Wandering Houses

When a landscape is in motion, people and buildings are compelled to follow. This is a basic rule when living with the North Sea. But Børglum Abbey and its willingness to move is a different story altogether, and that was why Dorthe Nors sought it out.

It takes a certain build to stay standing on this line. You’ve got to bend, walk sideways. The old houses have buckled at the knees, but still hold firm. They’re digging in to shelter behind the dunes. They shiver on windswept plains behind gust-warped trees. They have hipped roofs and little windows. Everything is about making themselves small, against the pressure of the wind. It produces beautiful houses in concord with the surroundings and themselves. Despite these precautions, many buildings have ended up being blown away, swept over with sand, or taken by the sea.

The people who developed the historical building practices along this line knew they weren’t living on a western coast. They were living on an eastern one: the eastern coast of the North Sea. If you think of the sea as a delineated geographic shape, then from above the North Sea looks a bit like France. It tapers toward the English Channel; it presses up against Scotland, runs around Norway where the country is heaviest, and down along this eastern coast. The North Sea is a nation without a capital, but with its own powerful identity. At the transition between sea and earth, its vast energy has nowhere to go and surges deep into the land. A piece of the slopes, the dunes, dashes into the sea. Then the fjords break through, then the sea builds tongues, and by the time winter is over the dust-green dunes are as white as Alpine peaks with sand. Sandknog, my grandmother called the phenomenon. Sand drifts. She grew up in the early 1900s in the inland dunes of West Jutland, where the wind sweeps in almost every day. It paints the land with sand and salt. Sand drifts could eat a farm, a church, a small community. It insists that accommodations be made, and there are fierce forces at play. Eager for a closer look, I drove north toward Vendsyssel. I wanted to visit Børglum Abbey and the scenery around it.

The North Sea is a nation without a capital, but with its own powerful identity.

It was late June, and the abbey perched on a crest was a safe distance inland. It was the dead calm of summer, and I walked up to the old mill on Miller’s Hill to view the landscape and the abbey from a distance. As I stood there, I could—with a little wishful thinking—sense the place where a tiny church had once existed to the north. It had been pulled down before the sea could take it. Now only the bones of the dead occasionally come rattling down the ice-age slope.

I once bumped into a pale tourist by the sea where I live. She was holding a jawbone in her hand.

“What do you do with this sort of thing?” she asked, holding out the jaw to me. I’d been living by the sea four months. The locals thought of me as a stranger. Strangers thought of me as a local.

I told the tourist that she should call the police. You can’t go round picking up body parts without reporting it to someone.

“But is it a dead fisherman?” asked the tourist, and I said it could also be a sailor from the Battle of Jutland, which had claimed well over eight thousand lives.

“And they don’t all stay out there, of course,” I added. “But it could also be from a dead man’s mountain.” The tourist was holding the jaw with two fingers. “I mean, from a mass grave of people who drowned.”

“There are mass graves here?” asked the tourist.

“There are mass graves up and down the whole coast,” I said, “and the sea eats away at them.”

At that, the tourist handed me the jaw, as though it was my responsibility.

“Call the police,” I said and handed it right back.

From the site up north where the Mårup church had stood for centuries, and where now only half the churchyard remains, the dead also sift down into the sea at regular intervals and frighten tourists. Sometimes remnants of bone are left devoutly placed on top of the gravestones. Some considerate person disposing of the evidence. You can end up with too many calls to the police when a churchyard is drifting into the sea.

Speaking of the dead, to the north-west I could also spy the colossal dune of Rubjerg Knude. Now that’s a sand drift. It has claimed the lives of more than one structure. Not so very long ago the lighthouse that sat atop it was put on roller-skates and transported ninety yards further inland. Yes, they put a lighthouse on wheels and moved it, because it was about to drop into the sea. It looks so lonely in its desert, the lighthouse. The sand beneath it has long since eaten up the keeper’s cabin, and in ten years, twenty years, who knows, the tower will have to be moved again. It will be impossible to save in the long run, that’s just the reality of it; and further south toward Løkken, the remains of summer cabins devoured by the sea poke out of the clay slopes. Septic tanks, drainage pipes, woodsheds—all are wandering down to the sea, accompanied by the Regelbau bunkers. The latter can be found all over the coast, beaten and battered before finally being swallowed by the breakers. The sea picks the meat off them, storm by storm. And there they stay, marked by big Xs so that swimmers don’t end up impaled on their rusty skeletons. Once upon a time, they were built to defend a “Thousand-Year Reich.” The Thousand-Year Reich was afraid its enemies, the Allies, might see the coast for what it was: an eastern shore. As such, it was here that the invasion might take place. Assuming it survived the sandbars. And so the Thousand-Year Reich built a fortress out of concrete. Then it lost on every other front, and the sea has been playing dice with the megalomaniacal fragments ever since. Before it swallows them. One by one.

