Alcatraz Is Not an Island

As one of the original Alcatraz activists in 1969, Dr. Dean Chavers credits the occupation for much of the subsequent sea change in federal Indian policy. The following is the unabridged version of his essay.

When we took over Alcatraz Island prison in San Francisco Bay on November 20, 1969, none of us seventy-eight Indian college students involved had any idea of how our actions would impact Indian policy in the United States. But since that time, Indian policy has changed from anti-Indian to pro-Indian, with a dozen and a half laws passed to make life better for Indians.

The world was in turmoil in 1969. The Civil Rights revolution was in full swing. Dr. King had been assassinated. Bobby Kennedy had been assassinated. John Kennedy had been killed six years before, when I was stationed in the Air Force in Waco, Texas. Like most people, I can still remember exactly where I was when I heard the news—outside the electronics building on a break.

It was the height of the Viet Nam War. Lyndon Johnson had decided not to run for president in 1968, leaving the field open to Richard Nixon. The Republican Nixon defeated the “peace” candidate, Sen. George McGovern, in a lopsided election in 1968. McGovern, a bomber pilot in Europe and a war hero, was made to come off as a leftist sympathizer by Nixon and his evil twin, Vice President Spiro Agnew of Maryland. Nixon resigned from office for the Watergate break-in. Agnew took bribes and had to resign.

The Black Panthers were terrorizing Oakland and enthralling the left. Huey Newton and Bobby Seale, the founders, had a highly articulate spokesman in Eldridge Cleaver, who had recently gotten out of prison. All three came to UC Berkeley on a regular basis and made noontime speeches on the steps of Sproul Hall. On other days, anti-war yippie radicals Jerry Rubin and Abby Hoffman made speeches there. Rubin burned his draft card there—apparently for the umpteenth time. Cesar Chavez was leading the United Farm Workers in a struggle to gain adequate wages for Chicano and Filipino workers. Two years later three of us Stanford mass communication students did three media projects for Cesar in Bakersfield. We forced the sale of the anti-farmworker radio station, which would not let Cesar even buy an announcement on it.

The Bureau of Indian Affairs had decided in the early 1950s to end the “Indian problem” by getting Indians off reservations. They shipped Indians from South Dakota and Oklahoma to the Bay Area by the thousands. San Jose, San Francisco, and Oakland had their Indian neighborhoods, the urban reservations or barrios. There was a problem in San Francisco between Indians and Samoans, with fights happening frequently. A Samoan almost killed the Alcatraz leader, Richard Oakes (Mohawk), with a pool cue in 1970 in a bar fight.

There were somewhere between 20,000 and 40,000 Indians living in the Bay Area; the total depended on who was counting, who they counted as an Indian, and how accurate they were. Both Oakland and San Francisco had Indian centers to help Indians accommodate to city living, and San Jose had one shortly afterward. Cleo Waterman, Belva Cottier, Ruby Loureiro, and numerous other elderly Indian women held the Indian community together and were the backbone of all the Indian centers.

Protests against the Viet Nam War and on Third World issues on the San Francisco State University campus and on the UC Berkeley campus in the spring led to the creation of ethnic studies programs on both campuses in the fall of 1969. Other campuses at Davis, Santa Cruz, Sacramento, Santa Barbara, and Chico soon followed. UCLA had started its Hi-Po (“High Potential”) Indian program in the fall of 1969 and brought in thirty to forty new Indian students.

The Alcatraz slogan “Alcatraz Is Not an Island” came to mean that the occupation was about much more than the simple occupation of an island. It was about justice and a better life for Indian people, the poorest people in the United States.

The Alcatraz slogan “Alcatraz Is Not an Island” came to mean that the occupation was about much more than the simple occupation of an island. It was about justice and a better life for Indian people, the poorest people in the United States. It was about Indian self-government and self-determination. It was about Indian pride, preserving Indian heritage, preserving Indian languages, and preserving Indian religions.

The United States had been trying to get rid of Indians for four hundred years. The early settlers spent only a few years in Massachusetts, Virginia, and North Carolina being friendly with Indians. As soon as they had enough strength, they set about trying to kill all the Indians they could find. They almost succeeded; the death rate for Indians in the United States between 1492 and 1867 was about 96 percent.

Then a slight change came about after the Civil War. The churches met in Philadelphia in 1867 and came up with what they called a “Peace Policy.” This was an alternative to extermination. Instead of killing all Indians, they would be defeated by the military, confined to small reservations, and become assimilated into the mainstream. They would have to stop being hunters and become farmers. Indian languages, Indian cultures, Indian governments, and Indian people would all disappear. They would learn English and speak only English.

One leading exponent of this policy was the designer of the Indian boarding schools, Army captain Richard Henry Pratt. He started Carlisle in 1878 with the motto, “Kill the Indian, save the man.” In other words, every element of Indianness would have to disappear. Soon there were over two hundred of these federal Indian schools. Indian students were beaten with leather belts if the matrons and teachers caught them speaking their Native languages. Many of the Alcatraz people were products of the federal Indian boarding schools. I later did my dissertation research at four of these schools.

The schools taught vocational things such as how to milk cows, how to cook, how to do farm work, and how to run washing machines. Later they evolved into schools teaching secretarial skills, auto mechanics, carpentry, welding, and vocational skills. Most Indian schools, and there are now 1,800 of them, still teach these subjects. The federal Indian schools were mostly a failure, with only 10 percent of the students finishing high school. Deaths and runaways were common. Children froze to death in winter on the Northern Plains when they ran away from school and tried to get home.

About 180 of the “Indian” schools are now run or contracted by the federal government. They enroll about 8 percent of Indian students. About 85 percent of Indian students are in public schools. Mission schools and contract schools have the rest. At over 98 percent of these schools, college for their students is not on the horizon. Only a tiny handful of schools, fewer than twenty, are college prep schools, even forty years after Alcatraz. Social change comes very slowly, if it comes at all.

The assimilation policy remained official until a crazy radical came into office. President Roosevelt appointed John Collier as commissioner of Indian Affairs in 1933. He lasted until 1945, twelve years, longer by far than any other commissioner. One of the first things he did was to have Congress pass the Indian Reorganization Act (IRA), which allowed Indians to have some freedom over their lives.

The Republicans were soon mad enough at him to bite nails in half. Some of the western Democrats were not too far behind them. One of the sponsors of the legislation said a few years after it passed that he wanted it repealed and was sorry he had sponsored it. He and others by this time were calling Collier a communist, a fellow traveler, and a pinko. And that was in public. In private they called him much worse names.

As soon as they could get rid of him, they reversed federal Indian policy with a vengeance. They wanted to break all Indian treaties—to “terminate” the treaty rights of all Indians. A couple of years after Collier was booted out of office, the anti-Indians started introducing bills in Congress to terminate treaties. By 1953 it was a reality. Indians were not allowed to testify on the resolution and in fact were not even notified about it. The Congress did not think it had to take Indians into consideration in deciding what was best for them.

Both Republicans and Democrats pushed termination; Truman was in favor of it, and so was Eisenhower. HCR 108, the “termination resolution,” said it was the intention of Congress to terminate all Indian treaties. Over the next decade and a half, a total of 179 tribes had their treaties terminated.

