I Dream of Greenwood: The Nightmare and the Dream

I slept with a pink seashell nightlight until I was sixteen years old. I was afraid of the dark.

I still am. Most nights, I covered my head with the sheets, peering out only occasionally to see the shadows dancing on my wall. In the morning, my little body was drenched in sweat and stripped down to my panties. My mother always asked what happened to my pajamas in the middle of the night. When I wasn’t curled up in a ball under a pile of covers, I was brazenly sleepwalking throughout the house, unaware of what goes bump in the night. One night, I unlocked the front door to my house, walked outside, and stood on the front lawn in my Disney princess nightgown. I woke up outside, walked back into the house, down the long corridor, and crawled back into the safety of my bed.

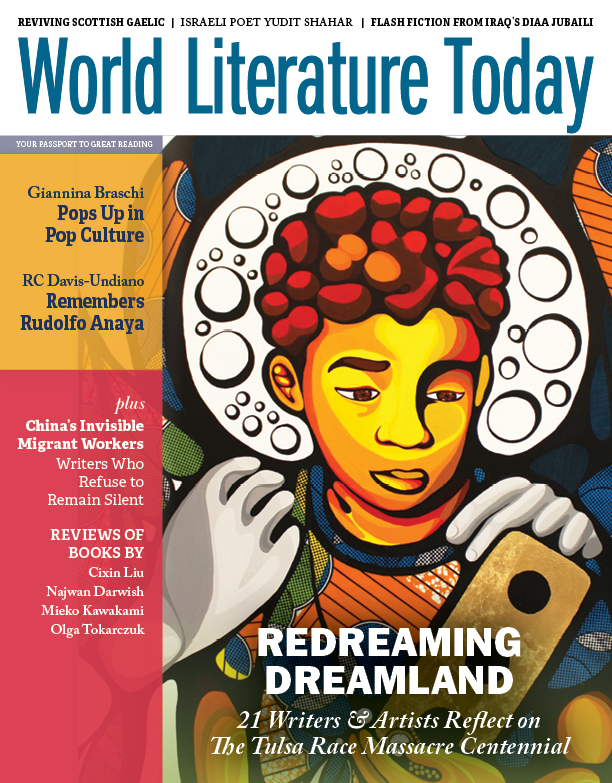

When World Literature Today and OU School of Dance faculty Leslie Kraus asked me to create a piece for the Tulsa Race Massacre Centennial, I initially didn’t want to take it on. This kind of work required a lot of care, and frankly, as a transplant to Oklahoma, I wasn’t sure if I should be the one telling this story. I wasn’t sure I wanted to perform Black trauma within the walls of a predominantly white institution. I asked for some time to think about it, and then the pandemic happened, and life became about staying safe and focusing on the day-to-day. The pandemic worsened with no end in sight; protesters worldwide filled the streets, asking for justice for George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, and countless others.

I began the dance research process in the summer of 2020 without providing a clear “yes.” I spent mornings in my garden thumbing through Riot on Greenwood: The Total Destruction of Black Wall Street, compiled by Tulsa activist/educator Eddie Fay Gates. In 1998 Ms. Gates became chair of the Survivors Committee of the 1921 Tulsa Race Riot Commission. She interviewed more than two hundred survivors and three hundred descendants, documenting the narrative experiences Tulsans connected to the massacre in hopes of unearthing a painful history and seeking reparations for the families seventy-five years later.

Every time I opened the book, I landed on the story of Jimmy Lilly Franklin, who was six years old at the time of the riot.

“At night, I dreaded going to bed. I was desperately afraid to go to sleep because of the fears I harbored about the sinister, menacing, hooded invaders who looted our home of prized possessions and then, with lighted torches, set fire to our homes. The acrid smell of smoke constantly burned in my nostrils as I twisted, turned, talked, and cried aloud while I slept so restlessly and dreamed, ” Jimmie recounted.

After reading Jimmie’s story, I read several others and noticed a common thread of nightmares and lasting fear following the massacre. What happens to a young body, to a youthful spirit when confronted with that level of unexplainable trauma?

What happens to a young body, to a youthful spirit when confronted with that level of unexplainable trauma?

What happens when you are a child and the monsters you fear at night are not imaginary but flesh just like you? What happens when they live in your city?

I didn’t know about the Tulsa Race Massacre until I was in my mid-twenties, and even then, much of the discussion centered around the destruction of Black Wall Street. This glittering gem of Black determination and self-sufficiency became myth-like in my artistic and progressive circles. Except it wasn’t a myth. It was real. The place was real, and the people were real.

Creating work about the Greenwood neighborhood, we chose to see through the eyes of the children, who described the Kimball pianos in their homes, their neighbors to the left and the right of them, and the pride they took in Detroit Avenue, where the Black doctors and lawyers lived. The same children who played hand games and hopscotch on the sidewalk lost their innocence when their town burned to the ground.

J’aime Griffith (my artistic collaborator for this work and OU School of Dance Grad Student) and I gravitated to the words of Dr. Olivia Hooker, a survivor featured in Gates’s book and a video interview shared with me by Mechelle Brown from the Greenwood Cultural Center. In the interview, she describes hearing what sounded like hail on her house’s windowpane on Independence Street. Her mother brought her to the window and had her peer through the blinds. “That’s a machine gun out there; see the American Flag on it; that’s your country shooting at you,” said her mother. Dr. Hooker was six years old at the time of the massacre.

