Our Revenge Will Be the Laughter of Our Children

What is it about the revolutionary that draws our fascinated attention? Whether one calls it the North of Ireland or Northern Ireland, the Troubles continue to haunt the land and those who lived through them.

Séanna Walsh’s face is impassive. That’s the first thing you notice about him, after his imposing bulk of a body. It appears he has spent a long time to compose his face, to harden it, until it became hewn, glacial. Beneath it, you sense unplumbable depths. He was just sixteen years old when he went to prison for the first time in 1973, as a Volunteer in the Irish Republican Army, long before his black hair started turning ice-white. During the next twenty-five years, he’d spend over twenty years in serving three sentences, until he was finally released under the terms of the Good Friday Accords.

Still, Séanna hasn’t lost his sense of humor. Our delegation of students and faculty from John Carroll University have just arrived to Belfast from America on an overnight flight, bleary-eyed, and now find ourselves at Malone Lodge Apartments hosting Séanna and his comrade Jim Gibney, prominent activists in the Republican movement, party members of Sinn Fein.

Leaning in on the rickety chair we’ve set up for him, Séanna asks us, “Have you had any rest yet?”

“None at all,” I say, hoping the legs of the chair don’t give out underneath him.

“Then you’ll get some during this talk,” he quips, leaning back.

We laugh, and the ghost of a smile seems to pass over his face. Perhaps he’s softened a bit, since I first met him eight years before, but it’s hard to tell.

Just behind him the bay window opens up, and the city is spread out below, all the way to the Black Mountain that stands at its far edge.

During the Troubles, that thirty-year descent into political violence that led to the deaths of thousands and tore the country apart, Séanna and Jim believed themselves to be revolutionaries in a war for freedom from British rule. Today, twenty years after the 1998 peace accords, even the name of this country is still contested. For the Protestant Unionists and Loyalists, we are now in Northern Ireland, part of the United Kingdom. For our guests, staunch Republicans, this is the North of Ireland: the last remnant of Eire still under British control. It depends on your point of view, what name you were willing to stand by, or even kill or die for. Séanna was prepared to do all three.

Now, during peacetime, the question is more mundane, and perhaps more difficult: What are you willing to live for?

Now, during peacetime, the question is more mundane, and perhaps more difficult: What are you willing to live for?

Since 2011, with the assistance of Raymond Lennon, I’ve been coordinating study tours on the peace-building and conflict-transformation process in Northern Ireland for John Carroll University, meeting with locals who lived through the tumult of the Troubles and have come out on the other side of violence. Séanna and Jim have been stalwarts of our program, crucial inputs in a complex array of perspectives. I think of them as a pair, since every time I’ve met them, they’ve been together.

Perhaps it’s because they grew up together in a Catholic enclave of Protestant East Belfast known as “the Short Strand.” The little beach. The Short Strand, pronounced here as “strahned,” was an island stranded in the middle of a sea of Loyalism, and those who grew up there knew what it meant to look out for your own.

Séanna’s large and quiet presence fills the room. When he’s handed a cup by one of the students, he frowns. “This tea is cold!”

Karly, the student, blanches, wordless, horrified. She’s failed at her first job, making what they call a spot of tea. She just couldn’t figure out when the electric teapot had come to a boil.

Walsh gets up and heats it up himself, mumbling a half-joke about the service around here.

In the margins of my notebook, I’m scrawling potential titles for the name of our meeting: Tea with Terrorists? Victims of IRA violence would call them murderers and worse. Séanna and Jim won’t say what they have done, because, twenty years after the peace accords, they still could go to jail if those words or old crimes came to light.

I wonder what it’s like to carry those secrets in the plain light of peacetime.

It’s not fair to just call them terrorists. Look at them: Séanna and his gray-white hair, looking like someone’s tough uncle, Jim and his piercing eyes and stylish frames, resembling a college history professor. They are like all of us, with complicated lives and reasons for what they have done or what they have failed to do.

But the truth is that I’m also a little afraid of them. I know their ferocious commitment; I can see the fierceness in their faces, and also the hurt.

