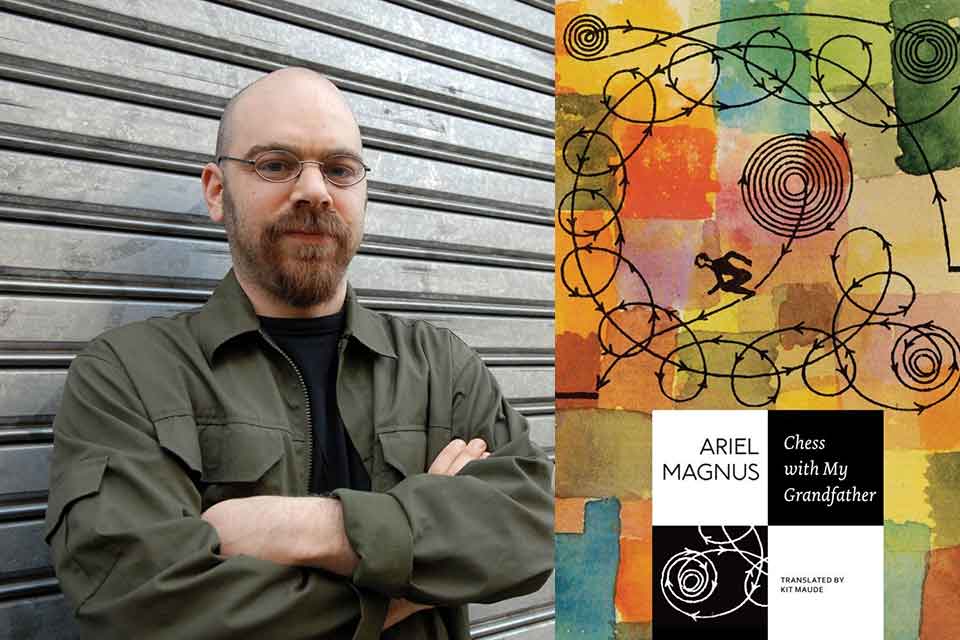

On Writing, Translation, and Other Distorted Mirrors: A Conversation with Argentine Writer Ariel Magnus

Argentine writer Ariel Magnus is the author of well over a dozen books in different genres. His novel Chess with My Grandfather is forthcoming from Seagull Books. Three of his microfictions from Seré breve (I’ll be brief) are published in this issue. In this conversation, Magnus speaks with his English translator, Kit Maude, about his grandparents, literary provincialism, and translators as writers’ closest readers.

Argentine writer Ariel Magnus is the author of well over a dozen books in different genres. His novel Chess with My Grandfather is forthcoming from Seagull Books. Three of his microfictions from Seré breve (I’ll be brief) are published in this issue. In this conversation, Magnus speaks with his English translator, Kit Maude, about his grandparents, literary provincialism, and translators as writers’ closest readers.

Kit Maude: A brief glimpse of your bibliography shows that your work varies greatly, often quite wildly, from book to book—something I’ve experienced firsthand as a translator over the years (I’ve been known to double-check that I am indeed dealing with the same author). Is this a conscious decision on your part?

Ariel Magnus: Italo Calvino, whom I admire, used to hear that comment too. So I take it as a big compliment. And, yes, I do like to think of each book as an independent world, with laws that don’t necessarily have to have much in common with the other ones. But there are themes or ideas I repeat in more than one novel, always trying to fail better. I like to surprise myself while writing, perhaps because it’s the easiest way to fantasize that the texts have a minimal degree of originality. I think change, striving for something new (even knowing that it can only be wishful thinking), is a kind of honesty: what you should at least aspire to when you do something you care about. But perhaps it’s just an instability of mind, an insecurity of style. I admire many writers who allow you to read one book after another as though you were just moving from room to room in the same house. It gives you a wonderful feeling of coziness.

I do like to think of each book as an independent world, with laws that don’t necessarily have to have much in common with the other ones.