The sea picks the meat off them, storm by storm.

When a landscape is in motion, people and buildings are compelled to follow. This is a basic rule when living with the North Sea. But Børglum Abbey and its willingness to move is a different story altogether, and that was why I sought it out. It sits on a hill by an ancient crossroads, looming unbudgeably above western Vendsyssel. An old center of power on a fertile settlement. There was a royal estate on Børglum Hill in Viking times, but in the eleventh century the Danes became Christian and the site became a bishop’s seat. It was home to the Catholic Premonstratensians and later established as the order’s motherhouse in the north. As a place name, Børglum first appears around 1100 as Buhrlanis. The name is made up of two Old Danish words: burgh and lan. Burgh means either borg (castle) or bakke (hill), while lan is the same as the English “lane.” Børglum, then—a royal estate, an abbey, and now a country house—has been known since time immemorial as “the castle by the road,” or something along those lines. The crossroads is still there. The abbey stands where it has stood for a thousand years. No hurricane can topple it and the sea can’t reach it. It has risen above earthly circumstance and will not disappear. Except that, sometimes, it does.

My friend, the author Knud Sørensen, was born in 1928 and has written about Børglum Abbey’s peculiar restlessness. Once, in the early 1960s, he and his wife Anne Marie drove down to see the abbey on a clear, moonlit night. They were driving an old Citroën with the children on the back seat, and when they arrived, they couldn’t find the abbey. They had to drive around searching for it. Knud is a Vendsyssel man by birth. He’s been looking at Børglum Abbey since he first opened his eyes. His wife, too. They parked the car exactly where they always parked it, and they looked at the place where the abbey was supposed to be. Right there. But, as Knud writes in his memoirs, it wasn’t right there:

We got to the top and we stopped, and we looked around us. Only then did it really dawn on us that we couldn’t see a thing. That is, we could see plenty of things—we could see far across the landscape, and we’d seen the lighthouse at Rubjerg Knude in the north-west as we drove up the hill—not just flashes, but definitely the white tower as well, we recalled. And from this vantage point we could make out what had to be the sea, and we could see for miles over the countryside beneath the bright sky. But we couldn’t see Børglum Abbey. Børglum Abbey wasn’t there.

I’ve always found it astonishing that a person so pragmatic, so down-to-earth and fundamentally scientific as Knud, could have had a paranormal experience. It also astonishes Knud. Why him, of all people, a man who does not believe in magic realism, who prefers new simplicity? Knud isn’t just a poet; he’s also a trained surveyor. But perhaps it is surveyors that Børglum Abbey is eluding, refusing to submit to that sort of profane tomfoolery. The abbey belongs to eternity. “Measure this, Knud Sørensen,” the abbey thinks, climbing into it for a brief moment: eternity.

But Knud is connected to this landscape, and he knows that identity must be formed in the schism. You carry the place you come from inside you, but you can never go back to it. It’s a riddle, but such is life, and Knud set out for Copenhagen as a young man. While studying at the Agricultural Institute, he wrote poems about Vendsyssel in secret. He wrote poems about Børglum Abbey on its hill and Vrejlev Priory a little further inland. He longed to go home to the countryside, the way you might long to see an old member of the family. The landscape made him a poet. Pragmatism made him a surveyor. Clearly, on that moonlit autumn night, Børglum Abbey was willing to move for both.

The abbey excelled at sober-mindedness, I thought, and its asceticism drew no colour from the worldly extravagance around it.