How long does it take for a warrior to come home? In The Odyssey, after fighting in a decade-long war, Odysseus takes ten years to get home. In my favorite reading of the epic poem, psychiatrist Jonathan Shay proposes that the journey is a powerful allegory for the painful and circuitous route that every soldier needs to take in order to come home again. Working with veterans at the VA, many of whom struggled with PTSD and other emotional stress from combat, Shay comes to see each episode—from the poppy eaters to his long stay with Circe—as metaphors for the ways that soldiers rely on narcotics or sex to try to numb the pain.

Psychiatrist Jonathan Shay proposes that The Odyssey is a powerful allegory for the painful and circuitous route that every soldier needs to take in order to come home again.

A Republican and lifelong activist who also spent some of the Troubles in prison (despite never having been convicted), Jim Gibney is small and voluble, with intense blue eyes shining through his horn-rimmed glasses. He’s the thinker, launching into his narrative of the North as a colonial problem, something that’s been going on for “many centuries” but only “became armed in the last fifty years.”

“I didn’t like prison,” Jim admits, as if embarrassed to say it in front of his friend and us. “In essence, though,” he pauses, “it was education. Comradeship.”

He leans forward, trying to find the words.

“I was transformed from being a boy who wouldn’t have read a book to one who was a custodian of books.”

When Séanna first went to prison back in 1973 for a failed bank robbery, he was no ordinary criminal seeking easy money. He was funding the Provisional Irish Republican Army. Séanna got involved in the movement when Loyalists killed his friend Patrick McGrory. Because history has a way of repeating itself here, it also happened to be in the same neighborhood that the B-Specials, a particularly vicious arm of the security forces in Northern Ireland, had murdered his grandfather fifty years earlier. All this history within arm’s length of where Séanna and Patrick would have played on the streets as children.

In prison, Walsh got an education that his public schooling had never taught him—about Irish history, politics, and language. What began as anger turned into ideology.

“The British couldn’t kill the fish,” Séanna says, “so they tried to pollute the sea.”

By age twenty, Séanna was appointed the IRA commanding officer in the Crumlin Road jail and was considered an old-timer.

As the sides entrenched, the Troubles got uglier—with all sides committing greater and more brutal acts of violence. The IRA and other paramilitary organizations on both sides of the conflict engaged in regular bombing campaigns in which civilians frequently died. They even terrorized their own communities, using kneecappings, banishment, or even disappearance to stop collaborators or criminals from interfering with the struggle. With the complete breakdown of local policing, paramilitaries functioned as law enforcement. If the person’s crime were bad, they would get a “kneecapping”—that is, a bullet to the knee. But if the crime was egregious, they’d get a “six pack”—shots to both knees, ankles, and elbows. There were nearly as many kneecapping victims as there were deaths during the Troubles.

At the same time, the Shankill Butchers, a rogue gang affiliated with the Ulster Volunteer Force, terrorized Catholic neighborhoods by randomly torturing and murdering civilians in the late 1970s. Their crimes were among the most shocking of the Troubles. While the IRA could be seen as selecting its attacks against what they deemed were British military targets, the Butchers went further by randomly picking Catholics off the streets and subjecting them to the depths of human cruelty—pulling out teeth, beatings, and cutting throats all the way to the spine.

Ostensibly to restore public order, but also to break the Republican movement, the British government ended the political status of paramilitary prisoners in 1976 through the policy of Criminalization. Then, to crack down on the organizing happening in prison, the British government phased out the use of Crumlin Road jail and the open Nissen huts of Long Kesh prison, replacing them with the H-Blocks of The Maze, isolating the prisoners from one another.

If Criminalization was an attempt to delegitimize paramilitary activity, it only made the paramilitaries resist further. The IRA found new ways to organize and resist. Landing in prison a second time on weapons charges, Séanna participated in the Blanket Protest, begun in 1976 when IRA volunteer Kieran Nugent refused to wear the prison uniform given to him in the H-Block, wrapping himself instead in a blanket. By 1978 three hundred volunteers, including Séanna, had donned the blanket, refusing any accommodation.

