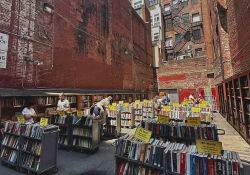

Cafe Ohlone, Berkeley

Nestled in a tiny courtyard shared by the Berkeley Press Bookstore and the adjacent classical music store, Cafe Ohlone is a thriving cultural center for the Ohlone tribe. In spite of both the Spanish and the United States governments’ attempts to assimilate the Ohlone tribe, Cafe Ohlone is displaying their culture in a vibrant and radical fashion through haute cuisine. The indigenous chefs seek to honor the legacy of their ancestors by showcasing their traditional cuisine. Through sharing their food and oral history, the chefs of Cafe Oholne hope to help decolonize their community, dispel stereotypes, and educate the surrounding community about the tribe.

To reach the café, I entered through the Berkeley Press Bookstore, walking through narrow aisles under open-winged books that hung from the ceiling. While attending a tea tasting, I found the café quaint and charming, nestled away from the bustle of the city. In the fading evening light and soft springtime clouds, all patrons sat at one long table with benches on either side. Under crisscrossing fairy lights, the table was carefully arranged with multicolored blankets as tablecloths and decorated with jars of fluffy California lilac. Running down the middle of the table, walnuts, acorns, sprigs of bay leaf, and artemisia are thoughtfully placed alongside shimmering iridescent abalone shells.

With a single table filling the room, I sat with the other café patrons and was integrated into their conversations, as we enjoyed our various teas. We tasted three different teas: stinging nettle, artemisia, and elderflower tea. The tea was served alongside small bites, including hazelnut cakes, chia pudding, and blackberries. As the tea tasting continued, we played traditional Ohlone games with dice made out of walnut shells and abalone. It was refreshing to find myself in a small community space in the bustle of a foreign city, easily conversing with strangers about indigenous communities across the country, language revitalization, and the food itself. While I found the stories of the Ohlone tribe heartbreaking in so many ways, it was heartwarming to hear that their language revitalization was progressing and the tribe was thriving amid the culinary excellence.

Before any food was served, the chefs introduced themselves in their indigenous language, Ohlone Chochenyo, and then again in English. The chefs briefly told the tribe’s story: explaining the hardships of the tribe, the atrocities of the Spanish mission system, the broken treaties of the United States government, and concluding with the loss of their federal recognition. Each course was introduced with a story, told first in Ohlone Chochenyo and then in English. The stories were simple, connecting the freshly foraged ingredients to the local flora and fauna, while the recipes were past oral histories, reminders of family members past. Through combining oral history and culinary excellence, I found that Cafe Ohlone illustrated that in spite of the hardships that the tribe faced, their culture, food, and way of life persevered.