Termination was still hot when the Indian students in the Bay Area took over the abandoned prison on Alcatraz. Indian self-determination, a term that has become the key Indian policy word in the past forty years, had not yet been invented.

Termination was still hot when the Indian students in the Bay Area took over the abandoned prison on Alcatraz. Indian self-determination, a term that has become the key Indian policy word in the past forty years, had not yet been invented. Kennedy was not in favor of termination, but at least one tribe, the Ponca Tribe of Nebraska, was terminated on his watch; he signed the papers. They were the last tribe terminated; their process started in 1962 and ended in 1966.

I was a junior at UC Berkeley in 1969. I ended up as the “mainland coordinator” of the Alcatraz occupation for the first two months. When we got to the dock in Sausalito that night to get on the boats, someone said to Richard, “Who is going to call the media to let them know we are on the island?”

Richard said, “Oh, shit, we forgot that. Dean, you have to go back to the Indian Center and call a press conference for the first thing in the morning. And let them know that we hold the island, and this time it’s for good.” One of the girls from UCLA got cold feet and asked if she could go back with me. We hopped in my car and ran south again across the Golden Gate Bridge. When we got back to the Indian Center it was 3:00 in the morning. We called a press conference for 9:00, and thirty reporters showed up.

The occupation grabbed headlines immediately. It stayed in the news all over the world for months. It lasted from November 19, 1969, until July 11, 1971, a total of nineteen months. Indians from all over the UNITED STATES came to Alcatraz. Some stayed a day, some stayed a week, and some stayed for months.

We set up a bank account the next week. The signatories were the Indian Center director, Earl Livermore (Blackfeet), the board chairman, Don Patterson (Tonkawa), and me. Less than a week after the November 19 occupation we received a check for $500 from an American Airlines pilot from Tokyo, Japan. “It’s time you guys got some of your land back,” he wrote. And the fact that Indians were taking land back—the first time it had happened since 1492—dominated newspaper headlines for months. Shysters and scammers came out of the woodwork, including one of my former classmates from the University of Richmond, offering to raise money for a commission. We turned them all away.

Support came from unlikely sources. Vine Deloria (Dakota), the executive director of the National Congress of American Indians, and Hank Adams (Assiniboine) of the Washington State fish-ins, showed up a few weeks into the occupation with a check for $20,000 from a church group. Rev. Cecil Williams of Glide Memorial Methodist Church had me come address his congregation the second Sunday, and we got a tremendous reception. Glide had black members, catered to homeless people, invited homosexual people to attend, and had rich white members as well. They took up a special collection and gave several thousand dollars to Alcatraz that Sunday.

Harvey Wells (Omaha) showed up a few days into the occupation and tried to become a leader. He stayed on the island off and on for months. Harvey was big, weighing about 250 pounds. On the third Sunday he called me from Los Angeles early in the morning, asking for an update. I told him what was going on, and asked him what it was for.

“I’m going to make a talk at the largest Baptist church in Los Angeles in two hours,” he said. “They have promised to take up a collection and I expect it will be ten thousand dollars.”

We never saw that money. I suspect it went into Harvey’s pocket. How many rip-off artists and fake Indians went around the country pulling the same kind of stunt I will never know. But there were many of them, unfortunately. When Harvey showed up at Pit River a few months later, we ran him off.

Within several days we were receiving several hundred dollars a day in the mail. People in San Francisco started bringing food to the Indian Center, and we would deliver it to the dock for the boats to take it over to the island. I met some of the leading people in San Francisco, including Bea Viguie and her neighbor, George Moscone, who was later the mayor. A crazy city council member, Dan White, a right winger, later killed George, who was one of the greatest lights in the history of San Francisco. George had the ability to become governor and possibly president. He was a great man.

The scam artists included Indians. Sun Bear, whose real name was Vincent Duke (Ojibwa) and had a “tribe” of white hippies near Spokane, came down the first week and was booted off the island. Rolling Thunder, a white man who masqueraded as a Nevada Indian leader for decades, was also asked to leave. Semu Haute, a sometime Chumash Indian and sometime actor, also showed up and was asked to leave.

A host of Hollywood actors showed up, including Anthony Quinn. He had just made a movie called Nobody Loves a Drunken Indian and came to Alcatraz to seek support for it. When the people on the island learned of the title, they threatened to kick his ass right there. The producers quickly changed the name of the movie to Flap, but the movie still bombed at the box office.

Jonathan Winters, the comedian, came for a visit. The singers Kay Starr and Buffy Saint Marie came out and played for people. Buffy also came up to serenade us at Pit River when Sheriff John Balma started throwing us in jail for holding demonstrations at Mount Lassen and at the PG&E campgrounds, trying to reclaim land.

Jane Fonda came, made friends with LaNada Boyer (Shoshone-Bannock), and took her on a round of TV shows and meetings with celebrities. LaNada was one of the original organizers of the occupation. Jane Fonda’s attention caused some of the people to accuse LaNada of getting a big head, which was not true. Nothing could give her a big head. She is the most down-to-earth person in the world and a true Indian warrior. There were lots of guys out on the island who could take lessons from her.

Eldy Bratt, who was an unknown then, spent time on Alcatraz. She is the mother of the famous actor Benjamin Bratt and is an Indian from Peru, South America. I loved her bubbly spirit and constant presence. She had four kids and brought them all out to the island frequently. They stayed out there for months.

George Brown, the Congressman, came and offered his support, one of the few politicians who was sincere and stayed with the cause. Jay Silverheels (Mohawk), who played Tonto in the movies, came and was kind of welcomed. Ethel Kennedy came and people loved her. Grace Thorpe (Sac and Fox), the daughter of the great athlete Jim Thorpe, sold her furniture in Phoenix and came to Alcatraz and stayed. She basically took over public relations from me when I left in early January and stayed with it for the duration. She had been doing very well in real estate in Phoenix, but Alcatraz changed her life.

Willie Brown, a member of the California legislature who was later mayor of San Francisco, was friendly to the Alcatraz occupation. The mayor in 1969, Joseph Alioto, had little use for us. Neither did city council member Dianne Feinstein, who was later mayor after George Moscone was killed, and is now a Senator from California. She is still opposing pro-Indian legislation.

We also had our own navy for four nights. It operated mostly at night, partly illegally and partly legally. Within two days we had twenty-eight boats lined up to carry food to the island. After midnight, two of the boats from Sausalito would run over to Alcatraz with their lights on. They would go around the island from the north and south, headed toward the dock on the southeast. The Coast Guard would chase them, and they would turn and head east. The Coast Guard would take off chasing them, leaving no one to guard the dock. The Coast Guard never got close enough to get their numbers. While they were playing games on the east side of the island, another boat with his lights off would run up to the west side of the island and unload food and supplies. The Indian men would lower a huge net down from the top, and then pull it back up the seventy-degree cliff with food in it. This went on Thursday night, Friday night, Saturday night, and Sunday night.

Then the Government Services Administration (GSA) called off the blockade on Sunday afternoon, and boats could run from the docks at Fisherman’s Wharf to the island. GSA was the legal “owner” of the island after the Justice Department closed it as a prison in 1964. Jo Allyn Archambault (Lakota) and I met with Tom Hannon, the chief administrator for GSA, that first Sunday morning. He had called me to meet with him the day before, and I had called Jo Allyn. “Don’t meet with him by yourself,” she warned me. “You need a witness.” So I picked her up at home at 6:30 that morning and we went into his office at 7:00.

