The Salt Swing

A salt swing, and its story, connects a young woman to her grandmother—and more.

The salt that lay on Grandmother’s lips, and the grief of the story in the glint of her eye, trickled down the lines by her nose, tear by tear, wavering then running straight over her cheek to announce sorrow as joy: “Today is a wedding day, Granddaughter.”

The twist of silk thread she placed on her eyelashes, to weigh down their trembling and make her laughter more beautiful and bring charm and lightness to the angry lines on her face, were like a luminous story from somewhere between the past and the present.

Grandmother sat in the mud, embroidering patterns of domes and camels laden with oil onto sackcloth, to light a lantern of memories.

The mud and Grandmother were connected as if by a pulsing artery: it was a relation of kinship. Whenever the moon rose over the swing in her mind’s eye, its light swept the darkness away from all the distant places and quarters of her spiritual laws.

The mud and Grandmother were connected as if by a pulsing artery: it was a relation of kinship.

Qamar arrived at her grandmother’s house. The house was severed from her grandmother’s childhood by a tall fence of racism and inferiority that was seventy years old, built by a landowner who had seized her grandmother’s land by force and under cover of the law without the heavens consenting to his deeds.

Her grandmother’s house seemed tired from the long years it had stood guard over the skin and bodies of its inhabitants—seven decades now—but it still stood tall even though it was built of mud, which had struggled to hold its own against the passage of time that gnawed at it from every side.

Qamar had a habit, whenever she crossed the threshold of her grandmother’s house, of going up to the hill on the east side, which was covered with flowers and nostalgia, and gave her a glimpse of her grandmother’s memories. She looked out over a tall arch formed of two marble Byzantine columns; people said they were from an ancient Roman or Canaanite temple behind the fence, and others said they belonged to some neglected Islamic monument, while some of the new arrivals said it was a Jewish structure dating from Solomon’s time.

Every time she saw the two columns, she would ask her grandmother about them, lighting the fires of memory in her grandmother’s heart.

Then her grandmother would tell her the story for the hundredth time, forgetting that she’d told it to her ninety-nine times before, and Qamar wouldn’t look bored at all because she knew her grandmother suffered from short-term memory loss and could only remember things from long ago. “Ah now, Qamar,” her grandmother would begin. “Nobody has paid any attention to those two columns for years and years, and on the rare times I lift my face, hunched over as I am, they look hazy because I can’t see clearly these days. I remember playing there as a child. My father hung a swing from them, which we called the salt swing, because salt from the stone rubbed off on its ropes and stuck to our hands as we gripped them, and when we brought our hands to our faces we would smell the burning scent of the salt, and that’s why we called it the salt swing.”

Qamar could feel her grandmother’s intense need to sit on a swing like that. She spent the day at her grandmother’s ancient house, by the fence which severed the past from the sorrowful present, thinking and reading and looking into the distance and watching the butterflies and observing how the place seemed subject to a physics other than that of the city, before her route back to her father’s house in the city, a long way from the countryside and the hills and the fence.

When she entered the house, which was crammed in among the other houses and the shriek of the market and the shrill, sinewy sounds of car horns, she found her father staring at a painting on the wall.

Strangely, the painting showed the very same swing, and the same fence, and the same view, which vexed Qamar, the twitch of surprise on her face turning into amazement and incredulity that for the twenty years she had spent in this house she had not noticed the details of that painting on the wall, or her father’s daily contemplation of it.

How many questions he asked of that painting, how terrible the answers that lay in the details of its watercolors . . .

It was as if the painting had eyes and a mouth and ears to hear and a tongue to explain and a heart to beat, and something deep, deep inside that experienced pain.