As I stood there in the summer’s light, the white walls of the abbey were trembling. Flowers trickled up everywhere, but the abbey felt strict and unmoved. It excelled at sober-mindedness, I thought, and its asceticism drew no colour from the worldly extravagance around it. Crossing toward the place where Knud’s Citroën had sat idling in the early 1960s, I bought a ticket from a friendly man at the museum shop. I asked him what route I should take around the abbey. He said that if I wanted to learn a bit about the place, there would be plenty to read as I was walking around. I asked where I should go first if I wanted to get the maximum impact quickly.

“The abbey church,” he said.

“Is it open?”

“They can hardly shut it,” he said, and I walked straight over to examine the openness of the church.

I stood quietly inside for ages. I tried to find suitable adjectives, but kept being drawn back to eerie. Was it that the church felt chronically cold, despite the sun in the courtyard outside? Was it the floor’s corpse-storing unevenness? The black-painted choir? The heavy velvet curtains flanking the altar? The thought of bishops pushing their baroque bellies through the velvet to make their theatrical entrances? Yes, that’s what it was, and it was the cold, and the sepulchre, and it was Christ on the cross with his crazed face, and the armless statue of the Virgin Mary with the Infant Jesus in her lap, his head knocked clean off. More than anything else it was the baptismal chapel: a door, a square room and a font in the middle, crowded round by countless small, malignant-faced boys. Putti, I assumed.

It was as if time did not obey the laws that existed in the courtyard, where visitors sauntered around in sandals to the happy din of the swallows that had just arrived. Yes, it was as though there was slushy snow inside the church. Like it was a winter’s day I was visiting, in an age beyond my own, and that only once outside in the courtyard could I pick up my relatively chronological wanderings through life.

Knud is a good friend. I believe him. He doesn’t lie, and as I strolled through the landscape amid the chalk-white manifestation of the abbey, I saw it in my mind’s eye on a day a few centuries ago. One moment I sensed its age, the next its potent presence. The abbey insisted upon itself so vehemently that it was disconcerting. It played all sorts of psychological instruments to get your attention, and if I’d had Børglum Abbey next to me at dinner I’d have spent most of the time hiding in the loo. In the mild summer weather, I decided to drift toward the café. There I could get some distance from the atmosphere of the abbey, and I was hungry and thirsty for coffee. I noticed a salmon dish called “Mrs Rottbøll” on the menu, named after Børglum’s current owners. They also had “Stygge Krumpen” on the menu: three types of cheese, one of them apparently so wicked it could make you cry. Which is fitting, because there was nothing tender-hearted about the last Catholic bishop at Børglum. In fact, Stygge Krumpen had been so vile that people said it was his fault the abbey occasionally vanished into thin air. I heard that from Knud. He got a letter from someone who told him. Stygge Krumpen had been so loathsome when he stalked the halls of the abbey that after he died he burned in hell. As extra punishment, he and his entire abbey were hoisted into the air every now and then for a whizz around the sky. Just so he could see what he was missing. During these heavenly excursions, the abbey was invisible from the ground and it was at one such moment that Knud had visited. Everything had been as clear as an etching in the moonlight—but not Børglum Abbey.

I ate a Mrs Rottbøll for lunch. Precious few people will name a bad dish after themselves. Afterwards, I took a comfortable walk around the abbey, through the herb garden and across the courtyard, avoiding the sucking door of the church. Everything was still. I sat down under a big, old oak in a little garden east of the stable block. The tree was stout and inflexible, its branches groping wildly toward the sky. A large privet hawk-moth sat on the trunk, resting during the day. At night it would go fluttering up between the branches.

Time and again, I’ve questioned Knud about what he thinks happened to the abbey that night with the Citroën. He replies each time that he doesn’t know. I’ve asked him if it might be because places can become so old and full of stories that eventually they start sifting through their memories? That maybe, that moonlit night, Knud and his wife were accidentally caught up in Børglum Abbey’s memory of itself when it was still a royal estate? Knud replies he doesn’t know. I’ve asked him if we might be dealing with some sort of time warp? Knud replies that others have suggested that theory to him, but that he doesn’t know. I’ve asked:

“Do you reckon it’s a parallel universe?”

“Could the disappearance be a manifestation of the all-time phenomenon?”

“A magnetic field, a type of cosmic elevator?”

“I don’t know, but it sounds brilliant,” is Knud’s reply.

