations, and Reconciliation (2003) were all no doubt galvanized by renewed attention to Tulsa’s past via the creation of the commission in 1997 following the massacre’s seventy-fifth anniversary.

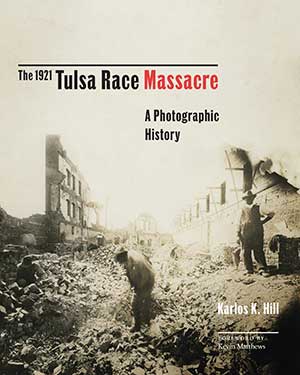

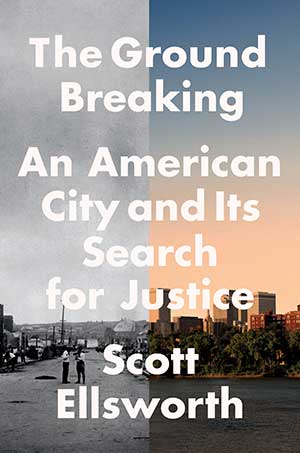

With the centennial, another critical mass of new writing about the Tulsa Race Massacre arrives, and with it some new developments in our reckoning with the truth and its role in our future. Randy Krehbiel’s Tulsa 1921: Reporting a Massacre (2019), Hannibal B. Johnson’s Black Wall Street 100: An American City Grapples with Its Historical Racial Trauma (2020), Scott Ellsworth’s The Ground Breaking: An American City and Its Search for Justice (2021), and Karlos Hill’s The 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre: A Photographic History (2021) all build on the insights of previous researchers while updating readers on the search for clarity and accountability regarding the massacre. Several subjects referenced in these works stand out as critical at the same time that they are debated. First, uncertainty about the number of lives lost and the presence of mass graves in Tulsa continue to complicate the legacy of the Race Riot Commission and relations between the city (specifically the mayor’s office) and advocates for Greenwood, including the survivors and descendants of the massacre. Second, there is an important conversation to be had about who writes about the massacre, whose narratives are given the most weight and exposure, and how stories of Greenwood impact North Tulsa’s future. Third, for many in our city, Greenwood is sacred, hallowed land, both because of the lives lost there and the promise of its thriving Black Wall Street. But the settler-colonial dynamics of Oklahoma’s history undergird tensions between African American and Indigenous Tulsans, notably over the status of the Freedmen but also in the discourse of land acknowledgments and “land back” advocacy that are a part of decolonizing movements. Finally, though actions to provide reparations to survivors stalled out after the commission report, there is renewed national dialogue about reparations that may factor into the case for such amends in Tulsa. These conversations accompany concerns about gentrification in Greenwood. Investment in a renewed Black Wall Street is often touted as a kind of reparation, but rising rents and contracts granted overwhelmingly to white developers call that assessment into question.

With the centennial, another critical mass of new writing about the Tulsa Race Massacre arrives, and with it some new developments in our reckoning with the truth and its role in our future. Randy Krehbiel’s Tulsa 1921: Reporting a Massacre (2019), Hannibal B. Johnson’s Black Wall Street 100: An American City Grapples with Its Historical Racial Trauma (2020), Scott Ellsworth’s The Ground Breaking: An American City and Its Search for Justice (2021), and Karlos Hill’s The 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre: A Photographic History (2021) all build on the insights of previous researchers while updating readers on the search for clarity and accountability regarding the massacre. Several subjects referenced in these works stand out as critical at the same time that they are debated. First, uncertainty about the number of lives lost and the presence of mass graves in Tulsa continue to complicate the legacy of the Race Riot Commission and relations between the city (specifically the mayor’s office) and advocates for Greenwood, including the survivors and descendants of the massacre. Second, there is an important conversation to be had about who writes about the massacre, whose narratives are given the most weight and exposure, and how stories of Greenwood impact North Tulsa’s future. Third, for many in our city, Greenwood is sacred, hallowed land, both because of the lives lost there and the promise of its thriving Black Wall Street. But the settler-colonial dynamics of Oklahoma’s history undergird tensions between African American and Indigenous Tulsans, notably over the status of the Freedmen but also in the discourse of land acknowledgments and “land back” advocacy that are a part of decolonizing movements. Finally, though actions to provide reparations to survivors stalled out after the commission report, there is renewed national dialogue about reparations that may factor into the case for such amends in Tulsa. These conversations accompany concerns about gentrification in Greenwood. Investment in a renewed Black Wall Street is often touted as a kind of reparation, but rising rents and contracts granted overwhelmingly to white developers call that assessment into question.

