A Stone Necklace from Palestine

A Palestinian-American writer reflects on pieces of Palestinian culture—embroidery, food, dance, a cartoon character—and how they help restore to her a deep and daily sense of home.

Yarn and Yearning

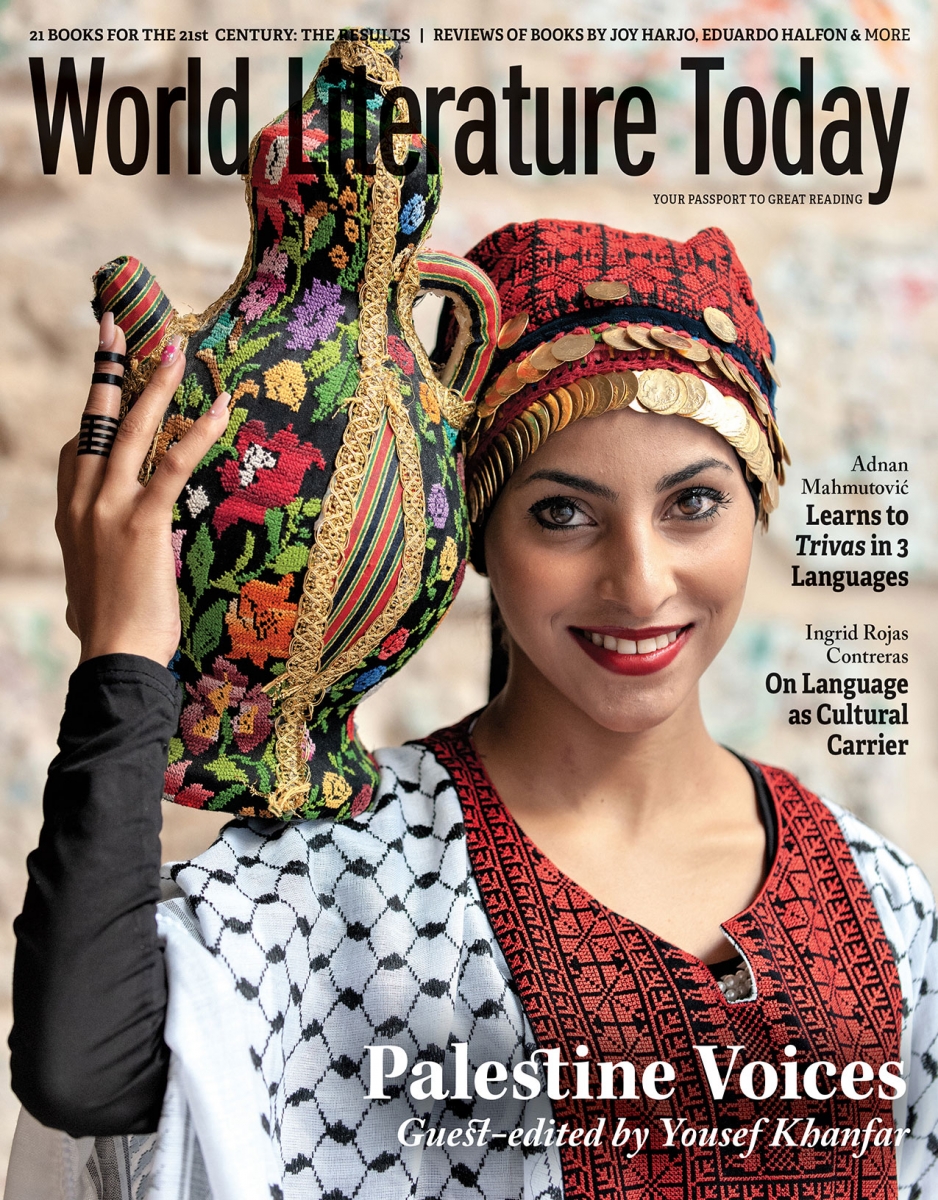

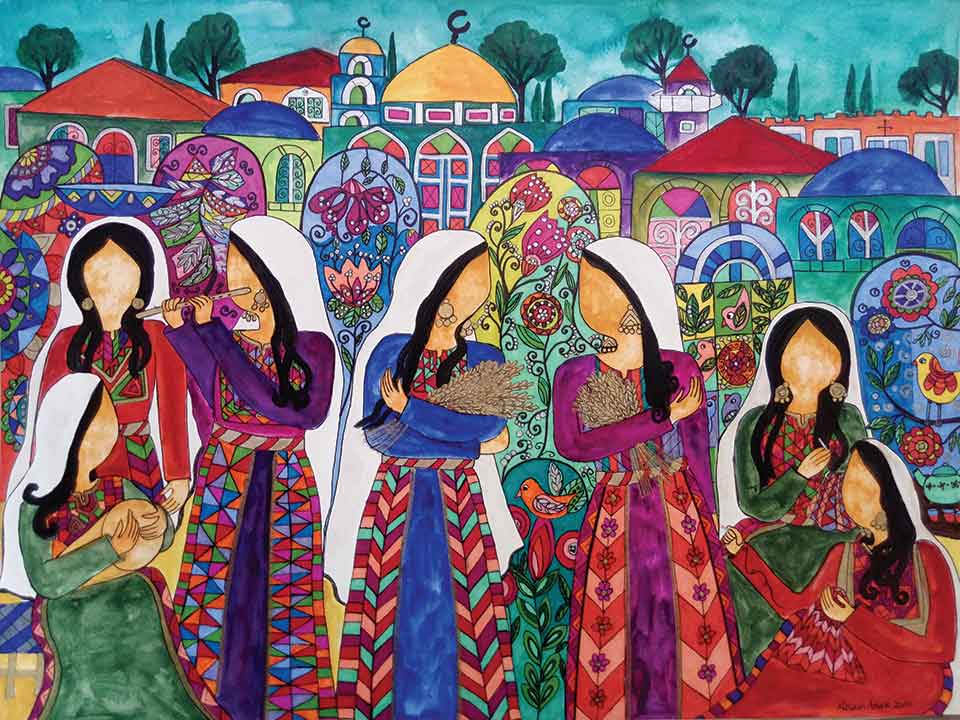

Last year, shortly before Covid-19 occupied humanity’s attention, I went to Palestine with Nobel Prize winner George P. Smith. He wanted to visit Palestine and to see for himself what it means to be Palestinian. On the way home, George chose brocades of embroidery to take home to give as gifts to his friends. Some of the brocades we saw had embroidery of flowers, some had keys, ancient jars, birds, Christian crosses, Muslim half-moons, stars, water wells, people and history.

Palestinian women take pride in embroidering the traditional thobes that have been one of the main hallmarks of Palestinian creative artistry and culture. Each handcrafted thobe takes months, if not years, to embroider. Now the women know to also create embroidered brocades and bookmarks for the tourists to take to freedom with them. The women know that they reknit Palestine into the family of humanity as they send out into the world these miniature pillows where giant dreams sleep.

The small brocades make me think that if they were pebbles, they could be skipped across time and tell the stories of my people in the voices of the women who breathe yearning into yarn as they hold history on their fingertips.

If they were pebbles, they could be skipped across time and tell the stories of my people in the voices of the women who breathe yearning into yarn as they hold history on their fingertips.

I picked tiny stones from Palestine that I planned to turn into a precious-stone necklace. Each stone is precious to me because it represents an element of life that helps me restore to my Palestinian self a deep and daily sense of home. These include tastes, shapes, sounds, fragrances, textures, a whole life in living symbols.

Za’atar and Zait

In the morning, Palestine is on my breakfast table—fragrant, mountain green, mixed with roasted sesame, dipped in golden olive oil, and adorned with sumac that lures the tongue into timeless satisfaction. It’s not olive oil that I bought in a store. I carried it with me across the Atlantic Ocean like an elixir of life. My brother Muhammad and his family had harvested the olives from their field, and I watched the tiny green globes become liquid life at the olive press.