“We are going to take the people off that island,” he told us.

“Mister Hannon,” I told him, “That would be a mistake. There are women, babies, and little children out there. It would look bad if they got hurt.”

To our surprise, he backed off. I suspect he got orders from DC. Late that afternoon we got the word that the Coast Guard blockade had been called off. It was too late to stop the boats from pulling their trick that night, but the next morning the trickery ended and boats went freely to and from the island.

One guy, a Choctaw, had been running his boat out there the whole time. He continued to run after the blockade was called off. After two or three weeks he came to the Indian Center asking us to pay him $100 for every run he had made. He was the only one who asked to be paid. He said Richard Oakes had authorized the payment, which would have been about $5,000—half a year’s salary then. I called Richard, and he denied that he had authorized the payment. We gave him a couple of hundred dollars for his gas and time, and we told him to stop running. We had volunteer boats lined up then, and people with boats kept volunteering for months.

Indians had been on Alcatraz long before. After the Spanish ousted the original Indian inhabitants, it sat empty for over a hundred years. When the United States took control of California after the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848, it took possession of the island, but did nothing with it right away. The island became a military barracks in 1869, and soon housed Indian prisoners. The government sentenced six Modocs to death in 1873 for battling Army troops at Tule Lake, killing a lieutenant and a general in the famous battle of the lava beds. President Grant commuted the sentences of two of them, Barncho and Sloluck, and the Army hung the other four, Captain Jack, Schonchin Jack, Black Jim, and Boston Charley, on Alcatraz.

Hopi, Apache, Paiute, and many other tribes had members who became prisoners on Alcatraz. The government sent nineteen Hopis there in the 1890s because they refused to let their children attend the white man’s schools and be forced to learn English. The federal government kept Indian prisoners on Alcatraz as late as World War II, mainly for refusing to let their young people register for the draft.

The military transferred the island prison to the U.S. Justice Department in 1934, in time for it to become home to the worst criminals in the United States. The bank robber Creepy Karpis, the Mafia leader Al Capone, the bank robber Machine Gun Kelly, and the Birdman of Alcatraz were some of its dangerous prisoners. The swirling currents in San Francisco Bay made the swim to or from the island next to impossible. Supposedly no prisoner ever escaped from Alcatraz. It remained a federal prison until 1963, despite the protests of residents of San Francisco to having a prison in their front door.

There had been an earlier attempt by Indians to take over Alcatraz. In 1964 seven Lakota (Sioux) people, Alan Cottier and his wife, Belva, Martin Firethunder Martinez, Garfield Spotted Elk, Richard McKenzie, and Walter Means and his son Russell occupied the island for four hours one Sunday. They read a proclamation declaring that the island was surplus federal property, and they were claiming it under the 1868 Sioux treaty. Belva, who later founded the Indian Health Center in San Francisco, was the leader and historian of the initial Lakota group of occupiers.

That 1868 treaty stated that surplus federal property could revert to Indian ownership. They offered to pay the government forty-seven cents an acre for the island—the price the federal government was proposing to pay the Indians of California for the 97 million acres of land it had stolen from them in 1850. They got a little publicity, but the press treated it as a joke.

The federal government had sent teams of agents to California to negotiate treaties with the state right after statehood was rushed through in 1850. The agents negotiated eighteen treaties, which they sent to the White House. When the president sent the treaties on to the Senate, however, they were conveniently lost and not found again until 1905. They were locked away in a drawer. Thus California Indians were cheated out of their lands and basically ignored for half a century. Their population dropped from 100,000 in 1850 to only 15,000 in 1900—a death rate of more than 95 percent, considering the births during the period. There had been 300,000 Indians in California before the Spanish invaded it.

For the next half-century, cowboys, ranchers, and miners felt free to kill Indians anywhere they could find them. Their sport on Sunday was killing Indians. Parties of white men would go out looking for Indians and would kill all they could find. None of these killers was ever punished; it was legal to kill Indians in California until after 1900.

Finally Congress started slowly buying small pieces of property for landless California Indians after 1900, calling them “rancherias.” Some were as small as sixteen acres, or forty acres. In the meantime, Indians had been forced to live on the margins of California society, as day laborers, ranch hands, washerwomen, and woodcutters. In some cases they were slaves in all but name. They became the first braceros, or migrant farmworkers, preceding immigrants from Mexico by a hundred years. The California legislature passed a law in 1850 making slavery of Indians legal; it was in force for the next half century.

After World War II the BIA started relocating Indians to the Bay Area. San Francisco and Oakland were one of the dozen areas targeted by BIA in 1950 for Indians to be moved. The others were Chicago, New York, Dallas, Seattle, Phoenix, Los Angeles, Tucson, Denver, Minneapolis, and Albuquerque. “Relocation” was the buzzword of the BIA for Indians from 1950 until 1980. The idea was to get Indians off reservations and then to close the reservations. LaNada Boyer had come to San Francisco on relocation, as had Richard Oakes. Russell Means had gone on relocation four times. Wilma Mankiller (Cherokee) and her whole family had gone on relocation when she was eleven years old.

“Relocation” was the buzzword of the BIA for Indians from 1950 until 1980. The idea was to get Indians off reservations and then to close the reservations.

Relocation worked. A total of 113 reservations and 179 tribes had their treaty rights terminated between 1953 and 1966. Indians had been poor before, but the termination era made many of them destitute. Some tribes such as the Utes in Utah lost half their population due to death and starvation.

The leader of the Alcatraz occupation was a twenty-seven-year-old Mohawk steelworker who had moved to California a few years earlier. Richard Oakes had married Annie Maruffo, a Pomo woman from the Ukiah area, shortly after he got to California. She already had five children and was divorced. She and Richard had another child together in early 1969. Richard adopted Annie’s kids, and they used the name Oakes.

Richard was an Indian nationalist at an early age. Mad Bear Anderson (Tuscarora) told me in 1970 how Richard had hidden away on a bus that was taking Iroquois men to meet with representatives at the United Nations when he was twelve years old. He made the trip with them—almost certainly the youngest ambassador in the history of the world.

Mad Bear and Thomas Banyacya (Hopi) were the unlikely leaders of the White Roots of Peace, an Indian religious group. Bear was garrulous and demanding, while Thomas was a typical Hopi, very quiet and peaceful. But they led people for decades to find their Indian religious roots. I traveled with them for a few years, going all the way to St. Francis, South Dakota, and to the Lummi Reservation north of Seattle. Richard was also a member of the White Roots of Peace. They followed the teachings of Deganawidah, the Huron man who laid out the Great Law of Peace six hundred years ago. The Great Law was the founding of the Iroquois Confederacy, the federation that gave Ben Franklin the ideas of a government of the people that led to the U.S. Constitution.

The most prominent participant in the White Roots was Leon Shenandoah (Onondaga), the Tadadaho or top religious leader of the Iroquois Nations. Leon did not take the lead in meetings. He let Tom Cook (Mohawk), Bear, and other people take the lead. But everyone knew who Leon was, and how important he was.