Krehbiel’s Tulsa 1921, a deep dive into Tulsa’s news reports about the massacre, is copiously detailed, providing specific information about the key actors whose decisions (and missteps) led Greenwood to ruin. While the failures of news reporting, especially the incendiary language published in the Tulsa Tribune, have been named as justification for discounting the local news at the time, Krehbiel makes the case in his comprehensive study of news archives that the cultural mind-set of the city and the corruption that fueled the failures of law enforcement can be accurately gleaned from those reports. Particularly interesting are Krehbiel’s descriptions of the civic (and decidedly less civic-oriented) activities that occupied Tulsans of the day. From the strong-arm tactics of fiercely nativist and anti-union vigilantes, on one hand, to the lax regulation of dance halls, speakeasies, and hotels where people of different races mingled, the tensions of nativist whites who were unhappy about the perceived moral failings of Greenwood regulars were already simmering in advance of the spring of 1921. Krehbiel includes with his citations of reports of the mob attack references to Parrish’s authoritative account, offering a full and reliable sense of the scale and trauma of the loss that resulted. Of the death toll, Krehbiel writes that “the fact remains and cannot be ignored: from Day One, whites and blacks alike believed more people died during the riot than were accounted for. The search continues still, with the city planning a new investigation into possible mass burial locations, but the truth remains as elusive now as it was then.”

Of the massacre’s aftermath, Krehbiel makes clear that most white Tulsans, even those viewed as moderates of the time (among them leaders of all the major downtown churches), blamed African Americans for this blight on Tulsa’s reputation and took little meaningful action to encourage or assist in the rebuilding of Greenwood. The Real Estate Exchange, for example, organized a campaign for Black resettlement elsewhere to pave the way for a new industrial area, introducing debates over development in the area that persist. In the final chapter, Krehbiel traces the establishment of the Race Riot Commission and its report, which he concludes ultimately accomplished little, and documents ways the commission shifted focus from documenting violence and making specific recommendations to account for it (including the possibility of reparations), to the more positive message of reconciliation and a physical site for commemoration. With far less funding than originally committed from the state, John Hope Franklin Reconciliation Park was the result.

Krehbiel ends his book with the significance of the work of the Tulsa Race Massacre Centennial Commission, especially in the aftermath of the 2012 Good Friday killings in North Tulsa and the officer-involved shootings of Eric Harris, Terence Crutcher, and Jeremy Lake. He points toward the significance of Senator James Lankford’s meeting with constituents in North Tulsa as a sign of hope for genuine reconciliation. In light of Lankford’s calling into question the legitimacy of the results of the 2020 presidential election, in which heightened African American voter turnout ushered in Biden’s presidency, is that hope misguided? For some members of the commission, Lankford’s position on the commission is in question, as the violent actions of insurrectionists on January 6 called to mind the violent mob of 1921 in Tulsa. Lankford wrote a letter of apology to Black Tulsans, and, citing the important work of reconciliation, Senator Kevin Matthews, commission chair, announced on January 25 that Lankford will remain.

Scott Ellsworth’s The Ground Breaking conveys with candor and considerable self-reflection the lengthy and painstaking work of documenting the Tulsa Race Massacre and searching for graves of its victims, achieved in community with survivors and their families and led by the belief that this atrocity spoken of so little in his hometown of Tulsa would form his career. Ellsworth includes absorbing stories of his encounters with white Tulsans in his youth who, some casually and some forcefully, maintained their commitment to segregation and behaved with disdain toward African Americans. This is especially true of Beryl Ford (whom Krehbiel also mentions), who in the late 1970s was president of the Tulsa County Historical Society. When Ellsworth met with Ford and asked him to view photographs of the “riot,” under the auspices of seeing how white rioters were dressed, Ford’s denial was immediate: “There weren’t any white rioters. . . . They were all Mexicans and Indians.” Realizing the futility of searching for candid stories of whites’ roles in the massacre, Ellsworth formed relationships with individuals such as W. D. Williams, John Hope Franklin (who would become a mentor and colleague), and others who opened up to him about the significance of the atrocity and allowed him to create an oral history archive that adds to the interviews Parrish immediately collected.

Scott Ellsworth’s The Ground Breaking conveys with candor and considerable self-reflection the lengthy and painstaking work of documenting the Tulsa Race Massacre and searching for graves of its victims, achieved in community with survivors and their families and led by the belief that this atrocity spoken of so little in his hometown of Tulsa would form his career. Ellsworth includes absorbing stories of his encounters with white Tulsans in his youth who, some casually and some forcefully, maintained their commitment to segregation and behaved with disdain toward African Americans. This is especially true of Beryl Ford (whom Krehbiel also mentions), who in the late 1970s was president of the Tulsa County Historical Society. When Ellsworth met with Ford and asked him to view photographs of the “riot,” under the auspices of seeing how white rioters were dressed, Ford’s denial was immediate: “There weren’t any white rioters. . . . They were all Mexicans and Indians.” Realizing the futility of searching for candid stories of whites’ roles in the massacre, Ellsworth formed relationships with individuals such as W. D. Williams, John Hope Franklin (who would become a mentor and colleague), and others who opened up to him about the significance of the atrocity and allowed him to create an oral history archive that adds to the interviews Parrish immediately collected.

