The Amphitheater

for Juan José Hurtado, in memoriam

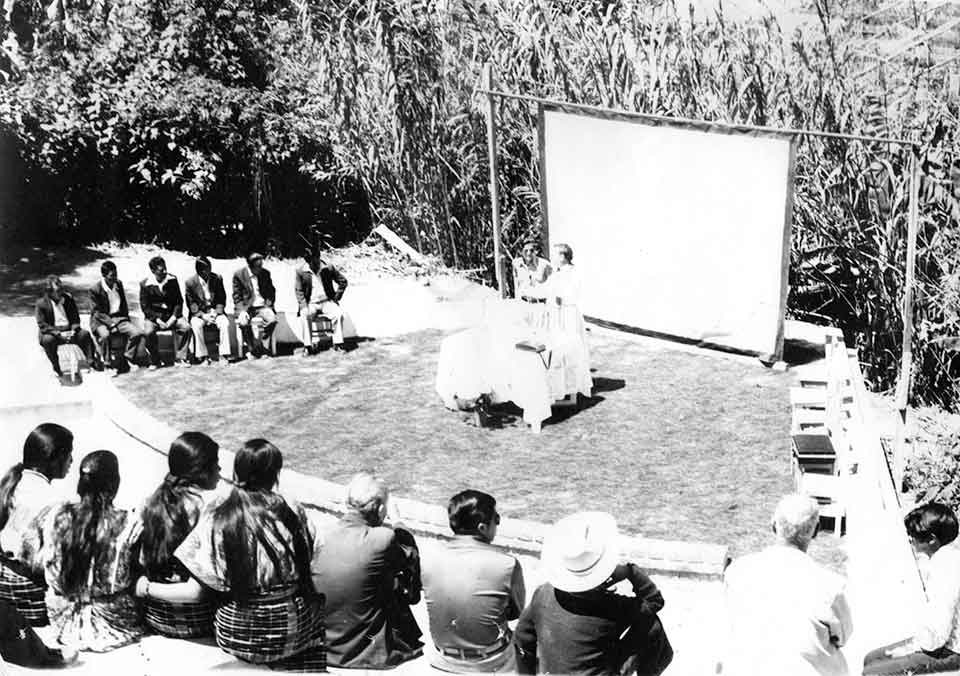

For the narrator of the following crónica, 16mm films made by Kaqchikel villagers, flying ants, and dragonflies all flicker in the historical shadows of a ruined amphitheater that, in the Guatemala of the 1970s, “ceased to exist.”

He handed me a torch of burning ocote. Hold it up like this, he said, showing me how with his own. Then I received from him an ancient clay tinaja. I liked the feel of the cold damp earth in my hand, as if I were holding a piece of the past, of a time more diaphanous and primitive and painted in shades of ochre. Let’s see if we get lucky and one of them falls, he said. We began to walk slowly through the now empty and dark streets of San Juan Sacatepéquez.

I thought I felt a soft drizzle on my face. Although it could have also been nothing more than the evening mist. Or my nerves. We passed the vacant lot where I had left my car. We passed some market stalls around the central plaza, already closed and covered with black and blue plastic tarps. We passed a cantina that was probably a brothel. We passed a bundle of green bananas lying in the middle of the street. We passed a row of crumbling houses, and I remembered the earthquake of 1976. We passed a small bridge that crossed a black and rancid creek. We passed by a large piece of land full of apple trees and something that in the night looked to me like a grandstand descending to a small stage. Like an amphitheater in ruins—like the bleachers of an amphitheater in ruins. I asked Ramón what it was, and he stopped and told me it had been a movie theater. But years ago, he said. When I was young.

He placed his clay tinaja on the ground, pressed between his black rubber boots. He took a cigarette out of the pack of menthol Rubios and lit it with the fire of his torch. I accepted one. I also lit it with the fire of my torch. I felt prehistoric.

As a young man he had seen there movies of Cantinflas and of Pedro Infante and some cowboy movies.