Maude: Which leads me to my next question: in spite of the variety of your work, do you see yourself as writing in a tradition? One obvious common thread is formal and thematic experimentation—I was going to mention Calvino, but I’d also hazard a guess at some rioplatense influences: Borges, perhaps more particularly Macedonio Fernández (who makes a cameo appearance in Chess with My Grandfather).

Magnus: I read Borges, Macedonio, and Calvino wildly, among so many other authors, but I wouldn’t dare to mention my writing in the same breath. There are specific books where I’ve had certain authors in mind while I was writing them, but it’s more like a game, a magical—and quite irreverent—dialogue. To love some authors, or quote them and even try to emulate them, doesn’t mean, of course, that your writing measures up to them, except maybe in your fantasies. Anyway, I try not to think about literature that way but to just do it. At the same time, I’m very aware that there is a vast history behind every word I use. The question about traditions is something the future will resolve; we’ll see if my books live that long. I wouldn’t bet on it.

Maude: Being a little coy, I see. But I’m going to persist because I’m interested in the process by which your books come about. For instance, what possessed you to write Seré Breve (I’ll be brief), the collection from which the texts in WLT came? Did you wake up one morning and decide you were going to write a hundred hundred-word stories?

Magnus: Coy? When you confront me with Borges, Macedonio, Calvino? Aware of my status and limitations, I would say. Anyway, this is how I work: I’m always having ideas. For stories, characters, phrases, structures, titles, puns . . . I write them all down, always with the feeling that this is the beginning of something big, the path that’s going to lead me to THE book. When I finish something, I return to my notes to decide what to write next. Then I realize that not all of those ideas were really very big, and only a very few, just one usually, is going to be of use for an entire book. This happens year after year.

But one day, I noticed that I had a lot of very small ideas, and began to write some of them on their own terms. After I’d done a few, I noticed that they were all about a hundred words long, and because I like fixed structures and I work better when I have a book in mind, I said to myself: why not one hundred stories of a hundred words each? So I wrote Seré breve and, meanwhile, another called Minucias (Minutiae). I now dream of writing ten of these booklets. Adding, of course, a final story to the collection.

Maude: Oh, that would be fun to translate . . . the Magnus Omnibus!

Chess with My Grandfather also began with a notebook, but in this case one that had belonged to your grandfather, which you then combined with what I now realize must have been one of the entries in your ideas notebook, about the World Chess Championship of 1939.

Magnus: My grandfather, who died before I was born, kept a real diary. It begins in 1935, when he, as a Jew in Hamburg, knew that he was going to have to flee the country. I found it by chance several years ago and wrote a nonfiction (unpublished) book about it. Years later, editing a posthumous novel by Ezequiel Martínez Estrada, I came across the World Chess Championship of 1939 and thought: this would be the perfect setting to put my grandfather into action. Why? Well, in 2006 I published a nonfiction book about my grandmother (from the other side of the family) and always regretted not having made her into a character in a novel. So this was a kind of vengeance.

Maude: You still could! Obviously, Jewish heritage, culture, and history feature heavily in both grandparent books, but they also appear regularly in your other work. Is that a conscious decision? I also have a theory that you’re interested in the idea of diaspora . . .

Magnus: Jewishness appears quite a lot, it’s true. Mostly because of the jokes. We Jews are a wonderfully vast repository of humor. And it’s also a Weltanschauung I’ve learned from my family, something comfortable to grasp hold of. Perhaps too comfortable? In any case, the resource is there and I make use of it. But I don’t feel that Jewishness and the like are the subjects of the books where I use that heritage. As a theme I find it quite boring, to be honest. The same with diaspora, I guess. Although I would say that I’m interested in the idea of migration in general.

Maude: Eeep! A good thing your grandparents can’t hear you. . . . Which Jewish writers/artists/thinkers come to mind especially?

