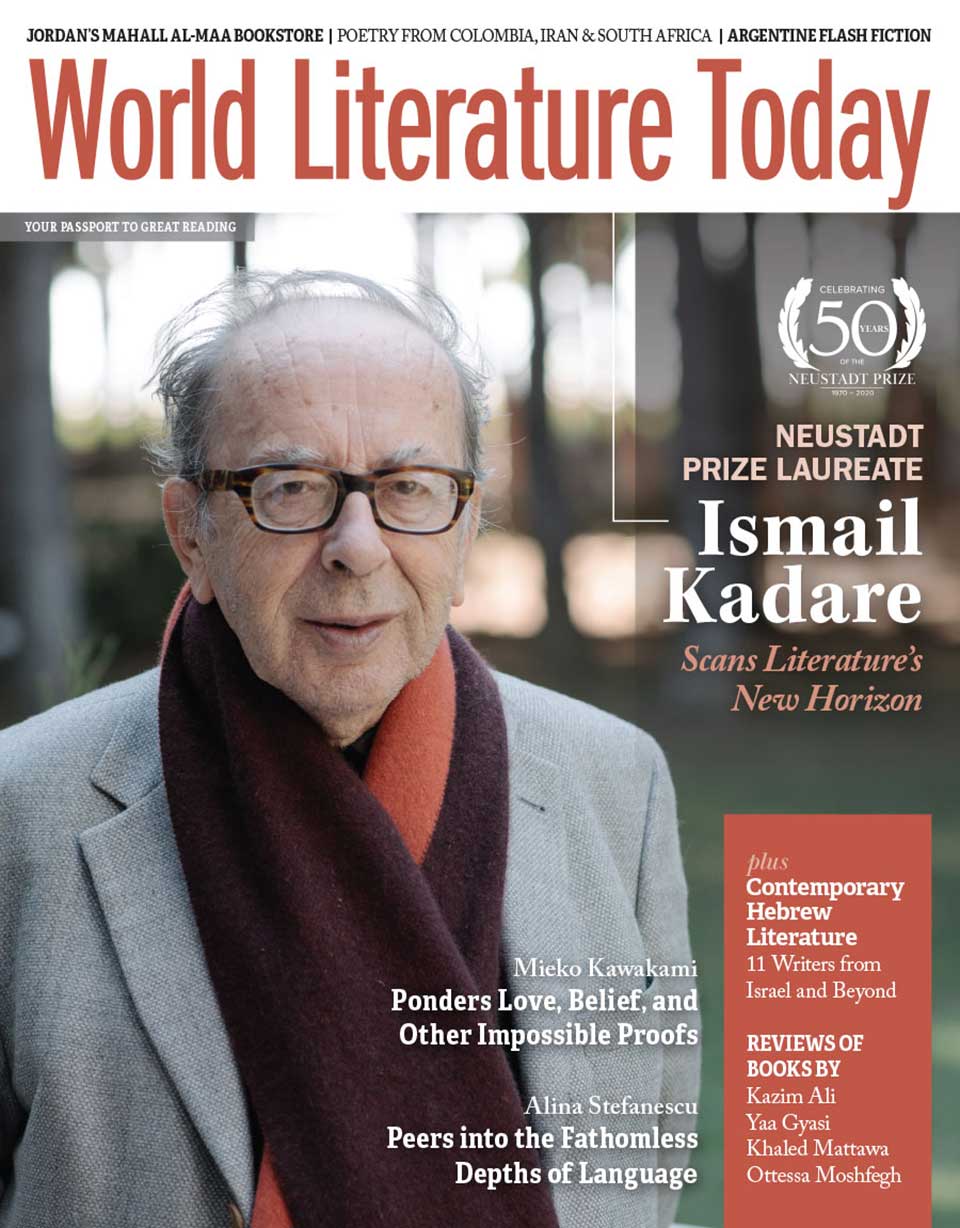

Ismail Kadare and the Worldliness of Albanian Literature

Neustadt Prize winner Ismail Kadare transports a reader to the Albania of her grandparents’ generation with his fiction, which speaks to timeless global themes alongside its more localized exploration of the Balkan peninsula.

So much of Ismail Kadare’s art is inherently Albanian. From the language that emerges in all of its richness and dialects in his manuscripts; to the Albanian history, culture, and myth; to the unique wealth of experiences that would otherwise be unseen and unaccounted for among Western audiences. For instance, Kadare’s debut novel, General of the Dead Army (1963), captures the daily life of communist Albania with reminiscences of World War II history. Chronicle in Stone (1971) is situated in Kadare’s hometown of Gjirokastra and the peculiar neighborhood culture that emerges in that insular setting. Later works like Broken April (1978) take us through highland Albania with its blood vengeance and medieval law codes, while The Three-Arched Bridge (1978) transports us into medieval Albania, prior to its Ottoman occupation, allowing Kadare to muse about what Albania might be like if there had never been an occupation. Throughout his novels, Kadare inscribes Albania and Albanian literature onto the canvas of world literature, exploring up close the intricacies of his culture but always connecting them to a broader cultural trend or movement.

