Three Poems

things to teach my son

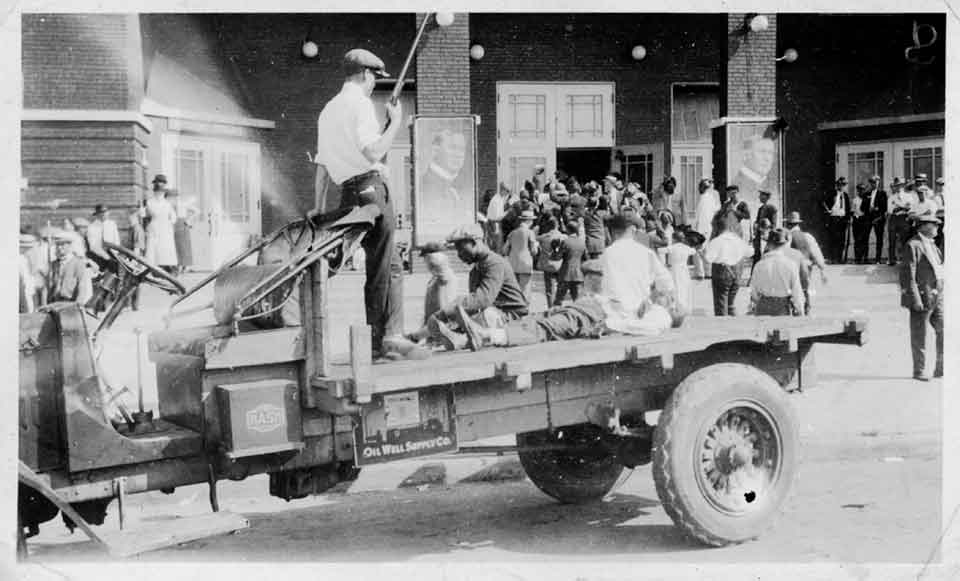

Tulsa, June 1, 1921

how to hold the line at first street. no escape

how to tramp backyard gardens

how to spot hiding places—attics, chicken coops,

long tablecloths

how to force-march men

how to command your peers

loot before you shoot

how a torch makes the cursive motion of a silent

e on every doorstep and window. no escape

loot before you flame

how to stand back from kerosene puddles like

piss after a romp, wide and wary of the fire

how to recruit the police

niggers who escape will bring reinforcements

from okmulgee

never let nobody see you flinch, son

how to hold your bile in front of the boys. no

escape

always grab something nice for your mom and

sister

how bullets can disguise themselves as rose, as

man, as sleep

shoot the dogs. take the horses

how to recruit the national guard

how to move a piano

how to find the good jewelry

how to include women—as drivers, browsers, to

hold the line at first street

how to use trucks, boxcars, boats, to make bodies disappear

the righteous rain of turpentine incendiaries, little

black birds dropping from the sky

how to recognize blackface and not shoot your

own

how to hide it if you do

how to make a rose bloom in the mind of a

nigger who shaped himself greek as a sigh

the magic of making a person a fiction

like israelites or the middle passage

how to turn a people into myth

Sarah Page,

Who schooled you in the Incendiary Arts?

Trained you to wield helplessness?

You, 17, full of hip-switch and giggle

adrenaline-high with the judgment

of a matchbook.

Who taught you

the Craft of Damsel? How to snatch breath

from the air?

He grabbed

your arm, not knowing it was made of fire

and fuel. It’s since been a century fraught

with reverbed 911 screams.

Cities still burn.

Your comfort still kills.

Dear Neighbor,

Mysteriously, unsigned warnings began to appear on the doors of homes and in an Okmulgee, Oklahoma . . . newspaper. These warnings prophetically announced the dire consequences that would befall African Americans who remained in Oklahoma after June 1, 1921.

I’m pinning this to your door because I know

these words will be lost to history.

Let me confess. You take money from my

community. You take our jobs.

My little girl grows too much for shoes. My boy

looks like your pickaninny should.

He asked for your boy’s hand-me-downs. You

undermine everything I teach them

about the White Race. They get nigger diseases

like scabies and I don’t know why.

My wife compares me to you. My mother does,

too. In you, I see my failures

and I hate us for it. The big boys downtown see it,

too. They can smell it on me.

Despite this, I still own you. The sun goes down

on Greenwood June 1st.

Author’s note: The epigraph to the poem “Dear Neighbor” comes from Hannibal B. Johnson’s 1998 book, Black Wall Street.