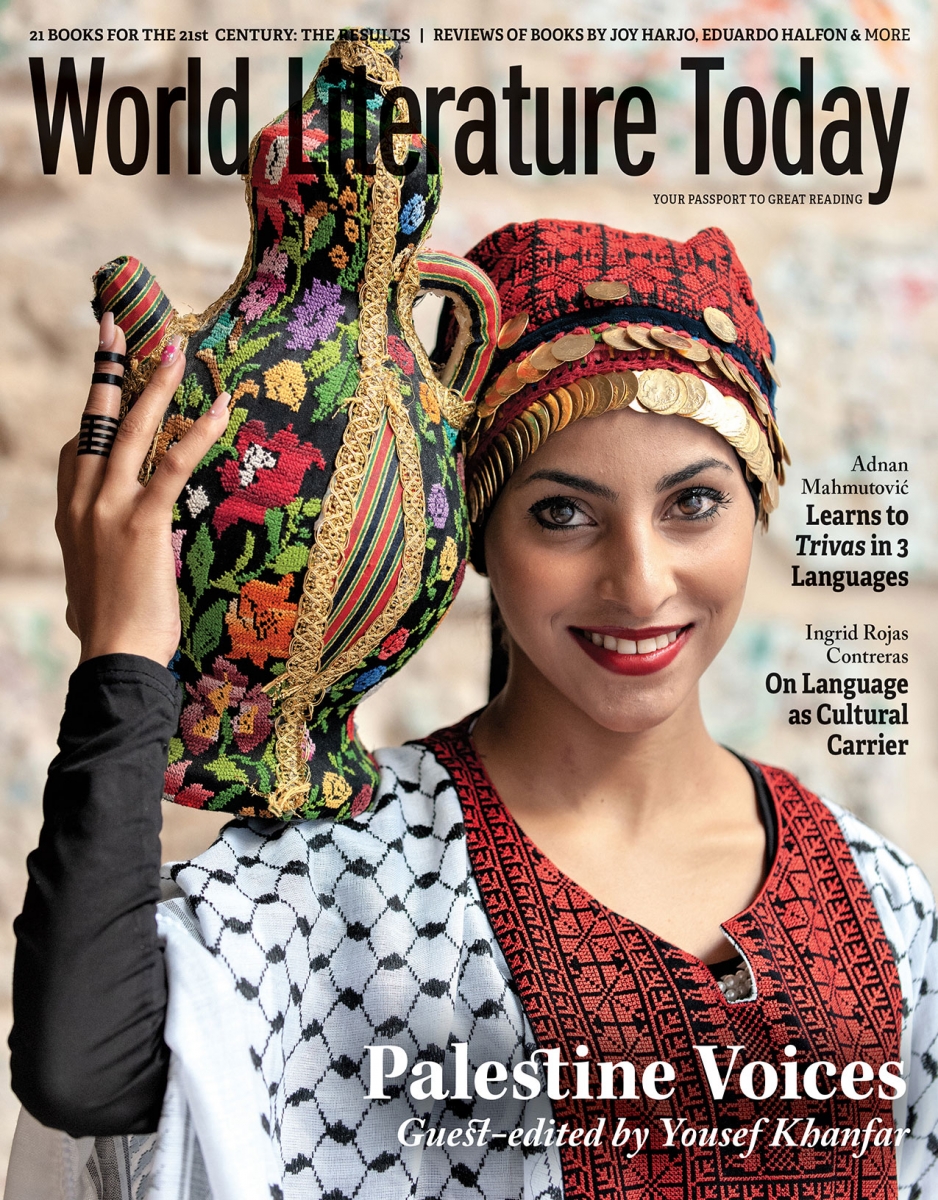

When Qamar’s mother appeared, she made the strange day Qamar was having—a day that had begun with her grandmother’s sad memory of sitting on the swing, and still wasn’t over, because the swing was present in every last corner of every place she went—even stranger. Before Qamar’s eyes, the embroidery on the peasant dress her mother wore resolved itself into marble columns and a swing hanging sadly at the neckline.

In her mother’s hand was a wooden tray with a pane of glass covering a bright patch of peasant embroidery that also showed two columns and the same swing hanging between them.