In this sense, Kadare is a fundamentally Albanian writer who also fundamentally embodies world literature. As we think about world literature, it is worth recalling here a letter to Johann Eckermann, famously written by Goethe in 1827, that defines world literature: “I am more and more convinced that poetry is the universal possession of mankind,” he writes, “revealing itself everywhere and at all times in hundreds and hundreds of men. . . . National literature is now a rather unmeaning term; the epoch of world literature is at hand, and everyone must strive to hasten its approach.”[i] As Albania’s greatest and best-known writer, Kadare embodies the very essence of how world literature is defined by Goethe. This consciousness, or at least yearning, of belonging to one’s intimate setting but also to something much greater is apparent throughout Kadare’s oeuvre.

While recounting the beginnings of his writerly career in conversation, Kadare recollects a moment when even as a young boy in Albania he began by copying out his translation of Shakespeare’s Macbeth by hand. This initial gesture of connecting his writing to something greater is then reflected in Kadare’s own later essays about world literature. In essays that I have translated about Shakespeare, Aeschylus, and Dante, Kadare discusses the influence of these authors on his own writing, but he also defines them as world authors who channel world phenomena in their works.[ii] Kadare connects the high art of these canonical authors to the unvarnished daily drama and performativity inherent to marital and funerary rites among individuals living in the Balkans. Even though he writes about a time when the Balkans were not producing proper literary texts, by looking at both oral literature and local customs, Kadare traces the foundations of literariness in Albania, taking what might be construed as a literary periphery and a small literature and connecting it to the same creative wellspring that gives rise to major world literature.

In this intentional connection of Albania to Shakespeare, by equating the work of an established literary genius with the genius of many faceless Albanian oral rhapsodists, Kadare situates Albania on the map of world literature.

In an essay on Shakespeare, “Hamlet, the Difficult Prince,” Kadare ties the figure of Hamlet to the Balkans and traditions of blood vengeance in the region—seeing the Danish prince as someone who could be born in this area or created by an oral rhapsodist from the region. In this intentional connection of Albania to Shakespeare, by equating the work of an established literary genius with the genius of many faceless Albanian oral rhapsodists, Kadare situates Albania on the map of world literature. Moreover, he constructs an alternative realm and an alternative Albania and the Balkans—as bound up with and thriving in the realm of literature and literary systems, even if reality and political systems brought only loss and defeat. Whereas Albanian blood vengeance and Albanian political realities, like Enver Hoxha’s regime, were nothing short of devastating in real life, in literature they could become the foundation for the genre of tragedy or for sophisticated, dystopian high modernism like that apparent in Kadare’s writings. This dualism between the real and the literary, between the world and literature, which came together in Kadare’s pursuit of world literature, is, I would argue, essential to how we should understand him both as a writer and public figure.

There is a brief passage in Kadare’s Neustadt Prize acceptance speech that I would like to highlight because I believe it also brings up this important duality between the world and literature. “To believe in literature means to believe in a higher reality,” writes Kadare. “To believe in literature means that that your country’s dark regime seems pale compared to the majestic literary funerary rites. To believe in this art means you always know that the government which dominates you, the police that surveil you, that the parliament, the bosses, the administration, tyranny itself, are a passing nightmare, dead matter, compared to the great order of which you have become initiated as a member” (WLT, Winter 2021, 47–48). These lines reflect the ways in which Kadare as a writer used the alternative, magical world of literature as a way both to elude the horrors of the real and to give them new form and new meaning in art.

Kadare as a writer used the alternative, magical world of literature as a way both to elude the horrors of the real and to give them new form and new meaning in art.

For instance, within the bounds of Kadare’s art, Enver Hoxha’s totalitarian and repressive regime in Albania, although it could not be denounced outright—because such a denunciation would cost the author his life—could become something else entirely. In this case, it became the basis for Tabir Saraj, the palace of dreams from the 1981 novel The Palace of Dreams. Tabir Saraj is the center of an irrational and arbitrary authoritarianism whereby individuals are imprisoned for no good reason other than a dream omen that indicates future crimes, and individual freedoms are encroached upon to the point where even the subconscious is laid bare as dreams are collected by the state police. The only freedom possible in The Palace of Dreams is that of art, which allows the writer to capture the distortion of the regime through the controlled and crafted lens of artistic refraction. It was precisely the ability of literature to make room for this refraction that then enabled unique expression within its distorted realm and idiom, and that gave an author like Kadare a unique, unexpected, and ultimately life-giving freedom. It was not life that gave Kadare art, but it was art that gave him life, and some freedom.

