Say “Thank You”

In 1980s Mexico, boys clash off-field during the 1986 FIFA World Cup.

Back then, my father worked installing aluminum parts; frames, mostly for windows, in big buildings.

It was the eighties. And the architects who dreamt of skyscrapers clung to aluminum just like they cling to glass today. Poor taste imposes, as fashions, materials that will later be forgotten.

But sometimes poor taste drags good fortune in tow: one of my father’s customers was a sponsor of the 1986 FIFA World Cup, perhaps the last in which we would witness truly spectacular football.

That’s why one day, on the wooden dining room table, a table I still own today, a pile of tickets appeared.

What I felt when I stood before that stack of papers is hard to explain. My heart sped up, time stood still, and the oxygen in that little room wanted nothing to do with my lungs. It was the first time I was suffocated by an emotion, the first time happiness pushed me to the edge of passing out.

For us, to find ourselves suddenly holding tickets to the stadium, passes to the pitches, was the closest we could get to euphoria.

For us, for whom the World Cup was a privilege even when televised in black and white, with the sound spat out by a speaker that sounded more like an intercom and a signal that depended on the mood of the cats who lived on our roof, to find ourselves suddenly holding tickets to the stadium, passes to the pitches, was the closest we could get to euphoria.

O

EVEN WHEN, A COUPLE of years earlier, celebrating a last-minute goal in a Chivas–América match, my father broke one of my mother’s ribs when he hugged her, picked her up, and carried her around in the air, cheering at the top of his lungs.

Even when, the year before, my older brother had been chosen as a goalkeeper for América’s junior team.

Even when, a couple of months before, my grandmother—a woman reluctant to show her feelings, perhaps even to feel them—had punched the mother of the defender who cost my team a championship in the face, only after insulting her whole family tree.

O

“CAN WE GO to all of them?” I asked when oxygen filled my body again and the chance of fainting was out of the equation. “To all of them?”

“To whichever we want,” my father answered, fanning the air with the tickets in a way I had never seen him move before. At that moment, sanity stepped in: “No, no, no. Only if they let them out of school,” my mother interrupted.

While we were in elementary school, she held out hope that her children would manage to learn as much as necessary. That’s how the times change: the phase of life that everyone believes is essential varies from decade to decade. And in the eighties, that phase was between the ages of six and twelve.

“School schmool!” retorted my father, seizing on a certain bravery I had never seen in him before either: “We’re going to each and every one of them. Here in the DF and in Puebla, in Querétaro and in Toluca.” When we heard that, my brothers and I almost burst with happiness. We shied away, of course, from our mom’s glare, which sought us out like lassos.

“Don’t lie to them,” our mother blurted: “Why do you want to fool them like that?” she lashed out, reaching the corners where we stood with the lasso of her tongue and shattering our euphoria: “Why does football always have to get mixed up with lies around here?”

O

TEN YEARS BEFORE, my grandfather’s heart, a heart that had endured a childhood of hunger and an internecine civil war, that had been ousted in exile and corruptly uprooted, had stopped beating at a match.

Before letting him out, the doctor who saved his life warned him: “No more Barça games.” Then came the first lie: “Don’t you worry, I won’t miss them.”

But, obviously, my mother’s father missed his team from the moment he set foot in the land of good health.

And so, in secret, he started watching the games again. Until, of course, the threat of a heart attack returned and his secret was exposed. Then came the second lie: “Don’t worry, doctor, I can tape them and watch them later, that way I won’t get nervous.” A couple of months later, even though he knew how the match would end up, my grandfather pushed himself to another heart attack.

Even though he knew how the match would end up, my grandfather pushed himself to another heart attack.

After his life was saved, miraculously, came the third lie, this one almost a syllogism: “Atlante wears the same colors as Barça, I can root for Atlante, I won’t get excited.” He kept it up for five years. But in year six, the tachycardia and the sweats returned.