One time at Rosebud, South Dakota, he approached me with a question. “Who are those people at that Deganawidah-Quetzalcoatl University?” he asked me. I told him Dr. Jack Forbes (Powhatan), Dave Risling (Hoopa), and Tommy Merino (Maidu) were some of the leaders who had taken over an old U.S. communications site and made it into the first all Indian-Chicano university.

“Would you tell them they are not supposed to use his name?” he asked. I said I would. When I got back to California I called Dave and told him what Leon had said. They changed the name to D-Q University instead. Leon had tremendous influence. When he died, the Albuquerque newspaper took a quarter of a page for his obituary.

When I first met Richard in June 1969, I listened to his appeal for about five minutes and had no interest. I went back to talking to the girl sitting next to me and thought no more about it. We were at Carmen Christy’s apartment celebrating our survival of the previous year at Berkeley. Richard had come to the small celebration along with two or three of his fellow students from San Francisco State University.

Only three Indian students were at Berkeley when I got there in the fall of 1968—Lee Brightman (Lakota), LaNada Boyer (Shoshone), and Patty Silvas (Blackfeet). I made the fourth one. I met them all right away. We found out the next year that there was a fifth, Wayne Davis (Chukchansi). Wayne had been paying his way through college slinging hash and did not have much time for socializing. He and I became close friends for the next decade.

There were twenty-eight thousand students on the campus but only five Indians. Two years before there had been none, despite the fact that Indians had been relocated to the Bay Area for two decades by then. None of the colleges had any Indians to speak of. Stanford had two, San Francisco State had none, and Cal State Hayward, where I taught later, had none. San Jose State had none. Mills College had none. UC Davis had none. Sacramento State had none.

LaNada, who was an activist from the time she was a teenager, managed to recruit another dozen Indian students that year. LaNada was married to Ted Means, Russell’s brother, and had two children. She was a twenty-year-old sophomore at UC Berkeley when I got there. She participated in the Third World Strike in the spring of 1969, which led to the creation of a Department of Ethnic Studies that fall. Ronald Reagan had tried to suppress the strike by stationing three hundred highway patrolmen around the campus. It was like a war zone. I was one of the unfortunates who got pepper-gassed that spring. It blinded me for about ten minutes. What a relief when I got my sight back!

Ethnic Studies had four components: Native American Studies, Chicano Studies, Black Studies, and Asian Studies. Lee Brightman (Lakota/Creek), who by then had a master’s degree, naturally gravitated into the position of director of NAS. Steve Talbot, a doctoral student at Berkeley at the time and an Indian sympathizer, also taught part-time.

Richard Oakes had formed a similar program at San Francisco State. He had made friends with the president, the renowned linguist S. I. Hayakawa, who later used his notoriety as an opponent of campus radicalism to win a seat in the U.S. Senate. Dr. Hayakawa had allowed Richard to start a Native American Studies program at SFS that year. Dr. Bernard Hoehner (Lakota), a veterinarian, taught part-time. A white anthropologist and Indian enthusiast named Dr. Luis Kemnitzer taught and helped students put the program together.

I had enrolled at UC Berkeley the previous September as a twenty-seven-year-old junior after spending five and a half years in the Air Force. I had pulled four tours overseas during the Vietnam War, ranging from two months to six months. Despite flying a total of 138 missions that lasted between five and thirteen hours, we still had free time on our days off. I used the time to read heavily.

I had taken advantage of many nights and weekends in Thailand, on Guam, in Georgia, California, Texas, and Mississippi to read hundreds of books. I had always been a heavy reader but became an even heavier reader in the military.

The military time had matured me and made me into a serious and capable student. After a shaky start at the University of Richmond in 1960, where I finished the first two years with a 2.8 GPA, I was determined to do a lot better at Berkeley. I had taken advantage of many nights and weekends in Thailand, on Guam, in Georgia, California, Texas, and Mississippi to read hundreds of books. I had always been a heavy reader but became an even heavier reader in the military. This habit set me in good stead at Berkeley. To get the major I wanted, journalistic studies, I had to make the dean’s list with a GPA of 3.5 or higher. I made it the first quarter and planned my whole course of study for the major immediately after.

Then that December I went back to doing what I had done as an undergraduate at the University of Richmond before I went into the Air Force—working full-time. I got a job as a Burns security guard in December, followed by a job driving a Yellow Cab in Oakland that started in March and lasted until the day after the first student occupation of Alcatraz, which happened on November 9, 1969, a Sunday.

Richard, LaNada, and twelve other San Francisco State and Berkeley students had gotten a fisherman to take them out to the dock at Alcatraz. They landed and spent the night. It made a little news in the Bay area media the next day and then died away. But since they had no food, no sleeping bags, and only the clothes on their backs, the fourteen agreed before noon to leave the island. The Coast Guard loaded them on a boat and took them back to the mainland.

These fourteen people and their colleges, according to LaNada and Mary Lee Johns, were:

- Richard Oakes (Mohawk), SF State

- LaNada Boyer (Shoshone/Bannock), Berkeley

- Joe Bill (Inuit), SF State

- David Leach (Colville/Lakota), Berkeley

- John Whitefox (Sac and Fox), SF Indian Center

- Jim Vaughn (Cherokee), Berkeley

- Linda Aranaydo (Creek), Berkeley

- Ross Harden (Winnebago), SF State

- Burnell Blindman (Lakota), Berkeley

- Kay Many Horses (Lakota), SF Indian Center

- John Vigil (Pueblo), SF Indian Center

- John Martell (Cherokee), Berkeley

- Fred Shelton (Eskimo), SF State

- Ricky Evening (Shoshone/Bannock), SF State

I heard about the occupation when I went to the Native American Studies office at Berkeley the next morning. I had driven my cab until 1:00 that morning and had not heard any news about it. But when I got to the office, everyone was in a frenzy. So all those who could fit into my car crammed in and we headed for the San Francisco Indian Center. When we got there the place was a zoo, with all kinds of people milling around. It stayed that way until midnight. After the frenzy and excitement died down, we started planning a serious occupation of the island.

I insisted that we go back at night, with a large group of people. We should take enough food to last a few days. Women, children, and men would go. We would take sleeping bags, canned milk, bread, and eggs. We would take cooking utensils and prepare to stay on the island. Other students, including LaNada, insisted we go back when the so-called Indian leaders, people they did not trust, would be out of town.

I insisted that we go back at night, with a large group of people. We should take enough food to last a few days. Women, children, and men would go. We would take sleeping bags, canned milk, bread, and eggs.

(These local self-appointed Indian leaders included Adam Nordwall, John Folster, and George Woodward. Adam was the most persistent of these. To this day he claims he was the real leader of the Alcatraz occupation, and even has a ghost-written book out saying that. George ended up being the director of the Bay Area Native American Council [BANAC] for a few months. It was formed to give federal dollars to the Alcatraz occupants to keep us quiet. But George got booted out of BANAC after a year.)

That’s how the date of November 20 got picked. The old heads would be out of town at a national Indian education conference and would not be there to hog the limelight and take credit. Some of them did try to take credit after they got back. Adam never got over the fact that he was not in town when the actual occupation took place. He called a press conference the following Sunday and convinced some of the press that it was all his idea.