“There was no master plan,” Séanna says. “Just a young man who resisted.”

The IRA prisoners were regularly beaten, even tortured, by guards who saw them as enemies of the state and a threat to their Protestant Unionist community. The No Wash Protest soon followed, when police refused the inmates a towel to dry themselves off. After a fight between an IRA volunteer and a police officer, inmates destroyed their cell furniture in protest of the beating. As a response, the guards removed all furniture, leaving only the blankets and mattresses.

The Dirty Protest had a theatrical madness to it, which makes a perverse sense, since it was either the act of men driven crazy or performance artists confronting their audience with an external representation of their condition of oppression.

The Dirty Protest ensued. Prisoners refused to leave their cells to shower or to slop their waste buckets out of the window and instead poured them under the door to flood the halls. In retaliation, the guards would push the urine back inside the cells. At some point, prisoners took to wiping their excrement on the walls of their cells. It had a theatrical madness to it, which makes a perverse sense, since it was either the act of men driven crazy or performance artists confronting their audience with an external representation of their condition of oppression. Maggots were everywhere, and the stench was overwhelming. The visiting Archbishop Tomas O Fiaich reported:

One would hardly allow an animal to remain in such conditions, let alone a human being. The stench and filth in some of the cells, with the remains of rotten food and human excreta scattered around the wall, was almost unbearable. In two of them I was unable to speak for fear of vomiting. Several prisoners complained to me of beatings, of verbal abuse, of additional punishments . . . for making complaints, and of degrading searches carried out on the most intimate parts of their naked bodies.

One film taken inside the prison shows two “blanket men” with long black hair and beards and haunted eyes, wrapped in a robelike blanket. They look like replicas of the 1970s images of Jesus. Yet in that same film, two other prisoners smile at the camera, singing or shouting something that we cannot hear. Despite the stench, the archbishop felt that the spirit of the men was high, as he noticed “Irish words, phrases and songs being shouted from cell to cell and then written on each cell wall with the remnants of toothpaste tubes.”