Palestine is synonymous with olive oil. It’s mentioned in the Quran, the holy book of Islam, as a sacred tree. My people have lived by olives for centuries, and tree orchards have often been the main source of livelihood. The minute I see an olive tree, I feel a strong sense of peace. And I remember my father whose favorite way to rest was in the afternoon shade of an olive tree he had planted and watched grow. Guarded by birdsongs of the fields, the butterflies that meander in the breeze and kiss quick hello-and-goodbye, all the fragrant poppy flowers, wild daisies, and elegant cyclamens, he felt most at peace. Thinking of my dad and his love for olives, I wrote the poem “O’Live!” The Boston Children’s Orchestra turned the poem into a song in the repertoire of their international tours.

The minute I see an olive tree, I feel a strong sense of peace.

During my author visit to a Palestinian school, the students came up with a hundred ways the olive is at the root of their lives: They can ride its low branches like a horse. They can eat from it. They can turn its wood into paper. They can create musical instruments from it. They can use the oil for the skin and create soap from it. They can cook with it and know that it does not harm due to its gentle and healthful nature. The students could not stop, as though the olive tree were a family member whom they love.

These memories waft from the breakfast table with warmth as I begin my day. The recipe my grandmother and mother put into the za’atar contains spices that date back to the birth of the concept of nourishment of the heart by the eye before the mouth. You must see the food and love it first. Images nourish too.

I dip my hot bread into this nourishment each morning, and like Popeye eats his spinach, I eat my za’atar and the diaspora is pushed to the margin like Bluto.

Henna and Zaghareed

On days I accomplish a victory in writing or in work or personal life, there is one top Palestinian way to celebrate. I go to the local Arabic shop and buy henna. I turn on music and paint henna tattoos on my hands. Sometimes I choose Arabic calligraphy as a tattoo because of its mythic beauty—namely, that if the twists and turns and ecstatic undulations of love were turned into calligraphy, it would be Arabic.

If the twists and turns and ecstatic undulations of love were turned into calligraphy, it would be Arabic.

The henna lasts for three weeks, long enough for me to see it celebrate again and again. The henna is always best when mixed with the sound of “zagroodah.” This is a cheering sound the women make when something greatly joyous happens.