Richard had visited a number of other campuses that summer, recruiting students for the Alcatraz occupation. When we went back to the island on November 19, there were seventy-eight students from UC Berkeley, UC Davis, Sac State, UC Santa Cruz, UCLA, and assorted other campuses in the occupation force. The students from UCLA came up in two university cars that they left parked on the street in front of the Indian Center for about two weeks. Finally someone at UCLA missed the cars and came and got them.

The AIM people basically said, “You students have done a good job. We’ll take over and run this now.” Richard’s response was, “Get off this island or I’ll kick your ass.”

Later reports have said that the American Indian Movement occupied Alcatraz; that is just sloppy journalism. Indian college students planned and led the occupation. When five AIM leaders came out to the island after a week and a half, Richard ran them off. The AIM people basically said, “You students have done a good job. We’ll take over and run this now.” Richard’s response was, “Get off this island or I’ll kick your ass.” And he meant it. He was a very tough guy, and the AIM people knew it. They left and never came back.

But the AIM movement took off after Alcatraz. As Russell Means said years later, “Then there was that spark at Alcatraz, and we took off. Man, we took a ride across this country. We put Indians and Indian rights smack dab in the middle of the public consciousness for the first time since the so-called Indian Wars.”

The next year AIM started a series of occupations that would put them on the map forever—Plymouth Rock, BIA headquarters in Washington, and Wounded Knee. The last one was violent, with over five dozen people killed. In contrast, Richard and our attorney, Aubrey Grossman, had trained people in nonviolence before we went over, and we never had a problem or arrests because of confrontations with law enforcement. We did not have any guns, knives, brass knuckles, or other weapons. We were prepared to go to jail peacefully if the police or the federal marshals came to arrest us.

We were prepared to go to jail peacefully if the police or the federal marshals came to arrest us.

Aubrey, who later also became the attorney for the Pit River Tribe, had been a radical before he enrolled in law school. He had the distinction of having attempts to prevent him from passing the bar before he took the bar exam. He had been labeled a communist, a radical, a troublemaker, and a pinko all his adult life. He was a believer in the methods of the Chicago radical organizer Saul Alinsky. The “people power” movement fit right in with the culture of the Bay Area in the 1960s.

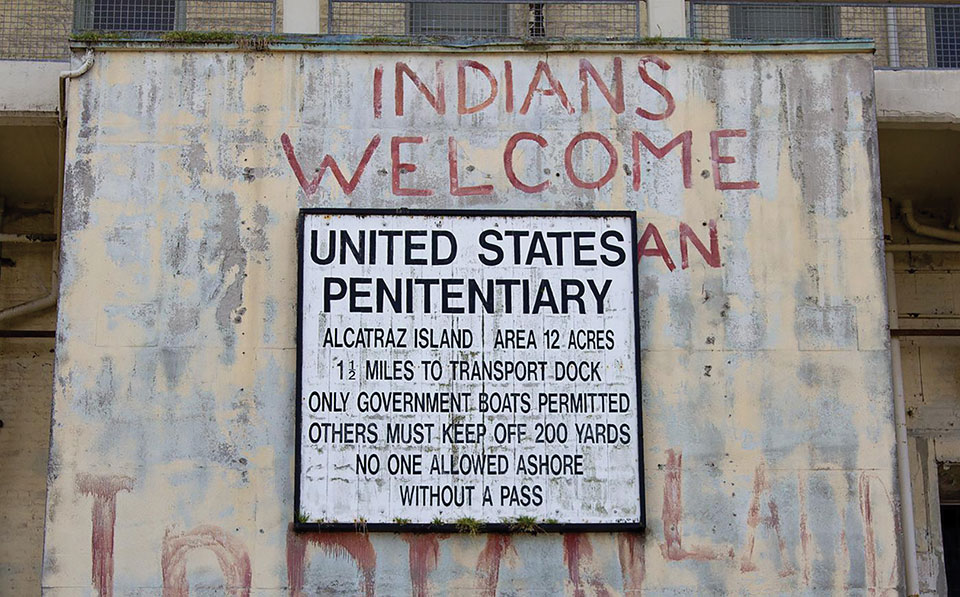

Alcatraz was an Indian nationalist movement from the very beginning. The fact that it was an island struck the inhabitants with the idea behind the occupation. The idea for Alcatraz was to rebuild Indian America. So the logo “Alcatraz Is Not an Island” got painted on one of the walls over the dock within the first few days. Richard, Peter Blue Cloud (Mohawk), LaNada, and others in the student movement had been heavily influenced by the White Roots of Peace, the Indian religious group that traveled the nation for years in the 1960s and 1970s.

Alcatraz was an Indian nationalist movement from the very beginning. The fact that it was an island struck the inhabitants with the idea behind the occupation. The idea for Alcatraz was to rebuild Indian America.

The late Browning Pipestem (Otoe-Missouria) was the Alcatraz lawyer in Washington. He was working pro bono for the prestigious law firm of Fortas and Porter; he later moved back home to Oklahoma and represented many of the Indian tribes in that state over the years. Abe Fortas had been on the Supreme Court until 1969, when he had resigned under pressure. He was very close to President Lyndon Johnson, and his new law firm immediately became one of the top ones in Washington.

Browning had gone to law school with a young attorney who was on the White House staff, and they “back channeled” for months. Nixon would want to know what was going on with the Alcatraz occupation, Browning would call me or Richard, Browning would tell the young lawyer, the young lawyer would brief Nixon every day, and Browning would push for changes in federal Indian policy.

To our surprise, the following summer Nixon announced a highly important change in Indian policy. Acting on his own, this Republican representative of the establishment announced that federal policy would no longer call for terminating (ending) the treaties between the UNITED STATES and Indian tribes. Congress supported his policy declaration a few years later, making it one of the most important changes in federal Indian policy in history (the Indian Self-Determination Act).

As an unpopular politician, Nixon was highly sensitive to criticism. Contrary to popular opinion, Nixon had more social programs passed during his time in office than both Kennedy and Johnson, his Democratic predecessors, put together. And the money to fund these programs dwarfed Kennedy's and Johnson’s spending.

I learned later that Browning had written much of the Nixon Indian policy statement, feeding it to his law school classmate in the White House. Thus this young Otoe lawyer had a hugely important, but almost unknown, impact on federal Indian policy. It was Browning who persuaded the White House that the most pressing issue facing Indian Country was termination of Indian treaties; the huge publicity from the Alcatraz occupation certainly helped.

The Alcatraz occupation led to dozens of Indian occupations of land by Indians, from Chicago to Los Angeles. Indians occupied an abandoned Army base in Davis, California, in 1970 and turned it into D-Q University.

Richard and I spent six months at the Pit River tribe in northern California in 1970, helping them to occupy and reclaim some of their former lands. Mickey Gemmill, the tribal chairman, had been a student at San Francisco State with Richard.

Peter Blue Cloud was the journalist, artist, and poet of the occupation. He published a magazine that some sympathetic printer in San Francisco printed for free. He and Richard had grown up together, and when they were together they always talked in Mohawk. He wrote the most touching poem about Alcatraz:

Alcatraz

As lightning strikes the Golden Gate

And fire dances the city’s streets,

A Navajo child whimpers the tide’s pull

And Sioux and Cheyenne dance lowly the ground.

