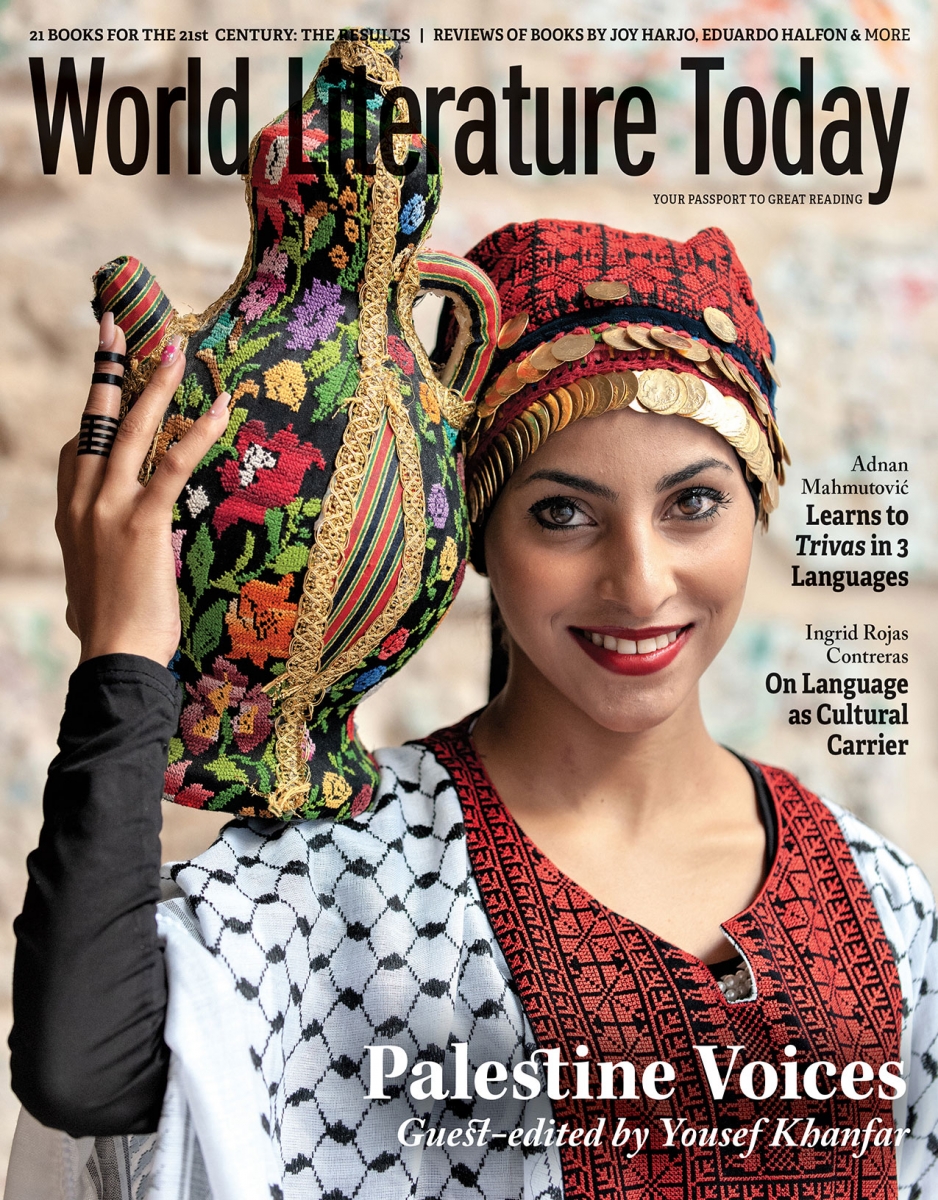

How I Stopped Worrying and Learned to Trivas with Words

A Bosnian Swedish writer considers how extreme nuances and barely perceptible differences, which signify no change in the core meaning of a word, still evoke connotations that widen gaps between us rather than allowing us to trivas with words.

When I was rather new to Sweden, with only a few years of refugee life behind me, I worked in a group of care assistants, and when one of us died, we all went to his funeral. The priest pulled out an electric guitar and played a famous pop song by Ulf Lundell, “Jag trivs bäst i öppna landskap.” I was lost for words, of course, but quite enjoyed it. My first big culture clash. The main verse translates roughly as “I best enjoy being in vast landscapes,” but the Swedish verb trivas really means to thrive, to grow, and in more everyday use to feel good and at home. You can trivas at work or trivas with someone. It signifies that everything is just Swedish lagom, just enough, balanced. It doesn’t ooze the intensity of strong love but evokes a preferred mood or a mode of being. Perhaps it is like that line of Raymond Carver, “In addition to being in love, we like each other and enjoy one another’s company.” I think there is a way to trivas with words and for words to trivas with you like you can trivas with someone you love. It hasn’t always been like that. There is also a way to live with words that make the ground arid. A way to always and utterly distrust words.