Now I get a zagroodah on YouTube and play it over and over as I paint with henna. No Palestinian happiness is complete without henna and zaghareed, the plural of zagroodah.

Hummus and Falafel

On Thanksgiving Day in America, I don’t cook turkey. I make Palestinian musakkhan, with flatbread, onions, almonds, chicken, sumac, and olive oil. It’s impossible to leave anything for tomorrow.

On Christmas day I make makloobeh, a Palestinian meal made of layers of rice, vegetables, chicken, and nuts. The name makloobeh means upside down, because flipping the pot and keeping the “rice fort” intact is an art. On the side I make hummus, falafel, and sanboosek appetizers. These are some of the foods my ancestors ate for centuries and perfected in their recipes.

I see hummus everywhere in America now. Few people know that it’s an Arabic word that comes from the Arab kitchen and that they are breaking bread and hummus with Palestinians and Arabs, making the hum (“them” in Arabic) and the us meet and become one, each time hummus is eaten.

Dabkah Dance

My guitar sits in the middle of the living room, holding another world on its strings. That’s because I mainly learn to play Arabic songs on it. Today I learned to play “Ala Dalouna,” the song Palestinians sing when they go to harvest olive trees or wheat crops. The song says: “Let’s help each other.” The winds of the north had changed the color of the crop. Then love songs are added. The wind carries the love, swirling around as many people fall in love in these seasons, and the culture sings on. Playing “Ala Dalouna” makes me feel like I can produce my culture while living in America. I become more Palestinian. I love my fingers in a new way. My heart beats to this song like a Dabkah beat, my people line-dance locking arms together, shaking their shoulders and tapping the earth in rhythms that plough life and plant endless orchards of memories. Dabkah dance makes the earth respond and echo the secrets of its heart in answer.

Hanthalah

An icon of Palestinian spirit of freedom, this cartoon character is as alive in Palestinian culture as the cactus trees he also resembles. His hair spikes out like sun rays and cactus thorns, due to what he sees.

One can only see Hanthalahs in all the cartoons because we are invited to see for ourselves what he sees. He refuses to see for us. His clothes are torn up; however, his voice, his spirit, his freedom are spectacularly renewed and fully alive. Hanthalah was born from the imagination and experience of cartoonist Naji Al-Ali. With Hanthalah, the Palestinian population increased by one timeless citizen.

When I was an undergraduate student at Birzeit University, my classmates wore several charms in their necklaces, including the map of Historic Palestine. Next to it was a gold or silver charm of an olive tree. The name of Allah or a cross joined in. For many of them, Hanthalah in gold, silver, or wood was the fourth.

Palestinian Kufeyyah

Like embroidery, the kufeyyah is a Palestinian symbol around the world. The word kufeyyah itself comes from Iraq where this scarf originated, in a city called Kufa. For decades, however, Kufa the city has gradually moved, if cities can migrate like birds, to the cultural map of Palestine.

When Nobel laureate George P. Smith, who went with me to Palestine, first traveled to receive his award in Norway, he came home with a kufeyyah that Palestinian students in Norway gave to him. People in Ireland, Greece, Australia, America, Japan, Latin America, and many other places perhaps do not know the Palestinian flag, but they know the kufeyyah as the flag of the Palestinian spirit and dream of freedom. Yasser Arafat, the late Palestinian president, made the kufeyyah popular globally because he was hardly seen without it. However, locally, every Palestinian child and every Palestinian group all have the kufeyyah woven into the fabric of Palestinian expression. Palestinian Arab Idol winner Muhammad Assaf is most known for his song about the kufeyyah.

I write these words as my own kufeyyah adorns the wall in front of me. It’s like the world map, with a Palestinian perspective, all countries equal, all distanced properly, all connected creating a harmonious mandala resonant of a nighttime galaxy from white-and-black threads.

Masbahah Beads

My father gave me his masbahah prayer beads. I turned them into Palestine beads. Each one takes me to a memory I love from home. The beads have become a journey for telling a story and going home anytime I choose to:

With this bead, I enter old Jerusalem and walk on the tiny stone steps, counting them like counting the stars. They appear endless.

With this bead I visit Jericho, the Dead Sea and Hisham Palace there, and sit by the gazelles that have survived intact for centuries. I think of the hands that created them, and my heart falls in love with people whom I only see as a mosaic of ancient stone.

With this bead I am visiting Hebron and the arayesh of ripe grapes in the summer hanging like chandeliers in the sun. People sitting under the gazebos playing games or drinking tea with mint or simply soaking in a sense of peace that is found only when one sits with life like one sits with a friend, neither wanting to change the other or be changed by the other—only immense acceptance like grape vines accept fig trees and fig trees accept pomegranates in the same plot of land. They talk with one another endlessly in the language of shade and light.

I think that the Palestinian diaspora not only teaches me how to love across all barriers but how to be a Palestinian feeling at home in the world, anywhere in the world. For home is a stone’s throw near . . .

Columbia, Missouri

Read Joudie Kalla’s recipe for musakkhan.