The Storefronts Wore Their Names

Lord, he was born a pesky question. Know

he always wore the danger hour of dusk.

The white folks named his skin impossible.

He teetered, balanced on the Negro inch

of sidewalks, dressed in hues of chance and mud,

eyes straight ahead, while trying to recall

the gospels that were conjured just for him:

Unsee the white men that you see, demand

yourself upright. Your name is Rowland, give

it bellow. But in other mouths, that name

would slog through spittle, wrap its hateful hands

around his neck. He barely found the breath

to ask what was so terrible in him.

Their answer had to be some form of fire.

The answer’s bound to be some form of fire,

perhaps a blinding spew of blood, a tree

with shadowed arms that stiffen for the hang.

They sweat the need to disappear a thing,

to unbelieve in, unbecome a thing,

to call a man or boy a thing, to kill

all that he is until he’s less than that.

The white man loves to torch a thing,

to torch a landscape flat, to turn it to

mistake and then deny it ever was.

They hate by hating most the things

they’ve made to disappear, and then

what they still see—the way he walked, unleashed,

his stride, too loud, too Negro, riding flow

just like some Negroes stride, in overflow,

as if he were a man and white, he had

to realize how sharp the anger bloomed

inside their chests, and then—he touched the girl,

he ruined her sterling skin with his, they screeched

He touched the girl!, and if he did or not,

he did. And “touch,” of course, meant he

had scraped her with his crave, he bit

and lapped and penetrated, he drew blood

and moan, he left that nigger sound on her,

a wail she’d always wear. He touched her. So

his rawboned throat was measured for the noose,

and white men gathered for his disappear,

their tangled voices rising like a pyre.

Entitled voices tangled in a choir

of loathing, bloated blue, its keyless shard

of song a bitter spitting of his name

again and yet again—he’d shortened it

to Diamond Dick, and yes, they were afraid

that might be right, afraid Miss Sarah Page

would fret and fever-flail, not wanting to

forget him happening to her. They named

him beast, and startled at the way that he

succumbed to cuffing—upright, bristling,

knowing his people just enough to know

they wouldn’t let him swing, they wouldn’t let

him disappear, his body left to those

who’d sing their privilege in place of dirge.

They warbled privilege because their days

were filled with nothing but deciding how

best to dispose of Diamond Dick, his blunt

and brutish fingers still an awkward source

of agitation for Miss Sarah Page,

who some folks thought might not recover from

that touch, or what she’d dreamed as touch. But they

had no real knowledge of the family

of Negroes, viscous as the stubborn blood

of Negroes, men who’d lay their own lives down

so he could live. He sensed their rumbling march

toward him, determined men who knew the sun

rose high on every man, so every man

deserved some sun. The homes, the offices,

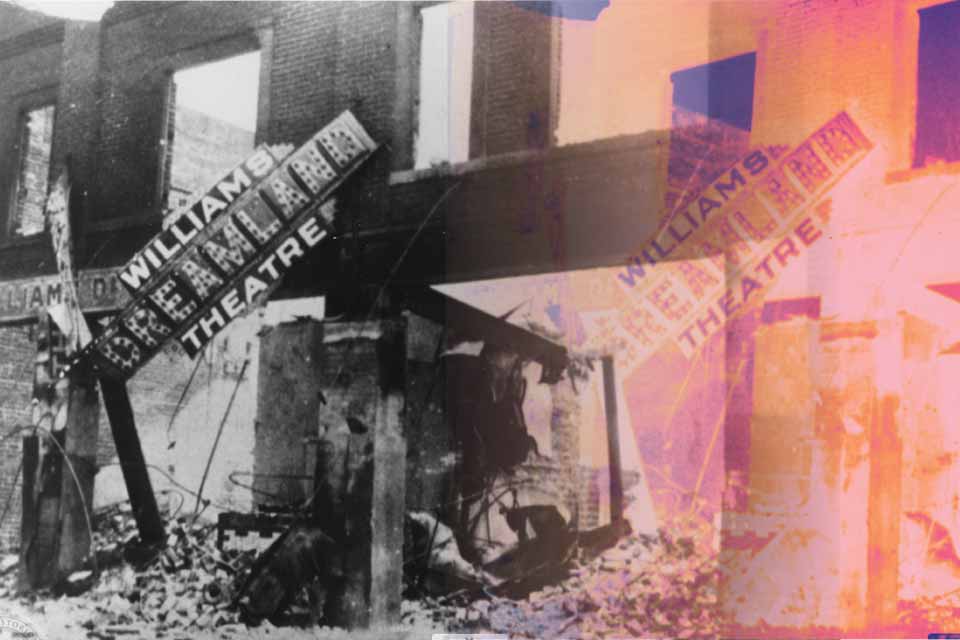

were theirs to own. The storefronts wore their names.