Magnus: Well, I don’t really know what Jewish literature is. Max Brod? And I don’t like to make that religious difference, either. I did enjoy Scholem’s books on the Kabbalah a lot, though.

Maude: And what interests you about migration?

Magnus: What interests me most about migration is, I guess, that it forces you to think about your own culture. A new culture coming to yours is a kind of distorted mirror, in which you can see all your deformities. And the other way around: coming to a new place is marvelous justification for naïve observations of what is basically your own culture organized a little differently. But also, perhaps, there is a fascination with possible worlds.

A new culture coming to yours is a kind of distorted mirror, in which you can see all your deformities.

Maude: That’s interesting, I wasn’t going to ask this because it doesn’t really apply to you, but now that you’ve brought up your culture, how do you think being Argentinian has affected your writing? I often find that a lot of otherwise very good writers hide behind the idea of exceptionalism to produce stuff that is in fact rather boringly provincial, writing as though the local literary scene was the only one that existed.

Magnus: Oh! I feel for my poor dear colleagues! But I’m with you. Especially when it comes to the local literary scene. It can get so dull that it becomes kind of funny again. On the other hand, one should never forget the dictum: Paint your own village . . .

But do you think it applies only to Argentina? Or is it that it only becomes obvious when you happen to live in a country nobody cares about? Because you can find the same provincialism almost everywhere, especially in America, only that their provincialism, being a world power (also in literature), becomes universal. In appearance at least, because the truth is rather different, and believing otherwise makes for far greater barbarity than our crude provincialism. . . . We at least know that we’re a tiny province of the world and can make fun of it.

Our problem is also linguistic, as it always should be when one talks about literature. In my case, having lived among Spanish speakers from many different countries in Germany, and being a translator who almost always has to translate into a “neutral” Spanish, gives me perhaps a broader scope when writing. I can be very Argentinian, for example when I write soccer stories, but can also strip my language of localism when the book requires distance. It’s something I try to decide book by book, and even if it is kind of awkward having to think consciously about your language whenever you use it, it also opens up more possibilities than if you’ve simply chosen the dominant variant, or a language you think that everybody uses, like people can do with English.

Maude: Absolutely, provincialism is hardly exclusive to Argentina. I think the difference here is the intentionality. However, once again you’ve moved on to my next question! You’re an accomplished translator from English and German. How has that affected your writing? You once said to me that translators are the best and closest readers a writer can have, or words to that effect, something that had never occurred to me before but I think is very true.

Magnus: Absolutely true! Nobody, not even proofreaders, examine a text as closely as a translator, because they have to make sense of it in another language. If I had the money, I would always hire a translator to translate my book before publishing it, in order to be sure it doesn’t have any mistakes. Translation has deeply affected my writing, I think. I get many ideas from the books I translate, and I also sometimes think from a translator’s perspective when I’m writing (e.g., when I make puns or play with idioms). Oftentimes I think of phrases in German or English first, so what I write is actually a translation in itself. I’ve also written a novel in German and one in English, which I guess I wouldn’t have done if I hadn’t had that close relationship with both languages through my work.

By the way, it was a passion before it was a job: a long time ago I won a couple of prizes and had enough money to do whatever I wanted, so I started translating. Now the prize money is gone and translation has become my trade, but I still enjoy it and am even proud of it. Somehow I feel that literary translation is a kind of social work.

Translation has deeply affected my writing, I think. I get many ideas from the books I translate, and I also sometimes think from a translator’s perspective when I’m writing.

Maude: I’d like to think so. I’ll round this off with a dull but often quite revealing question: What contemporary writers are you reading right now? Anyone you’re particularly excited about?

Magnus: I don’t really read much contemporary literature, but there is one Argentinian author I would like to recommend to English-speaking readers, and that’s Mariana Dimópulos, whose book All My Goodbyes (translated by Alice Whitmore) has recently been published by Transit Books. She has a unique style; her books are extraordinarily well written and compelling.

April 2020