Metamorphosis in the Old City

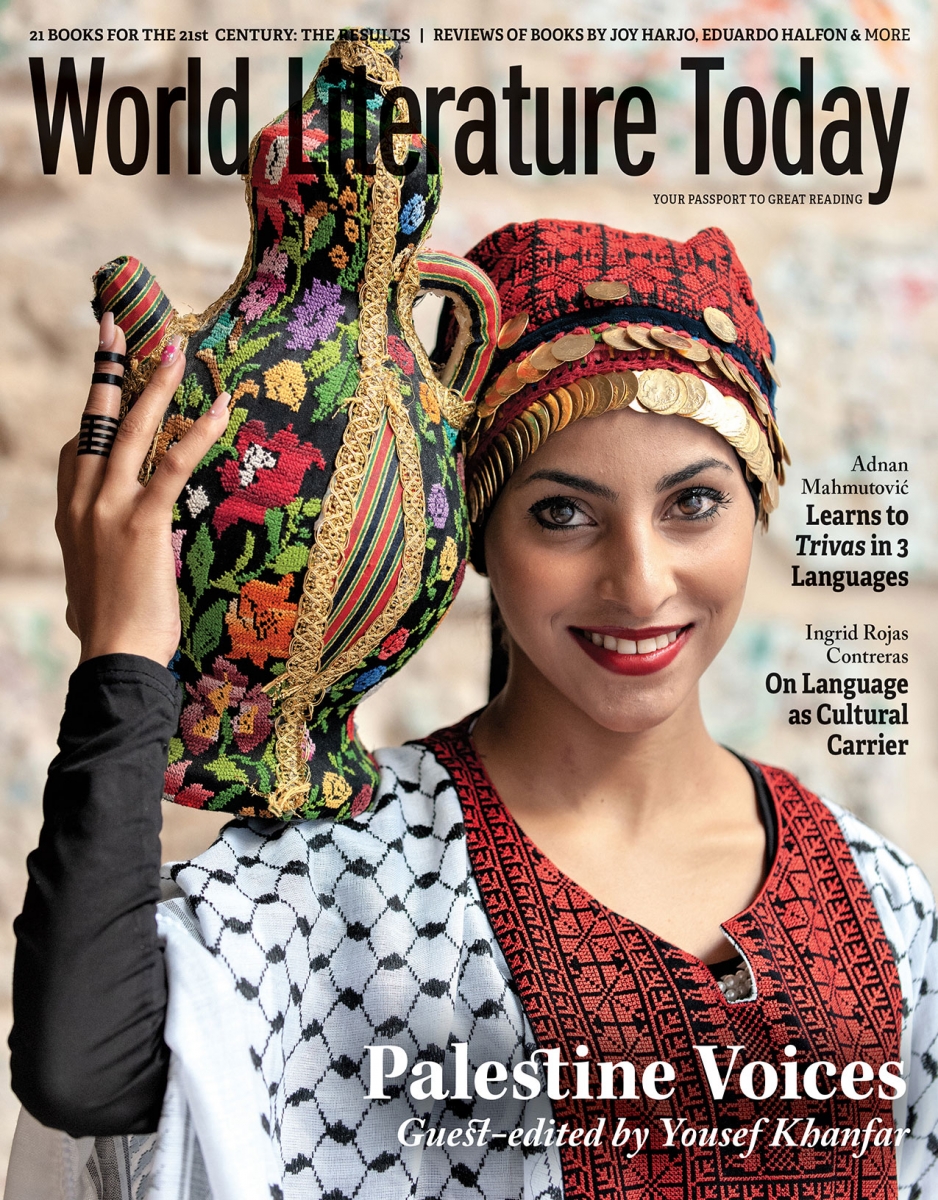

In her debut novel, You Exist Too Much, newly released in paperback, Zaina Arafat’s narrator portrays the fantasies and desires of a young woman caught between cultural, religious, and sexual identities. The following prologue opens the novel.

In Bethlehem when I was twelve, men in airy white gowns sat at a three-legged table outside the Church of the Nativity. They ran prayer beads through their fingers and sipped mint tea in gold- rimmed cups shaped like hourglasses, steam floating off the surface and up into the bright blue sky. I walked past them with my mother and my uncle as we wandered through the holy city.