Tomorrow is breathing my shadow’s heart

And a tribe is an island, and a tribe is an island

And silhouettes are the Katchina dancers

Of my beautiful people.

Heart and heaven and spirit

Written in a drum’s life cycle

And a tribe is an island, forever,

Forever we have been an island.

As we sleep our dreaming in eagles,

A tribe is an island

And a tribe is a people—

In the eternity of Coyote’s Mountain.

Other Indian occupations in the next eight years kept the pressure on Washington to try to improve life on Indian reservations. Among the other occupation were:

- People at Pyramid Lake, Nevada, protested against non-Indians draining their water out before it got to the lake, which is located wholly on the reservation.

- Bernie White Bear (Colville) and other people in Seattle occupied Fort Lawton, which had been Indian land before World War II, and gained ownership of part of it the following year. They turned it into Daybreak Star Center for Indians. Richard Oakes went with them on the initial occupation.

- Protesting the horrible conditions at the Gallup Intertribal Ceremonial, I went with several Alcatraz people and National Indian Youth Council members to protest for a week; we were kicked out of the best bars, stores, and restaurants in town. Indians had to live in what resembled horse stalls.

- Pomo Indians tried to reclaim Rattlesnake Island in Clear Lake, California.

- AIM occupied Plymouth Rock, where the Pilgrims landed, which was its first big media splash.

- AIM occupied the BIA headquarters in Washington, DC, in 1972.

- AIM occupied the little village of Wounded Knee at Pine Ridge in 1972. The Knee had been the site of the slaughter of 150 Lakota men, women, and children in 1890 and was symbolic as being the last armed conflict between Indians and the U.S. Army. The only Indian occupation in the 1970s that was an armed conflict was Wounded Knee.

Indians in Chicago occupied land there. Other occupations happened in Michigan, Minnesota, Wisconsin, California, and South Dakota. But all of them kept the pressure on the federal government, making it possible for pro-Indian laws to be passed for the first time in history.

Nixon returned the 48,000 acres of sacred land around Blue Lake to the Taos Pueblo in 1972. The government had taken it arbitrarily from them seventy-five years earlier. It is their most sacred site. Paul Bernal (Taos) had worked for decades to have this land returned. Nixon also returned the sacred Mount Adams to the Yakama people in Washington State in 1972.

Finally, in 1972, the Trail of Broken Treaties, led by AIM, had people traveling in caravans from the west coast all the way to DC. The brilliant Hank Adams, who had been part of the fish-ins in Washington State, wrote the twenty-point position paper that led much of the legislation over the next thirty years. We are still waiting on some of its most important points, such as the honoring of treaties in Oregon and California that Congress never ratified, to be acted on. Point 14, abolition of the BIA, probably will never happen. The most important point, land consolidation, has never been acted on, except piecemeal.

By 1970 the Congress had passed five thousand laws dealing with Indians. The laws included ones dealing with treaties with a specific Indian tribe, ones establishing the Bureau of Indian Affairs, and one establishing the Indian Health Service. A law had established the Indian Claims Commission in 1946; it let Indians sue the government for lands that had been taken illegally from them; but they could not get any of their lands back. The laws included hundreds of minor ones, such as the law that allowed the president to appoint the chief of the Cherokee Nation. The effects of the laws had been to reduce the role of Indian tribal leaders and enhance the power of federal officials to regulate Indian people and their lives. It was “BIA from cradle to grave.”

Between 1953, when HCR 108, the “termination resolution” had passed Congress, and 1966, the federal government had terminated the treaty rights of some 179 tribes. At the time, this represented about one-third of all the Indian tribes in the United States. The leading proponents of termination, Sen. Arthur Watkins from Utah and Rep. E. Y. Berry from South Dakota, had literally threatened and bribed the two most famous terminated tribes, the Klamath and the Menominee. They were both due large payments of money for timber and lands taken from them; Watkins and Berry told them they would withhold the money if the tribes did not agree to terminate their treaty.

Nixon’s action of reversing termination was a huge step. In the bad 1940s and 1950s, both Democrats and Republicans had one thing in mind for Indians—assimilation into the mainstream culture of the United States. The great liberal Frank Church of Idaho was in favor of assimilation, as was Republican representative E. Y. Berry of South Dakota. Senator Henry “Scoop” Jackson of Washington was an early advocate of termination; he introduced one of the early bills to terminate treaties. (Scoop later reversed his position and introduced the “638” legislation, one of the early pro-Indian pieces of legislation, also called the Indian Self-Determination Act.) Sen. Wayne Aspinall of Colorado, the powerful head of the Indian Committee, was totally in favor of termination. Nixon until 1969 was a proponent of termination.

The leader of the assimilation crowd was Sen. Arthur Vivian Watkins, a Mormon and Republican from Utah. Vivian Watkins did everything in his power to end the treaty rights of Indian tribes, including six small poverty-ridden tribes in his home state. He rode roughshod over Indian rights and could do so because he chaired the Indian Committee almost all twelve years of his two terms in the Senate. The whole Senate acceded to his wishes; there was almost no opposition to his termination resolution. It passed in less than six weeks from the time he introduced it; no Indians were allowed to testify about it unless they were safely on his side. Termination was a surprise to almost all tribes in the United States. Indian input had not been invented yet; both the right-wing conservatives and the liberal “friends of the Indian” knew what was best for Indians.

The ostensible reason for the Alcatraz occupation was to reclaim Indian land and make it into an Indian university. Richard and Dr. Dorothy Miller (Blackfeet) wrote the initial paper calling for this use. But the real outcome was the sea-change in federal Indian policy.

The changes have been astonishing. They have not eliminated the “Indian problem” in most cases. Indian health care is still bad; in some tribes half the older adults suffer from diabetes. Indian County is almost the only place in the United States where tuberculosis is still found. Unemployment on Indian reservations is 45 percent, where it has been for over a century; the federal government purposely created this problem. The dropout rate for Indian high school students is 50 percent, the highest rate in the nation.

* * *

Alcatraz set the stage for the development of positive Indian programs. The news stories about the occupation of Alcatraz, Plymouth Rock, the BIA headquarters in Washington, and the village of Wounded Knee on the Pine Ridge Reservation had long-lasting effects on making it possible to have changes in Indian policy.

Alcatraz set the stage for the development of positive Indian programs.

Some of the Indian people involved in policy change over the next three decades were Pat Locke (Lakota), John Echohawk (Pawnee), Ada Deer (Menominee), Roger Jourdain (Chippewa), Wendell Chino (Mescalero Apache), Russell Means (Lakota), Dennis Banks (Chippewa), Lionel Bordeaux (Lakota), and Bill Byler. For every one of these leading activists there were fifty or more Indian front-line troops who carried the battles to their local congressmen and senators.

Echohawk was the head of the Native American Rights Fund. Deer was chairman of the Menominee Tribe and a professor at the University of Wisconsin. Bordeaux was president of Sinte Gleska College at Rosebud, and the grandfather of the tribal college movement. Byler was head of the Association on American Indian Affairs.