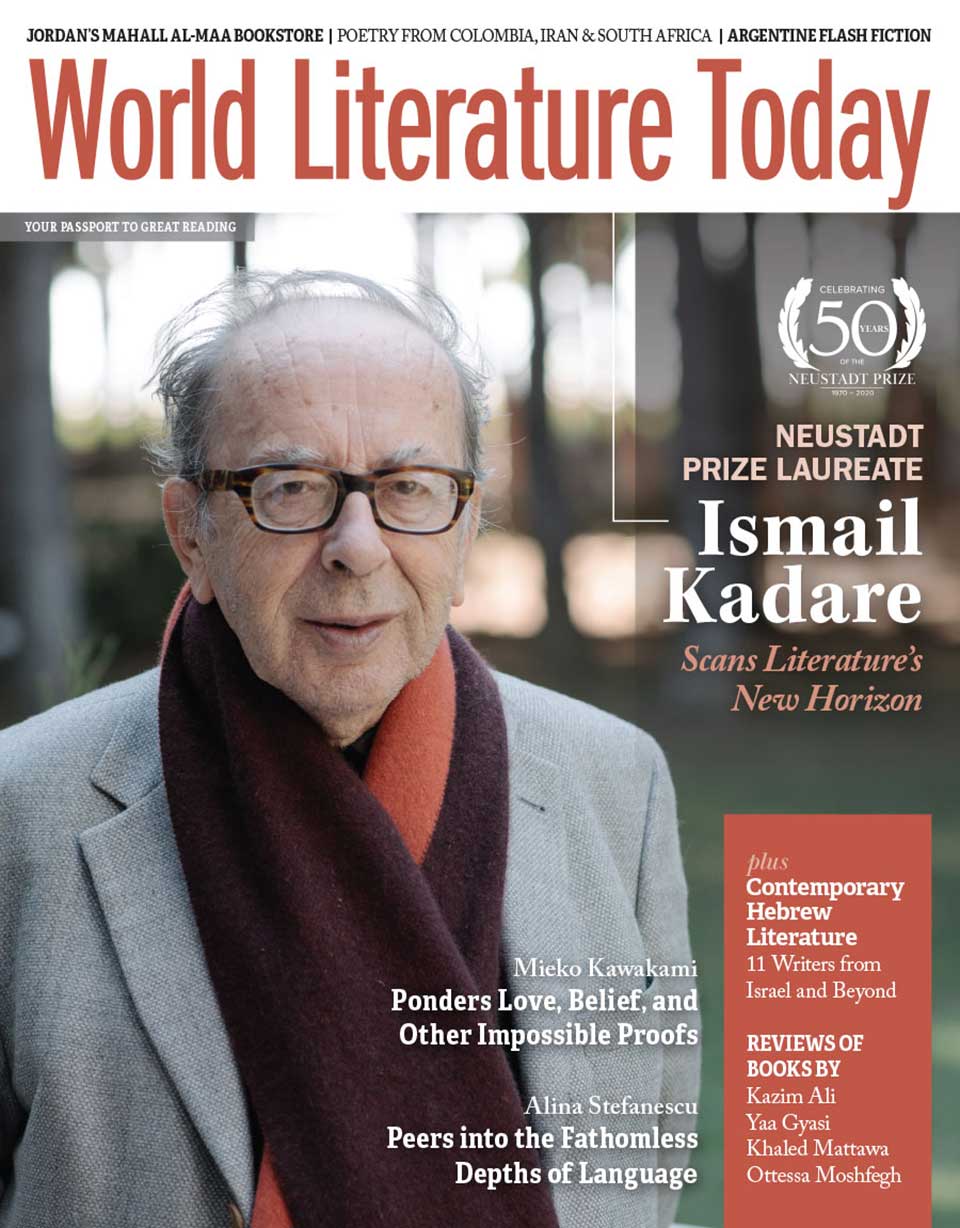

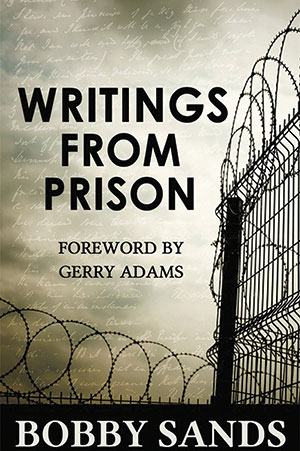

In One Day in My Life, Republican martyr Bobby Sands writes keenly of the daily torments experienced by the prisoners:

[The prison guard] stepped beside me, still laughing, and hit me. Within a few seconds, in the midst of white flashes, I fell to the floor as blows rained upon me from every conceivable angle. I was dragged back up again to my feet and thrown like a side of bacon, face downwards on the table. Searching hands pulled at my arms and legs, spreading me like a pelt of leather. Someone had my head pulled back by the hair while some pervert began probing and poking my anus.

The bitter cold, the stench, the physical and psychological torture of regular beatings, anal cavity searches, and derision were a daily reality for prisoners. But Sands also wrote poignantly of throwing maggots from his cell window onto the yard below to watch the birds gather to feast: “sparrows and starlings, crows and seagulls were my constant companions . . . my only form of entertainment.” He composed One Day in My Life in 1979 on bits of toilet paper that were smuggled to the outside—as were all the “comms” (communications)—in a biro pen refill case that he hid in his cheek or anus and then passed secretly to a family visitor to the prison.

Despite the violence he faced in prison, Sands remained spirited. “I am,” he wrote near the end of his life, “(even after all the torture) amazed at British logic. Never in eight centuries have they succeeded in breaking the spirit of one man who refused to be broken. They have not dispirited, conquered, nor demoralised my people, nor will they ever.”

When British prime minister Margaret Thatcher won election in 1979, she ratcheted up the rhetoric of Criminalization, and the prisoners fought back with a hunger strike in 1980. The strike was for political status but was called off when the prisoners thought they’d won.