In Bethlehem when I was twelve, men in airy white gowns sat at a three-legged table outside the Church of the Nativity. They ran prayer beads through their fingers and sipped mint tea in gold- rimmed cups shaped like hourglasses, steam floating off the surface and up into the bright blue sky. I walked past them with my mother and my uncle as we wandered through the holy city.

One of the men called out, “Haram!”

Forbidden. For the especially devout among us, it’s haram to eat meat unless the animal has been killed in a specific way. Haram to drink alcohol. Haram for a pubescent girl to expose her legs in a biblical city. It occurred to me then that I wasn’t a flat-chested kid anymore, that curves had begun to appear along the length of me. I was no longer indistinguishable from a boy child.

Somehow, I had stopped noticing my body long enough for it to change.

“What should we do?” I asked my mother. I felt a pulsing lump take shape in my throat as I noticed her teeth gritting, her jaw extended and temples shimmering. My great-grandparents’ house was where we were staying and where all of my clothes were, thirty-six miles and three checkpoints away. I felt myself go cold as I closed my eyes and prepared to receive her reaction—I knew better than to try and preempt it with an apology. All I could do was strategically try to calm myself, to remember that the anticipation was heavier than the thing itself.

I should’ve had more sense than to dress in such a way when we were visiting the birthplace of a prophet, albeit not our own. My mother had, and still has, a native’s knowledge. She knows the rules instinctively, in that part of the world, and I only ever learn them by accident.

But then, why did she let me leave the house that way? Was this all part of some plan to teach me a lesson? To my uncle, I was ajnabi, a foreigner, which essentially gave me permission to dress however I pleased. But not to my mother. I’d grown used to maneuvering within the lanes of her behaviors, looking to them as guidance, her innate instincts precluding me from finding my own.

“Baseeta,” said my uncle. It’s okay.

My mother looked me up and down. We approached the main door of the church and the men hissed again. My uncle ran the tips of his fingers across his mustache, then looked to my mother and me. “Come,” he said. “I have an idea.”

We followed him into a gift shop just off Manger Square. He dropped a few shekels on the counter, then asked the shopkeeper if we could use his bathroom. My mother grabbed a KitKat off the shelf and tore it open, breaking apart two sticks without a second thought. My uncle dropped three more shekels on the counter. The man pointed toward the back. My uncle thanked him and led the way.

His master plan was that he would trade me his trousers for my Roxy surfer shorts. He went into the bathroom first, and I could hear sounds of fumbling, his belt buckle jangling as it hit the floor. He opened the door slightly and handed his pants to my mother, so she could administer the swap. She then stood in front of me while I took off my shorts. “Yalla,” she said, her most frequently used word. Hurry.

I pulled on the pair of pants. They sagged on me. I had to tighten the belt buckle all the way up to the last hole and then roll the waist so that they wouldn’t fall off, leaving me even more exposed than I had been before.