Ramón told me that, in the seventies, some doctors from the city came to the village on weekends and showed there, pointing to the small amphitheater with his cigarette, all kinds of movies. He told me that the doctors had built it themselves, among the apple trees. He told me that as a young man he had seen there movies of Cantinflas and of Pedro Infante and some cowboy movies. He told me that the doctors also showed short films, in Kaqchikel, made by the villagers themselves. He told me that the doctors had a small sixteen-millimeter camera, and they would give it to the local people and teach them how to use it and ask them to make very short films in Kaqchikel about nature, about basic health, about life in the village. He told me that the doctors would then show those short films in the middle of the Cantinflas and Pedro Infante and cowboy movies.

I looked down at the amphitheater among the apple trees (I smelled or thought I smelled the apple trees in the night). I noticed that the bleachers were overgrown, abandoned, useless, and I suddenly imagined all the indigenous people of San Juan Sacatepéquez sitting there as they watched the short, blurry, sixteen-millimeter films in Kaqchikel, made by themselves. I asked Ramón what had happened to the movie theater. Oh, he said, it ceased to exist. And his voice hurried to hide in the night.

But it wasn’t difficult for me to guess the rest of the story, to guess why something like that could not exist (to use his word) in the Guatemala of the seventies. I asked Ramón what the short films had been like, if he remembered any of them. But he just threw away his cigarette, crushed it into the ground with his black rubber boot, and kept walking.

Soon, almost without realizing it, we had left the outskirts of the village. We kept moving forward and reached a trail and began to walk among old oak trees, up the mountain. The ground was muddy and slippery. I looked back fleetingly. The entire village had disappeared.

In front of me, while hacking away some loose branches from the trail with his machete, Ramón was telling me about the origin of the village’s name. San Juan, he said, is for John the Baptist, the patron saint of the municipality. Sacatepéquez, he said, is actually two words in Kaqchikel. Sacat, which means grass. And tepec, which means hill. I asked him about the origin and meaning of his own name. Ramón López Chumil, he announced softly but not without pride. Ramón López is for my father Ramón López, and my grandfather Ramón López, and my great-grandfather Ramón López. Chumil, he said, is my mother’s last name. It means star, in Kaqchikel.

After a while we stopped to rest, and I asked Ramón in a whisper (as if my voice might scare them away) if he had seen any already. Not one, he said. They haven’t come out. Not as many come out as before, he said, and spat a long slimy drool to the ground.

He was silent for a moment, panting lightly, as he tucked the hem of his pants into the big black rubber boots.

The zompopos de mayo would fall from the sky, he said with the momentousness of a preacher.

Before, when I was a boy, he said, as soon as the first rains came in May, we would go up the mountain with my father and catch zompopos de mayo. They would fall from the sky, he said with the momentousness of a preacher. Imagine that. They would just fall from the sky and fly toward the flames of the ocote, and with my father we would pick them up from the ground and put them in our tinajas. There wasn’t enough room for so many in our tinajas. Then we would return to the house and my mother would throw them all into a basin full of water, to wash them before removing their wings and legs and heads, since one only eats the small round body of a zompopo. She would then put the round bodies on the comal and toast them with a pinch of salt. I thought I saw Ramón smile in the amber light. Very tasty, he said. Only for special occasions.

We continued through the forest in silence, me slipping a little in the mud with each step, waiting for the zompopos to fall from the sky and fly into the flames of my torch. I wanted to see them, to catch them, to savor for the first time that tasty and salty and crunchy snack reserved only for special occasions.

We reached the top of the mountain. Ramon, crouching, his gaze sleepy or resigned, was silent. I thought about telling him not to worry, that I understood that the sky had already been emptied of zompopos (I would have to wait a few years before finally tasting one, on a not very special occasion, inside a nameless dining room on the shore of Lake Amatitlán). But I just asked him for another cigarette. And we both waited hopelessly as we smoked in the minty muffle of the night, our torches by now barely lit, our ancient clay tinajas almost forgotten on the ground.