The author has drawn his fair share of ambivalence and controversy over the years, largely as a public figure in Albania: for not speaking out in one way or another, for not being a certain type of dissident, for not always being an activist public figure. He’s eighty-four years old, but such expectations are natural given the dearth of credible and objective voices in Albanian public life, both during communism and now. I have always found these expectations as not entirely consistent with Kadare the writer and his artistic philosophy. His art exudes the need to use art and artistic refraction and the escapism of art to construct psychic defenses against reality. The world of dreams and myth or the warped lens of a highland society helped the author construct a type of magical realism that was essential to his ability to create and survive as an artist despite the artistic pressures to conform to socialist realism.

At the same time, this world becomes the only path for the author to respond to the terrors of the present. It is in its ability to capture authoritarianism and in the process discredit it that art becomes a political weapon, that it can fight back against political regimes but do so through its own, often ambivalent devices. But this fight, this response is not one that unfolds loudly on the streets or even in the newspapers; it is, for Kadare, something that transpires within the layers and poetics of art. Because, within Kadare’s artistic universe, the moment that art mirrors the headlines of newspapers and the artist’s voice speaks linearly to the present, not only does the artist run the risk of being erased within regimes like Hoxha’s Albania, but the art starts to conform to socialist realism and the political expectations of various nondemocratic regimes.

To give an example, following the 1998 crisis in Kosovo, when Slobodan Milošević’s troops ethnically cleansed Kosovar Albanians followed by the 1999 NATO bombings of Serbia, Kadare wrote his piece Three Elegies for Kosovo. Rather than directly addressing the immediate tensions of the present, this narrative was focused on the original 1389 Battle of Kosovo, as Kadare meditates on the needless tensions that arose among Balkan peoples on account of the Turkish occupation. The underlying message—that more unites Serbs and Albanians than divides them—was a valid and conciliatory one, but it was delivered through the distant prism of the past rather than directly addressing present conflicts. Although everyone would have sought a tendentious message from Kadare, that was not what he was able to provide, because his whole profile as a writer was built upon resistance toward ideological tendentiousness, which is not to say that Kadare does not have his own ideological blinders, but they’re inherently his and not externally imposed.

I will close on a personal note. As a first-generation Albanian immigrant in the United States, with all the identity fragmentations that entails, I have come to deeply appreciate both what is Albanian and what is worldly about Kadare’s art. In its ability to speak to the universal through the particular, and to speak to the particular only through the universal, this body of writings has provided one of the single most profound points of identity cohesion for me. In my study of works like The Palace of Dreams and in translating Kadare’s writings, I felt my Albanian past, and the world of literature that I devoted myself to as a scholar, come together. Kadare speaks to history and to the present only from the vantage point of a great writer, and it is this vantage point that the Neustadt Prize celebrates, and it is on account of this vantage point that his words will live past the present and speak to people all over the world and be read for many more decades and centuries to come.

Even if the author is not a proper dissident, which he has never claimed to be, one can never read The Palace of Dreams and not celebrate the perpetual testament to the freedom of imagination that is Kadare’s work.

As an Albanian abroad, I’m grateful for his art. It has returned me time and again to Albania, to my grandparents’ generation—a generation of brilliant and industrious people whose lives were spent working hard and working creatively for very little money, and who, despite their best wishes, were left with very few tangible outcomes for all that labor. Kadare’s work, his great world literature born of a time of terrible oppression in Albania, memorializes that generation and their losses. Even if it does not directly touch on the losses, even if the author is not a proper dissident, which he has never claimed to be, one can never read The Palace of Dreams, with its piercingly brilliant exposé of a totalitarian system seeking to strip human beings of their freedom and imagination, and not celebrate the perpetual testament to the freedom of imagination that is Kadare’s work.

In living and writing, and in leaving behind the kinds of literary masterpieces he has created, Kadare resisted Hoxha’s regime. I am grateful his work was awarded the Neustadt Prize.

University of Kansas

[i] Quoted in David Damrosch, What Is World Literature (Princeton University Press, 2003), 1; reviewed in WLT, May 2004, 95.

[ii] See Ismail Kadare, Essays on World Literature: Aeschylus, Dante, Shakespeare (Restless Books, 2018); reviewed in WLT, March 2018, 89.