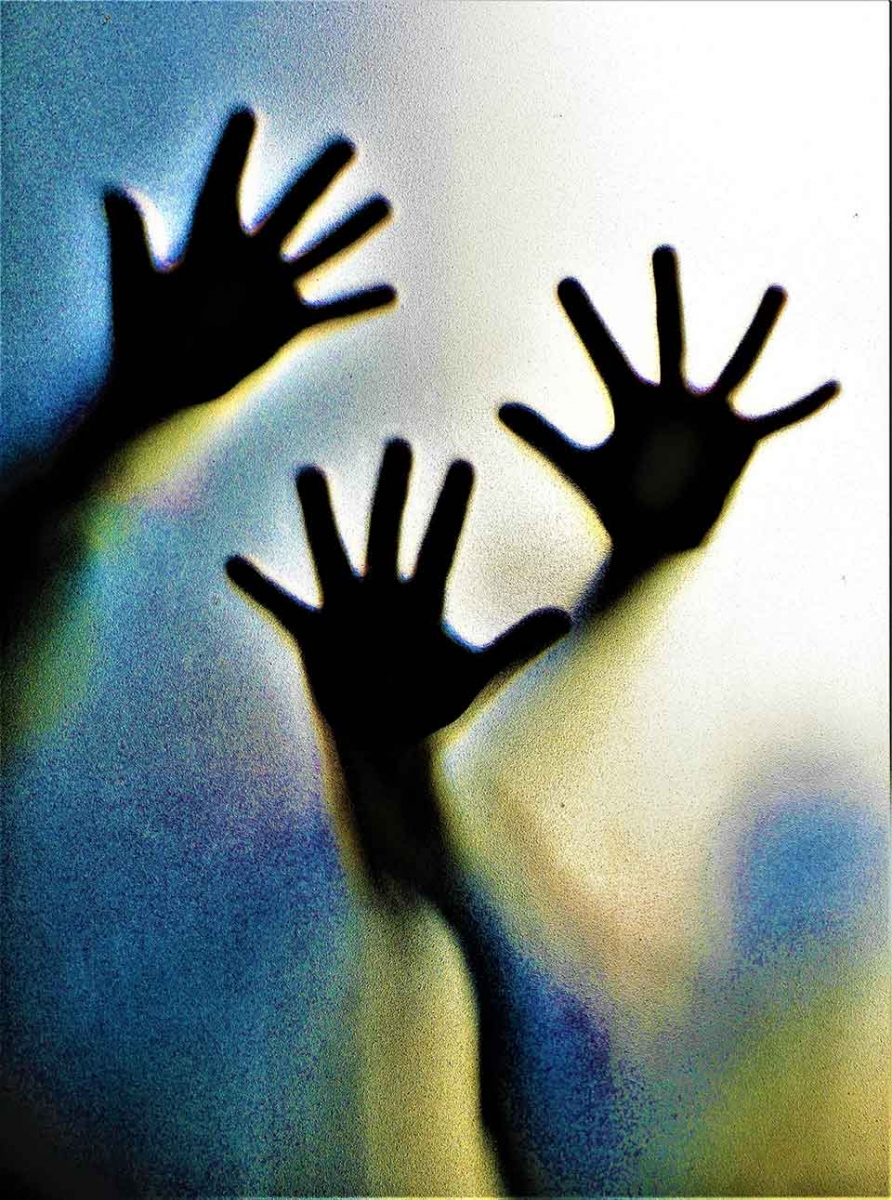

I stepped out of the bathroom and looked at my uncle. I examined my new curves against his ridiculous pasty legs, gangly and covered in sporadic patches of hair, my shorts tight against his thighs like boxer briefs. It occurred to me in that moment to question why, as a man, his bare legs were somehow less troubling than mine. It was a double standard, a shame I had simply accepted until then. In acquiring my gender, I had become offensive.

But as I stood in front of him, an unexpected pride began to swell inside me. I liked the way his trousers made me feel. Seen. Like I could get attention from boys, from girls.

I liked the way his trousers made me feel. Seen. Like I could get attention from boys, from girls.

“Inti walad, willa binit?”—Are you a boy or a girl?

A security guard at the InterContinental hotel in Amman had once asked my cousin Nour this question when deciding whether to lead her into the curtain-shrouded “women’s check” for an intimate pat-down before she could enter the lobby.

“Binit!” Nour had responded. “Girl!” She’d been insulted by the question, the uncertainty it revealed. But not me. Not that day. Wearing my uncle’s baggy trousers, I enjoyed occupying blurred lines. Ambiguity was an unsettling yet exhilarating space.

As we walked back toward the Church of the Nativity I looked at my mother and smiled, desperate for her to smile back. But she withheld. She offered only a freshly disconcerting look, scrunching up her forehead so that lines appeared, her cheekbones protruding, her mouth forming a terrifying expression of indifference. At the time, I couldn’t quite place the source of it. Had she noticed my contentment? Did it scare her?

Only now, years later, do I think I understand. It was in that moment that she first realized: I wasn’t like her. The trousers were a demarcation line, one that separated me from my mother and her lineage.

I wonder sometimes if that day was the start of something. Whether it’s when I began this habit of constant seeking, of endlessly striving to earn my way back, a pattern that would send me on a misguided and self-destructive quest for love. I communicated something to my mother as I stood there smiling in a pair of men’s pants, a message I didn’t know I was sending her. She has always known first what I have yet to discover, has always seen it before I could.

Look at me, I wanted to say to her then. Please don’t look away.

Brooklyn, New York

Editorial note: From You Exist Too Much (Catapult, 2020). Reprinted by permission of the author.