There was a short film about a vaccine, Ramón suddenly said in the half light. Among the films the villagers made, he added, for the doctors from the city. Although he was still crouching in front of me, I could barely see him in the moonless night. Chikop, it said on the screen at the beginning of that short film, said Ramon’s voice in the darkness. Chikop, I repeated. It means little animal, in Kaqchikel, he said. First, he went on, there appeared on the screen a boy from the village, his face all painted with red dots. Then a healthy boy appeared next to him, but after a while that boy’s face was also covered with red dots. Child after child appeared on the screen, and each one’s face would suddenly be full of red dots. Chikop, said the voice in Kaqchikel. Not God, said the voice in Kaqchikel. Then a syringe appeared on the screen, and the voice in Kaqchikel said that the red dots could be removed with a vaccine. That it was free, said the voice in Kaqchikel, that one could come there on weekends to get the vaccine from the doctors from the city. Then all the children would be on the screen together, playing happily, their faces clean. And the film ended.

There was a short film about the cat technique, Ramón said. That’s what the doctors from the city called it, the cat technique. I again felt a gentle drizzle on my face. The only light came from the glow of the embers of our ocotes. On the screen there was a man walking through the forest, said Ramón’s voice in the night. The man then pulled down his pants and squatted right there in the forest and relieved himself next to a nearby bush. Then the man’s fingers appeared on the screen throwing dirt on his droppings, covering them with dirt using his fingers. Ramón made a brief pause, necessary to smoke or maybe to overcome his modesty. And a voice in Kaqchikel said that one had to do as a cat does.

There was a film of a dragonfly, Ramón said in the night. B’atz’ibal, said a voice on the screen. It means devil’s needle, in Kaqchikel, he said. The dragonfly on the screen was crashing against the glass of a window. Over and over and over. The dragonfly wanted to go out, but the window was closed. A voice in Kaqchikel said that the nature of a dragonfly is to fly back to the banks of the river.

There was a film of the villagers’ feet, Ramón said. The villagers were all lined up. They were waiting for something. But on the screen were only their bare feet. The film on the screen moved forward in the line, but one only saw the bare feet of the villagers. Nothing else. Just bare feet. Bare feet of men. Bare feet of women. Bare feet of children. Bare feet of old people. Many bare feet. All in a line, as if hoping to move forward toward something. But the only thing that moved forward was the film. The bare feet of the villagers never moved forward. K’o ak’wala’ taq winäq choj chik nimoymot yetzu’un, said the voice in Kaqchikel. There are people who are still young and no longer see well.

The only thing that moved forward was the film. The bare feet of the villagers never moved forward.

There was a short film about a half-naked woman, Ramón said. I could now barely make out his faint silhouette crouching and small in the night, but I was sure he had said it to me with the mischievousness of that child sitting in the amphitheater among the apple trees, back in the seventies. I heard him exhale a puff of smoke. First a cow appeared, Ramón said, and a voice in Kaqchikel said that the mother cow’s milk was for the calf. Then a goat appeared, and a voice in Kaqchikel said that the mother goat’s milk was for the kid. Then a dog appeared, and a voice in Kaqchikel said that the mother dog’s milk was for the puppy. Then a woman from the village appeared, he said, and she pulled out one of her big brown breasts, and a voice in Kaqchikel said that the mother’s milk was for the baby. Ramón laughed softly, as if with shyness, or as if with cunning, or as if with the serenity of his years. In the night, somewhere near us, a frog chirped.

Editorial note: “Highland Maya civilians [in Guatemala] were the victims of a thirty-six-year civil war in which 900,000 of them were displaced from their lands, many of them becoming refugees in Mexico, Belize, and the United States, and another 166,000 were killed or ‘disappeared.’ By the time a cease-fire was declared in 1996, the Maya constituted 83 percent of the war dead. A United Nations study stated that Guatemala’s war policies had been tantamount to Maya genocide.”—Lynn V. Foster, Handbook to Life in the Ancient Maya World (2002)