Though the British made promises to change the policy in 1980, nothing changed in the prison. So after fierce debate within the Republican movement, another hunger strike began, with Bobby Sands taking the lead position. Other hunger strikers would follow, separated by one-week intervals, to ensure that the pressure would build on Britain.

While in prison, Jim Gibney, in a stroke of genius, decided to put Bobby Sands up for election to the British Parliament in Fermanagh, and a month into his hunger strike, he won. Sands would write in his final diary, begun during the hunger strike: “They won’t break me because the desire for freedom, and the freedom of the Irish people, is in my heart. The day will dawn when all the people of Ireland will have the desire for freedom to show. It is then that we will see the rising of the moon.”

It’s the soaring rhetoric of a Romantic, a Romantic willing to kill and to die.

In advance of our meeting, Jim told Raymond—our program coordinator and a native of Belfast who appears to be on friendly terms with everyone in this country—that they didn’t really want to talk about him again. Bobby Sands. I wondered if it was because it’s too hard to keep talking about the past. But the redoubtable Raymond mentions him anyway, along with Séanna’s association with the Republican icon and martyr who died after sixty-six days on hunger strike, protesting the lack of political status for IRA volunteers in the prison.

Séanna met Bobby in Long Kesh in 1973. He was sixteen, and Bobby was eighteen. Both were released in 1976, and they “went back into active service,” as Séanna calls it. Just a month before, my students and I had been reading Bobby Sands’s final diary during the hunger strike, and Séanna is mentioned in the first pages.

“The thing about Bobby,” Séanna says, looking into the distance, “was that he was just an ordinary guy. What really brought about the difference was the crucible of the H Blocks,” the prison constructed to house and isolate political prisoners.

Séanna pronounces the H like “haitch,” one of the only ways to distinguish Catholics from Protestants. It became a way for street thugs to test a stranger, to see whether they were worthy of freedom, a beating, or worse. Quite literally, it was said that Loyalists (or was it Republicans?—the story differs depending on the speaker) would carry a piece of paper with an H on it and ask their potential victim to pronounce it. That, or say the Hail Mary. Your answer could spare or end your life.

When we first met him seven years ago, when talking about Sands, Séanna had to wipe away the wetness from his eyes, a sudden thaw, his impassivity cracked. This time he stays far from the hard part, skirting the shores, saying vaguely, “We’re living with the legacy of that whole period.”

After seventeen days, Sands could no longer write in his diary. He kept asking for poetry to read.

During the strike, enormous pressure came in from the outside—from the Catholic Church, from family members—but Bobby Sands held fast. He had an iron will, total commitment. After seventeen days, he could no longer write in his diary. He kept asking for poetry to read.

Thirty days, forty days, fifty days. Sixty days.

Jim was the last person to see Bobby before he died in the prison hospital, and as he recalls it, his voice softens to a whisper.

Bobby’s mother and sister were around his bed when he arrived. Bobby was blind at this point, having lost his sight due to the extreme effects of starvation.

“‘Is that you, Jim?’ he asked. I said yes. He gave me his hand and I took it. He said, ‘Tell the lads I’m hanging in there.’”

Neither of them wants to go farther.

In 1981, after Sands’s death, Séanna would become the officer-in-command of the IRA prisoners. He was back in prison for a third time, arrested for possession of rockets in 1988. After the Good Friday Accords allowed for the release of prisoners, he was the IRA representative selected to read the 2005 IRA statement to announce that they had given up the armed struggle in favor of a political one. In the bluish video, you can hear birds singing and a baby crying now and then in the background as Séanna sits in front of a green flag and reads a written statement, his face drawn and his voice direct but almost flat in affect.

I kept wondering about that baby, the life outside the frame of that camera, where someone had to mind a crying child and where birds sing as if there were no war.

I kept wondering about that baby, the life outside the frame of that camera, where someone had to mind a crying child and where birds sing as if there were no war.