The city of Tulsa and the police department provided weapons, deputizing the angry white mobs, who stormed through the Greenwood District, shooting up homes, businesses and dropping bombs on what they referred to as “Little Africa.”

I think of young Black kids today learning about the police shooting of a young Black woman, Breonna Taylor, while she was asleep in her bed. When what you fear is tangible and possible, it changes the psyche.

When what you fear is tangible and possible, it changes the psyche.

When I was thirteen years old, I came home from school and found my parents huddled around the television debating what would happen with the Abner Louima case. Louima, a Haitian immigrant who was wrongfully arrested outside of the Rendez-Vous nightclub on Flatbush Avenue, was then taken to the infamous 70th precinct jail, where he was brutalized and sexually assaulted by multiple police officers. My parents struggled to explain the details of the violence and forced sodomy, but they had no choice; the news replayed the image of Louima cuffed to a hospital bed, his face swollen and battered over and over again. I can still close my eyes and see his face. I remember feeling angry and embarrassed; my body fluctuated from flushed to chilled. Our Haitian community in the burbs mobilized and headed to Brooklyn, marching with Al Sharpton, carrying signs, and chanting “Justice for Abner Louima.” Thousands of people marched on Flatbush Avenue to the steps of the precinct, some brandishing a toilet plunger, the purported weapon used against Louima.

Two years later, the streets were flooded again with protests after an unarmed twenty-three-year-old Guinean immigrant, Amadou Diallo, was fatally shot forty-one times by NYPD in the Bronx.

It was then that I began to see that Black people couldn’t expect to be protected in the same way as white people in America. We were living in a different version of this country compared to my white friends and their families.

Before the Diallo and Louima cases, the horrors of racism felt cinematic and far away.

At the age of thirteen, I had never heard of Emmet Till, and the details of the battery of Rodney King were fuzzy. I felt safe in my suburban hometown of Spring Valley, surrounded by other Black and Brown immigrants and the white families who either chose to stay in the neighborhood or hadn’t found a reason to leave quite yet.

In hindsight, I don’t know if it was safe. I am sure my parents shielded me from what they could when they could.

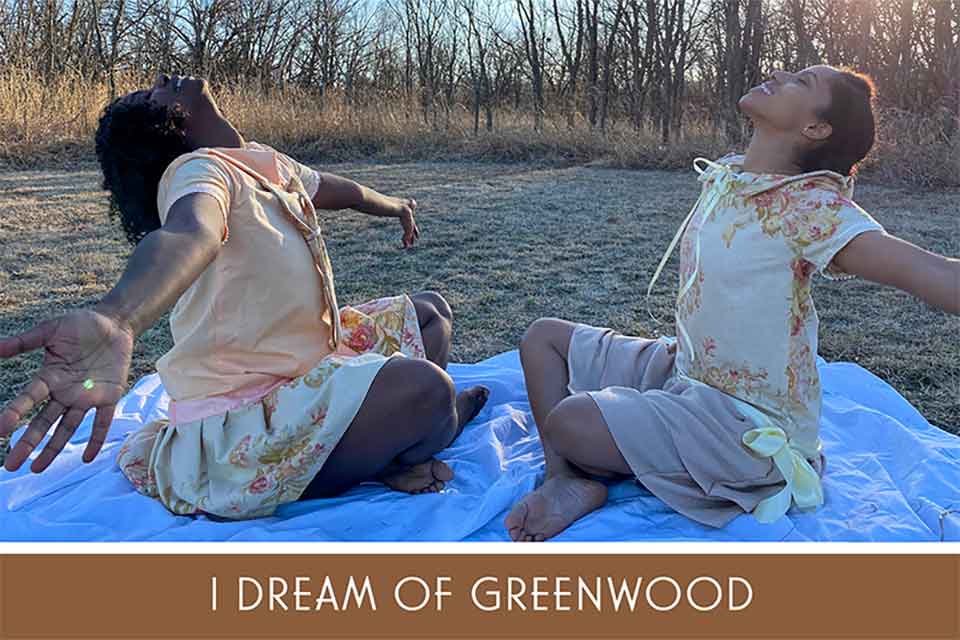

I recognized something in the stories of the massacre survivors that made me remember our human experience is universal, even if our circumstances are not the same. I remember what it’s like to play hopscotch on the sidewalk, hand games with my friends, and I remember what it’s like to feel jolted out of a sense of security. For this reason, our dance, I Dream of Greenwood, holds space for both the nightmare and the dream.

I want to take the space here to thank the survivors and their families for sharing their stories with Ms. Gates. Thank you to Mildred Mitchell Christopher, age seven; Jimmy Lilly Franklin, age six; Ernestine Gibbs age nineteen; Olivia J. Hooker, age six; Vera Ingram, age twelve; Eldoris Mae Ector McCondichie, age ten; and Dorothy Wilson Strickland, age nine at the time of the massacre.

University of Oklahoma