And yes, they’d gathered, minds set on that boy,

not knowing if their numbers were enough

to save him from the rope, but needing to

be there, to say, We’re here, to pull that boy

inside the widening circle of their arms,

to meet the menace in his jailers’ glare

with menace of their own. And as they marched

in their unsettled silence, hefting sticks

and guns, their path ahead began to swell

with rancor, venom blurred the way, and soon

those bladed sounds for black rained down, that spit

in lieu of Christian names. The crackling in

the crowd, the screech of hate and all its ways

aloud. The blacks clawed thru the toxic maze

of crowing, snarling throngs, that sea of white

the jail so close. And then—it could have been

most anything, so many things can make

“upstanding” men become the monsters that

they are—a numbing shove, a rifle wrenched

away, the flinging of a barb that names

a man much less than what he is, the gall

of those who will not lower their eyes or step

aside, so many things can make a man

decide on blood, to answer questions no

one’s asked with every form of fire. The boy

forgotten as that savage specter stalked

the Greenwood streets. White men, taking aim.

In Greenwood, so assured and laying claim

to everything a black man’s hands had built,

the chosen ones obliterated all

the crooked triumphs, those unscrupulous

successes, lives that coloreds had been fool

enough to think were theirs to flaunt and mark

with their tenacious stain. A fever, dank,

relentless just below the skin, had wrapped

the white men in its blister. So they were

inclined to kill it all, to blast the breath

even from things that never lived. Their howl

was feral, and their hatred blind. The god

in them set out to touch their sacred flame

to everything they set their eyes upon.

In everything he set his eyes upon—

the riddled bench, the wretched rusting bars—

the boy saw shudder. And the windows cried

of endings. He had touched a white girl—he

had grabbed her arm to keep from falling, but

had gone and really touched the girl—and now

the much-debated sacrifice of his

one Negro body and its only neck

would never be enough. Even the air

was frantic soldier, slapping blue aside

to spew its heat. He heard the bullets

as they wounded wood in search of pulse.

He smelled the stigma in the brick, the ruin

of every shelter they had built and blessed.

They built the blessed shelters and the banks

and busy offices, the barbershops,

the millinery with its smart chapeaux

and silken crowns for Sunday service, plus

the churches, where the congregations prayed

their shelters would be built and duly blessed,

the schools where children learned to write

their names, the shop where bolts of cloth

were cut for dresses, kitchens turned into

salons, that stink of flowery pomade

and burning hair. That place where music rose…

without a source or reason, mingling

with voices ’til the sky itself was song,

their tribulations waning with the dawn.

Their tribulations waned with every dawn

until the white man, so intent upon

his quaint possessions, rose to claim his dawn

again. He rose to claim his sky, his cloth

and nails, his wood, his bolts of silk, his shears

and pressing comb his many books and pens,

the market and its crooked stairs, he claimed

the women, then the men, and then the black

in all their mirrors, then their mirrors.

And Greenwood, glorified and built in search

of blessing, disappeared—gone was its whole

assembled soul, and all those loud black hands

were silenced, still. And were just hands again.

Were silenced, still. And were just hands again.

The men were silent, women still, amazed

and quieted beneath the dust from their

dismembered homes. Their shadowed skin

was still their own, just bulleted and brown,

no longer interesting, all that was left

was Negro, just the simple mud of it,

no lush brocade, chapeaux, or bank accounts,

no, just the haughty scraps of wreckage,

that slaver bobbing in the distance, perhaps

a snippet of a chain. There, someone’s hand.

A heart rifled to gone. Blood gumming up

the soles of one man ambling, weeping.

His only path had crumbled and collapsed.

White man keep beatin’ on that killin’ drum.

They just keep pounding on that killing drum.

Inside his cell, Dick Rowland wondered if

his skin against her skin, that second of

mistake, was all it took to end the world.

He heard the fading roar of colored men,

the horrifying sound of pleas with God

that ended in a panicked psalm. He heard

the frantic one-note squall of children, and

the women—Jesus, Jesus, Jesus. But…

he didn’t hear one white man’s voice, not one—

perhaps they’d died of too much carnage or

believed that they were God again. If so,

their craven clemency would save his life.

When you are born a question, you just know.

Whenever you are born a question, know

the answer’s bound to be some form of fire.

Oh, how those Negroes strode, in overflow,

entitled, voices tangling in a choir

that warbled privilege as if their days

were theirs. The storefronts wore their names

aloud. They ambled thru the twinkling maze

of Greenwood, assured and laying claim

to everything they set their eyes upon,

to all the shelters they had built and blessed

their tribulations waning with the dawn,

its silence, its still-rising. They found rest.

White folks kept beating on that killing drum,

too blind to know the hearts of those to come.