The Swedish verb trivas really means to thrive, to grow, and in more everyday use to feel good and at home.

In 2020, the year ruled by the word “pandemic,” Croatian TV ran a segment on a Serbian girl whose family returned to their village, and the news of the day was the fact she . . . drumroll . . . mastered Croatian incredibly fast and won some regional championship. Like she’d learned Mandarin, Arabic, and Sanskrit at the same time. When she demonstrated this mastery for the incredulous audiences, it turned out it was about words like vjeroVatno vs. vjeroJatno (probable). This is very much like the potato/potato thing. For a week I kept expecting this to turn out to be some satirical sketch, a blast from our Monty-Pythonesque past. Nope. Sometimes, or actually, quite often, real-life skits speak volumes. In this case, differences that are, or seem to be, insignificant, are meant to paint some kind of post-Babel world in which neighbors, like those of us from former Yugoslavia, are utterly unintelligible to one another. And this shows that commonality in language does not guarantee a commonality between people(s). I was recently at a big congregational meeting, with some fifty people of the same ethnicity-religion-language, and yet by the end of a very long day, I don’t think more than a handful of words were uttered that brought two people closer to each other.

Surely words can play games with us, such that a single vowel can mean a difference between greeting someone and insulting his mother, but that’s not what I’m speaking about. We can, quite deliberately, use extreme nuances and barely perceptible differences that signify no change in the core meaning to evoke connotations that widen gaps between us.

There are words in my mother-father tongue, Bosnian, that are like that. Words like “easy,” lako/lahko, are anything but eeeeasy. That h has for many come to symbolize the Bošnjak ethnicity while the dropping of the h, the consequence of Ottoman rule in some areas, a signifier of some other nationalist ethos. I love how in Bosnian we insist on hydrating the word coffee with an h, using the Arabic word kaHva (qahwa), which originally meant dehydration and is related to alcohol, to express our Bošnjak pride in our culture and heritage. Kafa and kava won’t do. No, sir.

The crux of the Bosnian, Serbian, and Croatian languages has been this motto we learned at school, by the eighteenth-century philologist and linguist Vuk Karadžić: Write as you speak, speak as you write. Therefore, if you are not some kind of polyglot of your own language, your writing will always betray your level of literacy and your local origin. Sometimes a lost feature, like that graceful h in many languages, is visible in orthographic leftovers to remind us of the road a word has traveled, and sometimes, like in some Balkan languages whose orthography is supposed to reflect speech quite precisely, we have no memory of our lost letters. Either you say and write Historija or you reduce it to Istorija. Once an American researcher on genocide in Bosnia told me she found it hard to distinguish between the hard Č (as in “church”) and the soft version Ć. I told her most Bosnians don’t know the difference, and in many places, it has become a signature of urban space to simply always say Ć, which will cause allergic reactions among my friends from some places where Č is extra hard. Ask any Bosnian to write the name of the famous meat dish ćevap (ćevapčići). I have a friend who tries so hard to do it right that he manages to outsmart himself and does it wrong every time. He would get more correct usage if he only stuck to the soft Ć, whič is obviously the only one he can akčually pronounce.

We also have a hard DŽ (as in John) and soft Đ.

We also have the issue of Capitalization.

We also have that pretty issue of i/e/je/ije as in lipo/lepo/ljepo/lijepo (beautiful), which does not simply designate differences between the three major languages but can indicate class distinctions, so for instance the difference between i and ije in words will make you a peasant or a city-dweller, illiterate or cool literate (never mind some of the latter can’t tell the difference between Ć and Č and are proud of it). I remember my late grandpa chiding me for saying sIkira instead of sJEkira, while now I see a friend insist on saying sikira to mark the pride of his origin. It’s almost like reclaiming certain bad words in the way that many have tried to reclaim racist slurs. Except these words are the same, and struggles over smaller nuances signify bigger struggles of identity, and often it is not just a struggle between ethnicities but within them as well. While both my friend and I would say it’s important to highlight some differences in this process of identification, which is both communal and individual, we do find many of those battlefields utterly ridiculous. These differences won’t let you trivas with words and each other.

In some legends, they say God made humans speak different languages to curb our enthusiasm and prevent us from reaching incredible heights. In other words, linguistic differences made us infinitely split and disunited as a species. In other legends, our linguistic differences are meant to be the incentive to getting to know one another. The unintelligibility of the Other is not supposed to be the reason for derision, for dehumanization, for fear, or nervous laughter. Those are not there so we could tell someone, “Come on, say something so we can laugh. Say anything.” It is supposed to incite translation, a metamorphosis of the self, a desire for connection and intimacy. It is interesting, in the first legend, that unity in a language is supposed to be some kind of superpower, some kind of threat to divinity, and surely that is enough to boost anyone’s delusions of grandeur, but I prefer the second, mainly because I’ve lived it.