In his discussion of the opportunity and challenge of serving on the Race Riot Commission, it is clear that Ellsworth is disappointed in the missed chance to award survivors and their families some form of direct reparation (other than the gold commemoration medal each of 118 survivors received in 2001). The differing backgrounds and goals of the members of the commission, as well as the national media attention they received, also led to some strife, since as Ellsworth notes, he and his historian colleagues were often summoned for interviews, leaving commissioner Eddie Faye Gates to ask, “When are the local people going to get to talk?” Entwined with his discussion of reparations is Ellsworth’s dedication to locating and identifying the massacre’s victims, including the possibility that they are buried in mass graves in one or more sites. Ellsworth echoes Krehbiel’s assertion that the number of deaths is unknown (and may never be), but in this task, the work of telling the stories of survivors comes together with honoring those who did not survive, and the weight of the commission’s findings years ago seems to rest on what the experts consulting on the digs with Mayor Bynum and the City of Tulsa find today. The culmination of the Oaklawn Cemetery dig was the discovery in October 2020 of eleven coffins that constitute a mass grave.

Current efforts to revive the case for reparations are informed in Ellsworth’s book by the often-overlooked history of Greenwood that came after the massacre. The story of Greenwood’s rebuilding is often lost in an emphasis on the area’s devastation in 1921 but is nonetheless inspiring—by some accounts the era that most exemplifies the spirit of Black Wall Street in its thriving economy. However, Ellsworth explains that post–World War II industrialization ushered in a new era of big retail that squeezed small, independent Black business owners, and with desegregation, African Americans were afforded new and sometimes cheaper shopping options than could be found in Greenwood. Urban renewal in Tulsa, which in the 1970s brought the construction of I-244 right through the heart of the neighborhood, cut off North Tulsa from new growth southward. With the development of projects affiliated with the Centennial Commission and new institutions in the 1990s, new advocacy for Greenwood emerges in the activism of Rev. Dr. Robert Turner and attorney Damario Solomon-Simmons, as Ellsworth describes. Solomon-Simmons, himself a descendant of Creek Freedmen, is using a strategy that was successful in state lawsuits against opioid companies; he is suing the city of Tulsa and other defendants for reparations in light of the efforts of many institutions to profit off of tourism without compensating survivors and descendants of the massacre.

The search for, discovery, and excavation of mass graves gives legitimacy to Tulsa’s overdue effort to end the silence surrounding the massacre. In photographic form, Karlos Hill’s The 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre likewise expresses, in images, undeniable realities that witnesses have shared about the terror. Pairing images with excerpts from oral histories, chiefly those featured in Parrish’s book, Hill contextualizes photos taken by white Tulsans in the aftermath of the massacre within the broader history of American lynching photos. As Hill explains, these photos give “an unvarnished glimpse into the psychological underpinnings of white supremacist violence,” eliciting the enthusiasm of those who were eager to document their mob actions. Indeed, because of the racial terror it evoked, some, including John W. Franklin, son of John Hope Franklin, have assessed the events in Tulsa as a mass lynching rather than a massacre, akin to similar events in other cities in the early twentieth century when Ku Klux Klan activity was heightened. Hill also notes that no reparations to Black business owners were made following the massacre though some compensation was offered to white businesses, and like Krehbiel and Ellsworth, he views the results of the Race Riot Commission as falling short of potential.

Hannibal B. Johnson’s Black Wall Street 100 provides, of the recent literature, the most thorough accounting of the initiatives, institutions, and programs that have come into existence to commemorate the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre and effect meaningful change in Greenwood beyond the centennial. Johnson’s book details the members of the current Centennial Commission, outlines the purposes of the original Race Riot Commission, and includes written reflections from its members on the effectiveness of their work. Johnson’s book devotes considerable attention to the future of Greenwood based on Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s model of a “Beloved Community” grounded in justice, love, and equal opportunity. Johnson, acknowledging Tulsans’ struggle to live down our troubled past, calls on us to live up to our potential as embodied by King’s ideals. In Johnson’s view, the most meaningful action we as a community can take to move forward in achieving our potential is through education. Johnson’s design of a curriculum for teaching about the Tulsa Race Massacre thus appears in the appendix along with other educational materials.

Among our challenges is to remain open to new tellings, not just of survival but also of triumph against racism and hatred.

As we mark one hundred years since the Tulsa Race Massacre destroyed the lives of so many, we as a city and nation are aggrieved by acts of violence and performative power that are in many ways fundamental to our national story. In our telling of this story, we are hearing, witnessing, and honoring those who were victims of this violence. Among our challenges is to remain open to new tellings, not just of survival but also of triumph against racism and hatred. With the now numerous publications, media stories, and films about the massacre, let us never again rely on a “nobody told me” refrain to perpetuate the amnesia that has held our city back.

Tulsa, Oklahoma