The leading Indian activist and visionary in this period was without doubt Patricia Locke. She was a counselor at UCLA when Alcatraz happened. Most people will work in one movement in their lifetime, and if they are really visionary, they will start a movement. Pat started eight movements, all of which succeeded during her lifetime. She won the MacArthur Foundation “genius award” in the early 1990s for her work; she was one of the first Indians to win it. Her movements were:

- The effort to preserve, protect, and promote the use of Native languages, which led to the passing of the Native American Languages Act. She founded an organization in the early 1970s (the Native American Languages Institute) to address the loss of Native languages; two decades later Sen. Inouye got the historic NALA bill through Congress.

- The establishment of tribal colleges; she personally helped ten of them get started.

- The establishment of a national coalition of tribal leaders, the National Tribal Chairmen’s Association (NTCA).

- The movement to establish tribal departments of education (TDOEs); she saw this bill through Congress and lobbied for its funding.

- The movement to return sacred objects to tribes, which eventuated into NAGPRA.

- The establishment of Native American Studies programs on college campuses. Pat had worked in one of the first ones, at UCLA, and helped spread this movement; there are now over three hundred colleges with an NAS program.

- The movement to establish Native American prep schools, which is still the weakest of her movements. There are only a handful of them, but one of them, the Navajo Preparatory School, is spectacularly successful.

- The movement to establish religious freedom for Indians, which led to the passing of the AIRFA legislation.

Ada Deer’s contributions to changing Indian policy may have been the most important of all these visionaries. She quit her job teaching at the University of Wisconsin and spent the next four years of her life doing everything she could to persuade Congress to reverse the termination of her tribe, the Menominee of Wisconsin.

Their termination had robbed them blind. They did not have control over their own lands and timber holdings, which the legislation from Congress had entrusted to some white bankers and businesspeople in the local border towns. These people acted more like robber barons than they did trustees. After four years of effort, Ada succeeded in getting legislation through Congress that restored the tribe’s federal status. Nixon signed the Menominee Restoration Act in 1972. Ada served the first term as chairman of the tribe, and got their new constitution written, adopted, and approved. Then she went back to university teaching, only leaving the university to serve as President Clinton’s assistant secretary for Indian Affairs from 1993 to 1997.

The Klamath Tribe, the other large tribe that had been terminated, soon regained its federal status as well. The feds had sold the tribe’s large timber holdings off for a song, making the friends of Oregon governor McKay rich people but leaving the Klamath people very impoverished. McKay had served as Eisenhower’s secretary of the interior when termination was just starting. He “volunteered” sixty-two tribes in Oregon for termination, without consulting any of them.

Among the many members of Congress who pushed positive Indian programs in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s were Rep. Sydney Yates, Rep. Dale Kildee, Sen. Henry “Scoop” Jackson, Sen. Daniel K. Inouye, Sen. Teddy Kennedy, and Sen. Ben Nighthorse Campbell. Among the new laws and programs that Congress has passed and the president has signed since 1970, and some accompanying private programs, are:

The Administration for Native Americans (ANA) was the old OEO Indian Desk. In 1974 the Congress passed the Native American Programs Act that authorized a much expanded role for the program. Its prior role had been job training and employment. Its announced role now is promoting self-sufficiency and cultural preservation. In recent years it has added a program to preserve Native languages and another one to deal with environmental concerns.

The American Indian Graduate Center (AIGC) got its start in 1970 when the BIA contracted with American Indian Scholarships (AIS) to operate the postgraduate BIA scholarship program. John Rainer from Taos ran the program for the first couple of decades. Several years ago, the Indian law program at the University of New Mexico that had been operated separately from AIS was combined with the postgraduate program, and AIS won the contract to operate both programs. AIS changed its name to AIGC a decade ago and has awarded more than $44 million in fifteen thousand scholarships to Indian students. It is one of the five largest Indian scholarship programs. It is the Indian partner in the huge Gates Millennium program that funds four ethnic groups—African Americans, Asians, Hispanics, and American Indians. Bill and Melinda Gates gave $1 billion to fund this program—the largest grant in history.

Congress passed the American Indian Religious Freedom Act (AIRFA), P.L. 95-341, in 1978. After outlawing Indian religions for a century and punishing Indians who practiced their religions, the federal government stopped suppressing and prosecuting Indian people for practicing their religion. Among the specific things the government had outlawed were the Sun Dance, the Bear Dance, potlatches, giveaways, the use of peyote in religious ceremonies, the use of sweat lodges, the use of sacred sites, and the use of eagle feathers in Indian religious ceremonies.

Pat Locke was central to the passing of this law, as was the NARF attorney Bunky Echo Hawk. While AIRFA is supposed to protect Indian religions against intrusion, the Supreme Court ruled in the case of Employment Division v. Smith in 1990 that Alfred Smith, an Indian member of the Native American Church, could be denied his benefits to unemployment because he had participated in a ceremony in which peyote was used. The rationale, the court said, was that the state of Oregon, where the case originated, had made peyote an illegal drug. So protection of Indian religions is still not complete.

The BIA created the Bureau of Acknowledgement and Research (BAR) in 1978 in response to requests from tribes for reversal of the termination of their treaties and in response to tribes seeking federal recognition for the first time. Without Congressional authorization, the BIA laid out the criteria for tribal recognition, had it published in the Congressional Record, making the process official if not legal. One way to look at their actions is to view them as an attempt to stop terminated tribes from reversing their termination and to stop tribes that had never been recognized from gaining recognition.

In the next twenty years a total of 191 tribes and groups that claimed to be tribes applied for federal recognition. The BAR has never had federal authorization or approval, but it has assumed the power of life or death over recognizing Indian tribes. It laid out seven criteria that tribes had to meet to be federally recognized, even if they had been terminated.

The BAR has recognized only a dozen petitioners, including the Southern San Juan Paiute Tribe, the Poarch Band of Creek Indians, the Death Valley Timbi-Sha Shoshone Tribe, the Tunica-Biloxi Indian Tribe of Louisiana, the Jena Band of Choctaws of Louisiana, the Wampanoag Tribal Council of Massachusetts, the Grand Traverse Band of Ottawas and Chippewas of Michigan, the Huron Potawatomi Band of Michigan, the Match-e-be-nash-she-wish Band of Potawatomi Indians, the Narragansett Tribe of Rhode Island, the Jamestown Clallam Tribe, the Catawba Tribe, and the Snoqualmie Tribe.

Congress has passed legislation recognizing another ten tribes, including tribes that had been terminated and tribes that had been seeking federal recognition in some cases for decades. Among these are the Cow Creek Tribe of Umpqua Indians, the Aroostook Band of Micmacs, the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi Indians of Michigan, the Mashantucket Pequot Tribal Nation, the Lac Vieux Desert Band of Chippewas, the Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians, the Pascua Yaqui Tribe, the Coos, Lower Umpqua, and Siuslaw Tribes, the Coquille Tribe, and the Little River Band of Ottawa Indians.

The BAR has denied federal recognition to another thirteen tribes, which means the tribe concerned has only one option—recognition by Congress, which is much harder to get than recognition from BAR. In a few other cases, the assistant secretary has recognized tribes without BAR or Congress being involved. They were mostly tribes the BIA had arbitrarily, illegally, and administratively terminated itself.