It’s been said that if the Troubles had been fought by films, the Irish would have beaten Britain long ago. It’s true that the movies depicting the Irish struggle have been enormously popular and often artful. Yet it’s also true that in the films of the Troubles, the IRA often play the foil. They begin as daring radicals, whose courage and audacity seem attractive and almost mythic, but later they reveal themselves to be cruel beyond any normal human measure. I watched these films with fascination—furious at British oppression and intransigence, in awe of the commitment of the IRA, and repulsed by the lengths they would go for a United Ireland.

In the film In the Name of the Father (1993), Gerry Conlon, a petty thief, is convicted of an IRA bombing he didn’t commit. Based on actual events, Conlon, his father Giuseppe, and others—known as the Guildford Four and the Maguire Seven—are swept up in a British crackdown after the Guildford pub bombing in 1974. Tortured into false confessions or railroaded by false evidence, all of them wind up in prison for many years. During the film, Conlon becomes infatuated with a fellow prisoner and IRA member, Joe McAndrew, whose charisma, political vision, and muscle seem to be the opposite of his timid milquetoast of a father. McAndrew is a man who can whisper to the baddest Loyalist prisoner that he knows where his family lives and have that man announce to all that McAndrew is all right by him.

However, Conlon’s awe changes when he witnesses McAndrew nearly burn the prison warden to death in an act of pure revenge. Watching the film, the viewer is drawn in by McAndrew, with his revolutionary discipline and ability to move people to action, and then sickened by him, as Conlon is later on. The hero, it turns out, is Conlon’s sweet and simpering father, whose devotion to his wife and to his cause—writing letters to his British lawyer—demonstrate the durable heroism of ordinary faith.

Even so, what is it about the revolutionary that draws our fascinated attention? Is it the profound courage and single-mindedness of commitment? The ability to stretch oneself beyond the boundaries of normal human morality?

Séanna and Jim. Who’s minding whom? Every time I’ve met one, I’ve met the other, as if they were two parts of the same person. In the room with us, both men cross their legs, left over right, rhyming. When one stops speaking, the other picks up. Jim gestures with his hands—fingertips touching, then dancing, then, when he stops speaking, crossing them over his chest. When either one stops speaking, he scrolls through his phone, as if he’s managing two realities at once.

Jim sets up the colonial context of Ireland, the story of eight hundred years of British oppression, the red-meat-and-potatoes narrative of Republicanism, which led to their being dragged into the “war”—their favored term for the Troubles.

So often, former paramilitaries tell their story as if they were caught in conditions that gave them no choice but to fight. Séanna picks up the thread and turns it in another direction: “I’ve never felt that I had no choice. I always felt that I was the author of my own destiny.”

That’s what draws my fascination toward the revolutionary. That, despite holding fiercely onto their narrative of victimization, they choose not to remain passive victims. That in resistance, they become captains of their fate.

Yet at what cost—not only to the victims of their violence, but also to themselves?

In college, when I first got an inkling of the Troubles, I’d been reading the poems of W. B. Yeats in class. Despite the fact that he was part of the Protestant ascendancy, Yeats loved Ireland and the romance of Irish culture and nationalism. Yet something changed in him when, on Easter Sunday in 1916, the Irish Republican Brotherhood rose up and declared a free Irish Republic, taking over the general post office in Dublin and other sites around the country. The uprising, broadly opposed even by the Irish people, was brutally crushed by the British, and nearly all the leaders were executed. The severity of punishment inflamed Irish nationalism and would lead to the War of Independence.

In his poem “Easter 1916,” Yeats measures his own fascination-repulsion reaction to the Easter rebels, many of whom he knew personally, in his powerful refrain: “All changed, changed utterly: / A terrible beauty is born.” Yeats saw the power of that sacrificial act of revolutionary violence, how it changed so much in his benighted Ireland. It was terrible, in both senses of the term: awe-inspiring and awful. Yet it was also beautiful.

Despite his aristocratic background (which he shared with many of the leaders of the rebellion), Yeats could see that they’d chosen to give up the “meaningless tales” that they’d shared at their social clubs to become their own story. Yet he’s haunted by what they’ve given up in the process of their revolutionary ardor:

Hearts with one purpose alone

Through summer and winter seem

Enchanted to a stone

To trouble the living stream.