And so the doctor declared: “No more Potros games.” Then came the shared lie: over the course of four years, we made up games among ourselves in which Atlante always won. We even made his team the champions.

My mother still says it killed him to find out: not to know he had been deceived, but to know his potros were never champions.

O

“THEY'RE NOT LIES, I’m not fooling them,” my father answered, not letting go of the tickets in his hand and freeing us all from the lasso that mom had made of her tongue.

“Blanco’s kids are going, there’s no way I’m not taking ours,” he added, hitting mom where it hurt the worst: “Who are his kids gonna play with? What if he gets mad at me?” Blanco, of course, was the aluminum czar, the architect à la mode. And all three of his kids were spoilt rotten.

“We’re going with Blanco’s kids?” I heard myself ask, opposed to the motion, feeling the balloon of my excitement pop and instantly regretting my words: who the hell did I think I was, what the fuck did it matter who we went with when we were going to see our team, when we were going to breathe the same air as Hugo, Tomás, El Sherriff, Negrete, El Vasco, El Abuelo, and Flores?

“What?” my dad asked, turning toward me: “What did you say?” he said, distracted, even more than when my mother had interrupted him: “What the hell did you just say?” His distress was genuine: my immediate bitterness had knocked him off course.

“Calm down, Dad,” my mother cut in: “It’s just kid stuff,” she went on seconds later, surprising my father, my brothers and me. I was already backing off. She continued: “The red, white, and green has plenty of heart to go around.”

O

ON MY BROTHER'S last birthday, after making fun of the fact that our car windows only opened manually and laughing at how the house we lived in wasn’t finished yet, Blanco’s kids burst our ball.

We had them beat in the makeshift street game—my little brother, our neighbor Damián, and I—by ten goals to one (that is, by unappealable humiliation) when the eldest of the three sticky little princes picked up a piece of aluminum can from the ground and sliced our ball open.

It was a miracle we didn’t come to blows. Actually, no, it wasn’t thanks to a miracle that we didn’t end up cracking skulls: it was more due to the fact that that little altar boy, with his soft, priestly flesh, sliced open his own left hand at the same time he sliced open our ball.

And that’s how some phases of life are, especially childhood: even though you hate the enemy, and quite rightly so, you start to get worried when you see him bleeding.

And that’s how some phases of life are, especially childhood: even though you hate the enemy, and quite rightly so, you start to get worried when you see him bleeding.

Actually, no: you start to get worried when they tell you: “If you hit us, my dad’s gonna throw your dad in jail.”

O

“And they’ll show it on the pitch. With their stadium and their fans around them, with guts and glory. Are you sure you don’t care who we go with?” Mom asked me, tightening the lasso of her tongue around my neck and silencing the song in my head.

“I don’t care at all . . . I don’t care the tiniest bit who we go with,” I answered, noticing, along with the fact that I couldn’t breathe again, that my older brother was pinching me: “I meant to say something else,” I added, spurred on by the noose of words and the fingers pressing into my neck: “If we go to all the games, can we root for different teams?”

“Root for different teams?” came the furious response from the chorus my family had suddenly become: “Shut the hell up . . . In this house we root for one team and one team only . . . Mexico is Mexico . . . What’s wrong with this dumbass?” Even though I knew that would be the response, just like I knew why we always rooted for the Águila, I continued to press—or, rather, to provoke—my mom, who had just betrayed me in real time: “Why?”

“For shame, that’s all I’ve got to say, you dumbass, for shame,” burst out my father, turning to face Mom, who backed him up as if they were the same human being. “But why? Blanco’s kids say they’re going for Argentina,” I said then, under my breath, chewing on the rage that had risen into my mouth.

“Those little bastards,” my father exploded: “What do they know about football? What do those dumbasses know about this country?” he went on, fattening up his words until he hit that tone of voice he always used to explain why we go for the Águila.

O

“SEVEN OR EIGHT YEARS ago, after your little brother was born, I went to the stadium to celebrate him coming out healthy. I was happy to see our Potros.