“Has this being always lived inside us, or was it us who lived inside this strange being without me ever noticing, since my childhood?” whispered Qamar, before asking her mother, “How long have you had that dress?”

“Since you were little!” she replied. “It hasn’t changed.”

“And how long has that painting been on the wall?”

“What’s wrong with you today, dear?”

“Answer me, please!”

“Since you were little, too.”

“What’s wrong with Qamar?” asked her father.

“She’s asking about the painting and the dress.”

“Has she also asked about the tray, and the teapot, and the glass, and the engraving, and the bracelet on your wrist and the necklace around your neck?”

“I don’t think she’s noticed,” replied her mother.

“What’s she doing now?” asked her father. “Where has she gone?”

“She’s in her room, going through her stuff.”

“Maybe now she understands!”

When Qamar went into her room, she sat down and carefully looked through all her things for the swing, the salt swing, that had accosted her since the morning in every corner of the house—three times so far.

Her father wondered if she had noticed the embroidered tray, and the other things, and her mother thought that she hadn’t, but Qamar was extremely observant even in the state of surprise that currently occupied her mind.

The television was showing a program about land and memory, and one of the shots that flickered across the screen was the salt swing. It was significant to the story, and the camera lingered on it more than once.

“No. This has gone too far,” said Qamar to herself.

She got up to leave the room and found her father standing in the doorway smiling. He looked like he wanted to laugh, as if he knew something about the swing but was hiding it from Qamar, until she couldn’t stand it anymore and asked him directly, “What are you hiding from me?”

“I thought you were going through your photos,” he replied.

“Is the swing in my photos too?”

“It is,” said her mother.

Qamar lunged for her photo album and flicked through it wildly, almost tearing its beautiful pages, and there she did indeed find the swing, seated like the queen of all things in among her photos and memories, where it was the backdrop to most of the pictures taken of Qamar as a child at her grandmother’s ancient house.

The thread of memories from other places, too, seeped back to Qamar slowly and distantly, and she recalled kindergarten parties when she was a tiny child barely two feet tall, and school celebrations, and songs on the radio, and politicians’ speeches and those of the mayor, where the swing was the main topic of interest. Qamar felt deeply humiliated: how had the swing passed her by this whole time, without her even noticing that it was the central subject, the issue of all issues?

How had the swing passed her by this whole time, without her even noticing that it was the central subject, the issue of all issues?

“There is only one person who can answer these terrible questions, and that’s my grandmother,” she whispered, just loudly enough for her mother and father to hear.

“I’ll go with you to your grandmother’s,” said her father.

“Come with me, and on the way you can tell me why that swing is so important,” replied Qamar.

Qamar and her father got into his aging car, and he put on a tape of a nationalist song about the swing. Qamar smiled slyly, looking across at her father as if urging him to speak, then added, “Go on, I’m listening.”

We’ve given you the past, the entire past, in a single sentence.

“Your mother and I don’t want years of effort to go to waste; we left you those messages so that you’d find out the story of the swing yourself, maturely and with self-awareness, although it might be painful to learn this way. Now you’re a young woman of twenty, and in a few days you’ll be married and heading to your husband’s house. What you must do is think, alone and only alone, about what that swing means: think about the Palestinian mind, which everybody here shares, ask yourself who that landowner was who stole your grandmother’s land and the swing of her childhood, think about who put Gaza in the situation it’s in today, along with our city and every last one of its corners, think about those who took bereaved mothers and widows to the mountains and camps, to diaspora and destitution and exile, think of the future and the present. Look, we’ve given you the past, the entire past, in a single sentence.”

“I will think of one thing and nothing else.”

“What is that?” said the father.

“I will make you carry my grandmother to the promenade to sit on the swing for a while, because that’s what she needs more than anything. I saw it deep in her heart and in the sorrow in her eyes; I no longer need to know the story of the swing because it pervades every detail of my life.”

Translation from the Arabic