The horse that comes from the road,

The rider, the birds that range

From cloud to tumbling cloud,

Minute by minute they change;

A shadow of cloud on the stream

Changes minute by minute;

A horse-hoof slides on the brim,

And a horse plashes within it;

The long-legged moor-hens dive,

And hens to moor-cocks call;

Minute by minute they live:

The stone’s in the midst of all.

Too long a sacrifice

Can make a stone of the heart.

Yeats wonders whether the rebels became stones in the living stream, forgoing their essential humanness in this violence. Such sacrifice, the sacrifices that they made to rebel—did it turn their hearts to stone? did they lose their humanity?

This is the question we cannot know, those of us who have not gone into the shadows and risked everything personally and made decisions that could lead to death. But I think of Bobby Sands feeding birds outside his prison cell window with the maggots from his own offal, and of him reading poetry while starving himself to death.

Perhaps it’s not fair, director Jim Sheridan’s depiction of the revolutionary in In the Name of the Father—which is, after all, the usual representation. It reflects bourgeois values. We, well-meaning liberals, pay lip service to resistance but advocate nonviolence from the safety of middle-class privilege, into which we can retreat after the end of any activism. So many of us are simply unable or unwilling to make the sacrifices necessary to make radical political change.

In an interview about the film The Crying Game, a stunning film about the Troubles and the possibility of self-transformation, Sinn Fein writer and Republican activist Danny Morrison laments that the film unfairly depicts the IRA. To Morrison, no film had captured their humanity: “Why isn’t there a film made which portrays the IRA as flawed . . . but still emerging at the other end with their humanity intact?” The two main characters “are depicted as psychopaths. . . . They are all fanatics. To me, that’s unreal.” Perhaps he’s right. But there’s an ache in his wondering, as if that journey back to humanity is a long one.

Morrison himself is known among Irish poetry circles for his notable meeting with Seamus Heaney on a train. In Heaney’s telling, Morrison tried to hector Heaney into writing a poem for the prisoners engaging in the Dirty Protest and later the hunger strikes. Heaney refused to cave to the pressure. In “The Flight Path,” Heaney writes that Morrison demanded a poem: “‘When, for fuck’s sake, are you going to write / Something for us?’ / ‘If I do write something, / Whatever it is, I’ll be writing for myself,’” he replied.

Morrison remembers it differently, as a cordial encounter that ended in a handshake: “In Stepping Stones [Heaney] says that he felt he was being ‘commanded,’ and for that reason changed his mind.. . . I find that explanation hard to reconcile with the fact that after our conversation we parted with a handshake; he gave me his address and telephone number and agreed to read the poetry of Bobby Sands,” which included criticism of artists and poets for their silence in the face of oppression and which Sinn Féin later published.

We stand in the gulf between the civilian and the warrior, between the poet and the revolutionary.

Did Heaney exaggerate his rebellion against the rebels, or did Morrison minimize the threatening impact of being approached by a member of the IRA to ask for fealty? We’ll never know. We stand in the gulf between the civilian and the warrior, between the poet and the revolutionary.

Back in Belfast, sometimes Jim and Séanna’s back-and-forth testimony in our little apartment room feels a little staged, as if they are performing for us. Maybe that’s because they keep switching between talking and looking at their phones. There is a rote quality to it, as if they’ve heard everything the other has said or are acting in a play whose script is not yet completed, the script of Republicanism and its unremitting quest for a United Ireland.

As if to punctuate a previous point, Séanna lifts up his phone to us and says, “I hope you don’t think I’m uneducated, scrolling through the phone. I was looking for this picture that someone posted on Facebook.” He turns the screen toward us. It’s a bus whose route reads “#93 Bobby Sands Street,” and it’s from Nantes, France.

Raymond comments on the international reach of Bobby Sands, including in Iran. Séanna picks up the idea, noting that Bobby Sands Avenue in Tehran came about when some local revolutionaries put a homemade placard over the sign for Winston Churchill Avenue. Later, the authorities made it official. The street was the site of the British embassy.