“But my happiness didn’t even last half an hour. The idiot ref lost control of the game, after Basaguren hit Pata Bendita with an illegal tackle. Just like that, the whining turned into pushing and shoving and the quarrel turned into a battlefield.

“In spite of all that, it was a fair fight: one group of men against another. Until a few Potros players came up to some cops and asked to borrow their nightsticks, and then, with clubs in their hands, they let fly on the América players’ heads.

“I couldn’t stand for such injustice. Who the hell would? I let them have it so hard I left my voice in the stadium. Traitors. Cheaters. But I’ll tell you what, the Águila boys put up a fight.

And that’s why we root for them, that’s why we’re for América, that’s why we’re always gonna go for our team, no matter what happens.”

O

“I DON'T WANT YOU all talking to Blanco’s kids,” Dad ordered us when his anger finally got the best of him.

“We’re gonna go to the stadium with them,” he added after a couple of seconds: “But you’re gonna act like they’re not even there.” “You can’t tell them that,” Mom butted in: “How could you even think that?”

“They’re your boss’s kids, and if he wants them to play together, they’re playing together,” Mom insisted, calming down our father and forgetting what she had said just a couple of minutes before: “Our kids will all get along, they’ll be the nicest kids in the world. And grateful, too, because they’re the reason we get to be in the stadium in the first place.”

“Right, kiddos?” she went on, turning toward her children, who, just like at any other time in the history of the world when two bodies are about to crash into each other, only wished to be somewhere else.

“Of course, Mom,” my big brother confirmed, shooting a meaningful nod in our direction: “We’ll be just like you are with his wife.”

Laughter, then, united us as a family once again.

O

CURIOUSLY ENOUGH, the last time we had laughed that way had also been motivated, you might say, by Blanco’s wife.

The lady in question had exited her first marriage, an equation that seemed pretty odd to us in the first place, with two kids, much older than us and much older than the children she had given Blanco.

That Sunday when we laughed, we were waiting at an Argentine steakhouse where we were all meant to eat together and where we would be introduced to these old children. Time passed and the kids didn’t show up, in spite of the hundred times she said: “I think I saw them out there.”

Fed up, Blanco asked to see the menu and then, on his own terms, asking for nobody’s permission, ordered whichever appetizers he fancied. Then, as the waiter withdrew from the table, the lady stood up and ran toward a man whose back was turned to us. Before she reached him she paused, stuck her hand between his legs, and asked: “Whose are these huevitos?”

Surprised, the man, who turned out to be a former footballer and the owner of the restaurant where we would very soon be dining, turned around and staggered backward, exclaiming: “Madam . . . please!” At that very instant, while we were bursting into laughter, the old children of Blanco’s wife walked through the door.

“Oh, oh . . . I’m terribly sorry . . . How embarrassing!” the woman said, taking a couple of steps back herself: “I thought . . . I thought you were one of them,” she added, pointing out her offspring: “I thought you were one of my kids,” she finished, stoking the fire of our laughter.