To cut a long story short, he doesn’t know, and it makes no difference to him. He thinks it works as a story in and of itself. Stories, especially the good ones, are real, and he believes in those. I do too, just as I believe Knud. But I’m not a surveyor. I prefer to take a rather more abstract view of the flowing and cosmic aspects of everything, I thought, and as I sat under the tree I stuck my hand in my pocket. Inside was a lump of amber I’d found by the sea on the way up. I like to put them in my mouth and walk around for a while, holding them there. They feel so warm against the tongue. But the one in my pocket was too big to wander round with it in my jaw. It was milky, round and a little like a child’s fist. I looked from the lump to the limed walls of the abbey. They flickered, alive. Nature has all the time in the world, I thought—just look at the amber. It evinces no particular regard for civilization—just look at the septic tanks, the lighthouse. Civilization is a snapshot. Forces such as the sea’s, the wind’s, the rain’s, the ungraspability of the universe, to say nothing of the Earth’s glowing core, compared to your reality, strung frail and taut between birth and death? Your concepts of space? The universe would laugh if it knew that you existed and could hear your little joke.

The universe would laugh if it knew that you existed and could hear your little joke.

I spent a summer living with an American and his fiancée. It was on the eastern shore of Ringkøbing Fjord on the central coast. The fiancée was a childhood friend of mine, and we took several long walks in the evening. We sat at the end of a jetty and gazed across the fjord toward Holmsland Dune, where Lyngvig Lighthouse flashed. I often sat there alone, too, staring at the lighthouse while I thought about where to go. I’d come from New York that summer, and I was moving to Copenhagen in the autumn, but more than that. Where did I come from, and where was I going? I didn’t know.

The American told me one night that he often got lost on an ancient heath on the eastern side of the fjord. The landscape shifted beneath him when he walked there. “Pure and simple,” he said in English. I suggested it was his sense of direction letting him down. He took the insult in his stride. In America there were landscapes so vast that you knew nature had a consciousness all its own. Its sense of time, space, direction were unmoored from our small conceptual world. The locals knew that. They didn’t sit on jetties, staring at lighthouses while waiting to move somewhere else. They accepted that it was the lighthouse that could move; or, more precisely, the sandbar beneath it, and that it was merely a question of moving with it. Of being on good terms with the forces of the universe. Having faith that one day you would reach some other place—or home.

The American’s story made a kind of sense, I thought. I suggested it to Knud when I questioned him about the vanishing of Børglum Abbey, and he said,

“Brilliant. But I don’t know.”

It’s a humbling position to be in, I thought, leaning up against an oak tree with the milky amber in my hand: not knowing, not believing oneself big enough to lay bare the riddles of existence. Stick to measuring the landscape as the landscape lies. Don’t dream of other dimensions, simply be grateful for the dimension you’ve been dealt. Maybe it’s the Vendsysseler in Knud, I thought, and tilted back my head. I eyed the crooked branches of the oak. How big had it been, I wondered, when Knud was a little boy? Probably more or less a tree already, I guessed. Maybe Knud had passed it as a child or a young man. He could have sat leaning against it, as I did now. He could have looked at the abbey, there as it has always been there. Throughout the lives of his ancestors, of his parents, and his life. As a husband, father, and surveyor, he returned one night to find the point of his departure. “This is where I came from.” And it was gone. One cloudless night he got out of his car and went to meet it. The landscape seemed unreal to him. The colors disappeared, the contrasts grew starker, and Børglum Abbey wasn’t there.

Could he see the big oak tree, outlined in the moonlit night?

Or had that vanished too? Still unsprouted, or long since felled?

I looked at the big hawk-moth. Its feelers were like white antlers against the dark bark. Its head was as soft as a cat’s. It had been a caterpillar once. Then it transformed, and as I sat there watching the summer tremble, winter cocooned inside it, I knew only one thing: every so often, Børglum Abbey disappears. And someday, when I drive up to see Knud, he’ll be gone as well. Yes, someday Knud will vanish, and no one will know where.

Translation from the Danish

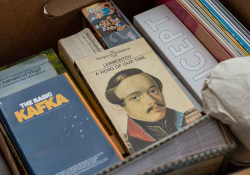

Editorial note: “Wandering Houses” is from Dorthe Nors’s collection A Line in the World: A Year on the North Sea Coast, translated by Caroline Waight and forthcoming from Graywolf Press in November 2022.