“For a while,” Séanna said, glee radiating through his usually impassive face, “all correspondence to the British embassy had to be addressed to Bobby Sands Avenue.” The British actually built a side street with a new name to create a new address for the embassy, just to avoid the humiliation.

(Later I’d learn that, thirty years before, during the burial of three IRA volunteers in Milltown Cemetery, a rogue Loyalist named Michael Stone attacked the funeral crowd with grenades and pistols. Shrapnel tore into Séanna, who was driven to the hospital in a funeral hearse. He’d never mentioned this attack, in all the years we’d been meeting with him.)

After a pause in the back-and-forth between Séanna and Jim, I begin my question: “You spent over twenty years in prison—”

“—Twenty-one,” Séanna interrupts. As if he’s counted every day. And keeps counting them.

“What was it like to be released, after such a long time? How did you manage? What was it like to be freed?”

“Have you ever read L’Étranger? The novel by Camus? That’s how I felt. An outsider.”

Séanna squints and looks out into the distance over Divis Mountain when he speaks. Divis means “black” in Irish, as the sun falls behind it every night.

“I felt numb. It has dulled somewhat as I’ve gotten older.” He pauses, searching for the words. “In prison, I thought freedom was simple, was easy. It meant being out of prison. But I was naïve. Whenever I came out of prison, I was as dedicated as I was as a sixteen-year-old. But the context has changed. There is no longer an armed struggle. I traveled the length of the country to convince comrades to lay down their arms.”

It helped, he said, that he had a strong wife, also a Republican, who raised two daughters while he was in prison. I wonder what they might say, about what it was like to have a husband and father whom they barely knew outside of prison, who was absent more than he was present. I wonder what his wife would say about her side of the struggle, what it was like at home.

The Republican movement had a place for him when he got out, which was critical because he couldn’t get work otherwise.

In some ways, he’s like the several thousand other IRA Volunteers who walked out of prison after years behind bars, blinking in the sudden light of freedom, trying to find their way in the new, post-Troubles reality. They did their national service, as it was called, but so many are the walking wounded, suffering from alcoholism and drug addiction, trying to cope with all kinds of pain. The descendants of Odysseus, not yet in Ithaka. Still trying to get home.

Tony, one of our students, begins a question: “Bobby Sands said that our children’s revenge—”

“—Our revenge,” Walsh corrects, almost barking, “will be the laughter of our children.”

It’s important for him that we get things right, that the record is clear. Twenty-one years in prison. Sixty-six days on hunger strike. Our revenge will be the laughter of our children.

Of all the words I’ve read and heard about Northern Ireland, these are the ones that have haunted me most. Painted prominently on the Bobby Sands mural on the Republican enclave of Falls Road, Sands’s words encapsulate the paradox of the Republican struggle, a struggle that has led to much blood in the name of a free and united Ireland.

The struggle, according to Sands, was the means to create a better life for their children. So that their children wouldn’t have to live the way that they had to live. Isn’t that every parent’s wish, that our children be spared our particular hardships? In this land, when so many suffered oppression and violence for so long, that natural parental feeling was even more pronounced. So that their faces might be free from the ice of the Troubles, to laugh or to cry, without fear of what it might mean to open up that way.

Perhaps this is why Séanna keeps moving himself, keeps telling his story—that it may be different for his children, or his children’s children.

As I complete this essay, I look up Séanna online to find something I didn’t know about him, something that might reveal more of his mystery.

He’s on Facebook, I discover, and I click on the link.

In the profile photo, he’s sitting in a plush chair, an infant wrapped in a blanket and lying wide-eyed across his arms, with a look of animal seriousness that some babies wear. Right next to them, a vivacious redheaded toddler straddles the back of a couch. He and the toddler squint similarly toward the camera. That’s a squint I know, the squint of Séanna thinking, unconsciously disagreeing, with the glare of a world that never seemed to be gentle or fair or free. Yet the shapes of their mouths—it’s uncanny—are nearly identical, both parting in a smile.

University Heights, Ohio