O

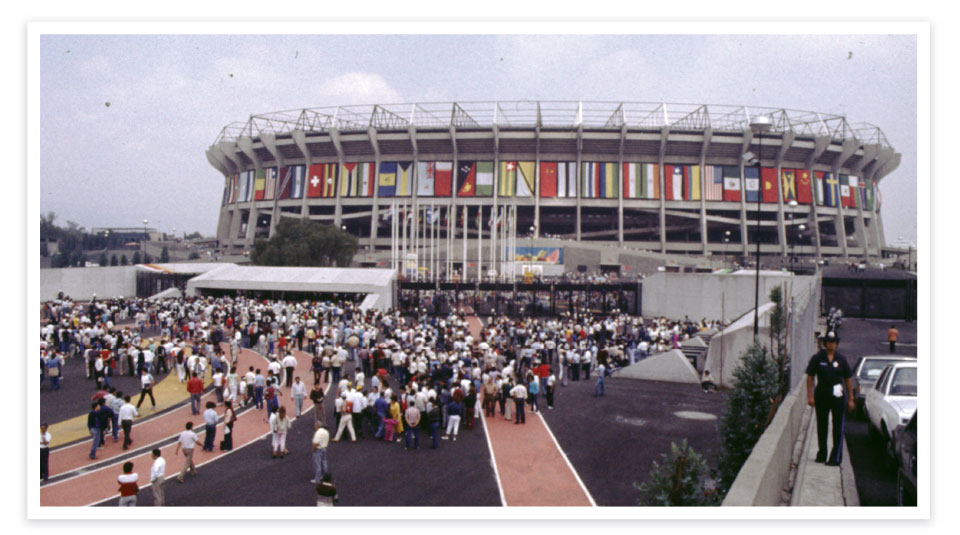

THREE OR FOUR DAYS after the tickets appeared, the moment to go to the stadium arrived. The World Cup was getting underway, and the match would feature Italy, the reigning champion, against a middling Bulgaria.

“I don’t care, even today we’re rooting for Mexico,” our father had said before we set out for the stadium. A stadium at which we arrived three hours early. “We have to meet the Blancos, we have to be ready ahead of time, I don’t want to miss a single thing.”

Outside, at a stand all of whose items were red, white, and green, after begging my mother in vain and almost bawling at my father, I got him to buy me one of those helmets where you stick a soda can on either side, so the liquid flows down little tubes into your mouth, and I transformed into either an astronaut, a robot, or the happiest kid in the world.

My happiness, however, only lasted a couple of minutes. The eldest of the Blanco kids, who had asked to borrow my helmet with a smile on his face, feigned an accident and broke the can holders. The little tubes then became the antennas of an alien.

Neither Blanco nor his wife nor my father nor my mother paid any heed to my tears: they weren’t going to buy me another helmet, not even a T-shirt, much less a flag. Accidents happen.

first substitution

LUCKILY, AS IT GOES in certain phases of life, especially in childhood, my sadness didn’t last forever.

Waiting for her old children to show up, Blanco’s wife left her purse sitting by my side. And out of its open mouth, like paper tongues, poked their tickets to the spectacle.

At the perfect moment—that is, when nobody was watching—I pulled out two of the tickets, angrily folded them up, stuck them in my pocket, and beat a hasty retreat from the scene of the crime. Then, when the old children finally showed up and everyone was all hugs and smiles, I stuck the bits of paper in my mouth.

On the way to the queue, I chewed on my happiness, concealing, of course, the smile on my lips. Then, when we were in line, I swallowed the tickets so as to leave two members of the Blancos stuck outside the stadium.

I didn’t take into account that Blanco was the boss and my dad was the employee. Much less that, after the raised voices and insults between the man and his wife, my dad would offer to stay outside with one of his own kids: “I’ll give you two of ours.”

second substitution

MONTHS LATER, AS THEY did every time a tournament came to an end, Blanco, his employees, and my father had gotten together to fill the last betting pool.

The custom was always the same: Blanco paid the cost of the bet, raised by the number of doubles they put down, and the employees chipped in their part, giving it up directly from their paychecks.

Fate decided that, going into the last two games, the pool between the nine men would be a couple of good calls away from taking first prize.

Tasting glory, Blanco announced: “Since nobody has paid me, I’m keeping this pool to myself.”

extra time

SURPRISED BY MY WORDS: “I’ll stay with you, dad,” or maybe guessing what had happened, my father smiled, stopped walking, took my helmet, and starting putting it back together.

When he was done, he started laughing like he hadn’t laughed in many years. He put the helmet back on my head and, giving it a couple of pats, declared: “Anyway, it wasn’t even Mexico.”

final whistle

ON THE WAY to the stadium, Dad told my brothers and I three or four times that we better say thank you to the Blancos and behave.

Translation from the Spanish

Editorial note: First published in Gatopardo, no. 193 (June 2018).