Growing up in Bosnia until 1993, I was the kid who studied German for six years, had the best grades, and yet couldn’t speak German to save my life. I had this weird notion that it’s impossible to learn another language, so I didn’t. That was not the only crazy idea I had, but most of them were changed by the war. First, in that limbolike period in various refugee camps, I started forgetting my mother tongue and had one of those Sartrean moments when words stopped meaning. I’d zombie around, if I may use the noun as a verb, if it’s not too freaky. I’d look at things and try to speak their names and they meant nothing. There was no tree in “tree.” “Words, words, words,” Hamlet said when asked what he was reading. I don’t think I even had that.

In the camp, people tried speaking to me in English, and I was so ashamed of myself that I could hardly introduce myself. Then I learned Swedish, probably the easiest language in the world, in a few months and was cured of my stupidity, but also it was the beginning of the end of my existential crisis. Hamlet said to me, “Repeat! Words, words, words.” I found some tapes with English lessons at the library. Fast-forward ten years and I’m publishing my first short story, “Integration under the Midnight Sun,” in English in the US. I’m not sure why I even submitted anything because, although I then knew you could learn another language, I still didn’t believe you could reach any sort of intimacy through it. Who’d read my stories? Who’d understand anything? Hell, I didn’t understand them most of the time.

The editor, a recluse who lived in a cove in the Smoky Mountains, wrote to me: “I’d read this even if it were about nothing.”

Had this been the first and the last connection between people from entirely different cultures, political systems, gender, and all that jazz, it would have sustained my desire to write until death. I was living this legend that promised intimacy through the desire to communicate, intimacy through language. I honored this connection when I published a novel in which the main character lives in that very cove in North Carolina and even tried to learn and use some of that local lingo.

I was living this legend that promised intimacy through the desire to communicate, intimacy through language.

I trivs best in polyglot landscapes, to take the cue from the priest on the electric guitar. I think there is fate in our meeting with words. It’s like finding your Prince(ss) Charming, your soulmate, only there is not just one. ’Tis a polyamorous world, this one. Sometimes there is jealousy, but not much. Sometimes words will hurt you for neglecting them. Sometimes they will ask you for some me-space because you’re suffocating them. What Barthes wrote about lovers applies here, in my warped mind, that the desire in/of words in us is, however particular, discovered by induction and that the words with which I am in love designate for me the specialty of my desire.

There are people I’ve never met except through their treatment of words in those toxic spaces that are social media and whom I know better than my next-door neighbors, whom I love the way the old prophets said God ordered us to love our neighbors. I made friends just by, randomly, fatefully, reading their ramblings about this or that word. I trust with my life people whom I can ask about the provenance of some strange word around midnight and go to sleep only to find out in the morning they’ve been up all night researching the word, checking old dictionaries only their fathers in some land far, far away had under their beds and they had to ask their younger sister to sneak into their parents’ bedrooms and look for meanings unrecorded on worldwide webs.

This same phrase coursed through my body in three languages.

Sometimes we’re moved by words in languages we don’t understand at all, like those refugee years I spent listening to Eros Ramazzotti. Think about millions of people who are moved to tears by the recitations of the Qur’an though they don’t know a word of Classical Arabic. Recently, I found the Arabic translation of Hamlet’s famous words “To be, or not to be, ’tis the question” and said them to my wife as she was crocheting yet another hat. She lit up and repeated those words back at me in Bosnian. This same phrase coursed through my body in three languages. It was a romantic moment of the kind only seen in the greatest and cheesiest romances. It threw me twenty-four years back in time confirming that fateful moment I knew she was the one when she said that weird word “yes.” (Disclaimer: my wife couldn’t care less for Shakespeare. She can’t speak English well and has never read my novels, but sure as hell she can floor me like that.)

I trivs best with words that travel through space and time, like particles, gaining and losing energy, gaining and losing speed. Those words—but this is probably true for all words—are quantum particles that simultaneously exist—literally—in different locations, at different times, and most importantly in different states. You can write entire stories just following a peculiar phrase synchronically and diachronically. Like this prayer called the Bosnian prayer, which another friend-through-words sent me. It is not Bosnian in origin, of course. It started, they say, as poetry in the mind of the great Tagore, probably as fragments, and traveled all the way from Calcutta for a century, over many borders and open landscapes, transformed through different languages, to the pen of a Bosnian translator, and became one of the most cited prayers in all kinds of official and private contexts. The Bosnian prayer jumped into English, and from there it bounced back into the world and impressed people so much they called it by our name. And it is ours. And it is Tagore’s. And it is yours, like all words. At least that’s what the legend says.

And so, in the end, if I may think of, or hope for, the future, my idea of an eternal afterlife is not, as in some people’s opinions, a life in a place where everyone speaks one and the same language, some dialect of the protofather Adam, which encompasses all words that capture the essences of all things; instead, it’s an eternity spent learning millions of languages, getting to know each other, trivas for all eternity.

Stockholm