The court decision in the Tillie Hardwick case reversed the termination of seventeen California tribes. Congress had terminated forty-one California rancherias in 1958. The other twenty-four California tribes that had been terminated are still terminated.

The tally shows that some 150+ tribes have petitioned for federal recognition and their petitions have not been acted upon. And BAR shows no signs of when it will take action.

In several cases in Washington State, the BIA had forced the tribe to sell its land to outsiders or allot its land to individual tribal members, meaning their tribal land was no longer in trust. Then when the tribe petitioned to be recognized again, BIA said they could not be federally recognized because they had no land! And this circular reasoning has held up in court. These tribes are still not recognized; they include the Samish, the Steilacoom, the Snohomish, and the Duwamish (the tribe of the famous Chief Seattle).

At least two tribes have had federal recognition extended to them at the last minute by a Democratic assistant secretary, only to have it reversed quickly by the next assistant secretary, a Republican. This happened at the end of the Clinton administration and the beginning of the George W. Bush administration.

The BAR has declined to recognize a large number of tribes because they did not meet the seven criteria laid out for recognition. But many of the petitioning tribes have simply not had their petition acted on and are still in limbo.

Some of the “tribes” seeking federal recognition have dubious claims to be Indian tribes. In other cases, they are duplicates of existing tribes. Some of the terminated tribes that are seeking to have their status restored are still not recognized forty years after Nixon reversed the termination policy.

In a few cases, the tribes are actually frauds. In at least one case, a non-Indian hijacked the name of a tribe in California and used it to sell memberships to illegal immigrants. He was convicted of a felony and went to prison.

And in still other cases, the petitioning groups have withdrawn their petitions, either because they don’t have a good case or because they are competing with another group claiming to be the same tribe.

There are at least twenty-one states that have tribes recognized by that stat, but not recognized by the federal government. The oldest of these go back to the 1600s in Delaware and Connecticut. It is not likely that any of these tribes will ever gain federal recognition, for complex reasons, and for different reasons in each case.

The Indian Education Act (IEA) was passed by Congress in 1972. Sen. Robert Kennedy had launched a national study of Indian education in 1968. When he was killed, his brother Ted continued the study, which was published in 1969. Teddy immediately introduced a bill to improve Indian education; after three years, the bill was finally passed in 1972. It now provides funding to some 1,100 school districts for supplemental funding for Indian education.

Despite the supplemental help, Indian education is still the worst in the nation, with a 50 percent dropout rate, test scores that are almost always below the twentieth percentile, and the lowest rate of college attendance in the nation (17 percent, compared to 67 percent for the nation). Many of the school districts use the money as they please, not just on Indian students. The major spinoff from IEA has been the National Indian Education Association, whose main function is to hold a large convention once a year. Only a tiny handful of these 1,100 projects—perhaps five—have made improvements in the outcomes for their students.

Several other Indian education associations have been formed since the IEA passed, including the Tribal Education Contractors Association (TECA), the JOM National Conference, and the Tribal Education Directors National Association (TEDNA). A dozen states have formed Indian education associations similar to the first such group, the California Indian Education Association (CIEA), which Dave Risling (Hoopa) founded in 1967.

Catching the Dream started the Exemplary Programs in Indian Education (EPIE) in 1988; it has produced or identified thirty-nine exemplary programs so far. Despite a history of twenty-two years of progress, with some Indian schools going from 70 percent dropouts down to near zero, this movement has affected less than one percent of Indian students.

Congress passed the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA), P.L. 95-608, in 1978 in response to a book by William Byler called The Destruction of American Indian Families. He documented that 25-35 percent of Indian children were taken away from Indian parents by non-Indians. They went to adopted homes, foster homes, and childcare institutions. This process had started with the reservation system right after the Civil War, when the intention of the BIA and the missionaries was to destroy Indian tribes, Indian languages, and Indian cultures. This included destroying Indian families.

Children were taken away from parents because their houses were not clean enough. They were taken away because the mother left a child with her elderly grandmother when she went to work. Social workers took Indian children because they judged that the parents did not exercise enough discipline over their children. They also used poverty, poor housing, lack of modern plumbing, and overcrowding as excuses or reasons to take Indian children away from parents.

Byler testified about his findings in one of the most effective demonstrations of fact in Indian history. Congress almost immediately declared its intention to protect the best interests of Indian children and to promote the stability of Indian families, reversing the policy of assimilation stated in the Dawes Act of 1887. The courts and the social service agencies are still fighting many battles over this law. The National Indian Child Welfare Association (NICWA) was formed to try to enforce this law; it is made up mainly of Indian social workers.

Congress passed the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act (IGRA), P.L. 100-497, in 1988 at the request of Nevada and New Jersey gaming interests. They did not want the competition from Indian tribes that was emerging in southern California, New York, Florida, and Connecticut. It established the federal National Indian Gaming Commission (NIGC) with three people as commissioners to regulate and monitor Indian gaming in the 300+ tribal casinos that are now operating. The tribal members soon formed their own association, the National Indian Gaming Association (NIGA), which has become perhaps the best Indian lobbying operation in the nation. Gaye Kingman Wapato started NIGA on her kitchen table right after her term as executive director of the National Congress of American Indians was completed in 1991. Rick Hill (Oneida) and Ernie Stevens Jr. (Oneida) have provided its leadership for a decade and a half.

Indian gaming has been a windfall for the small tribes with large casinos near large urban areas. These include Connecticut, Boston, Miami, Tucson, San Francisco, San Diego, Los Angeles, Albuquerque, Tulsa, Oklahoma City, and Minneapolis. But the small tribes that own these casinos have only about 5 percent of the total Indian population; the other 95 percent of Indians get no benefits from these casinos. The Foxwoods Casino in Connecticut, owned by the Mashantucket Pequot Tribal Nation, is the largest casino in the world. The Mohegan Sun just down the road is also one of the largest.

Some of the tribes with large casinos are developing businesses and casinos with other tribes, so the wealth is slowly reaching the rest of Indian Country.

Congress passed the Indian Health Care Improvement Act, P.L. 94-437, in 1976 to improve the health care system under the Indian Health Service. It includes a program of scholarships to Indians to study medicine, dentistry, psychiatry, nursing, and pharmacy. This program has funded over eight thousand Indian students in the critical health care fields. P.L. 94-437 aimed at improving Indian health and involving Indian people in the process. The Indian Health Service saw its budget more than doubled under Nixon between 1970 and 1975. The problem was that its budget had been below anemic. The budget for FY 1970 was less than $107 million. The budget for FY1972 was $235 million. Indian health organizations established the National Indian Health Board in 1972.

But the huge increase still left Indian Health way below the needed numbers of doctors, nurses, psychiatrists, pharmacists, and veterinarians per thousand people in the United States. The service, which operates or contracts for 180 Indian hospitals and clinics, still has a 35 percent vacancy rate for its professional positions. The life expectancy of Indians has improved in the past fifty years from about forty-five to over sixty-five, but it is still below the national life expectancy rate of seventy-five.

Indians were literally dying while they waited to be seen by a doctor at overcrowded Indian hospitals and clinics. God help urban Indians, because the hospitals wouldn’t. If you were from South Dakota and got sick in Albuquerque, the hospital people would tell you to go home to South Dakota to be treated. That’s a two-day drive. From San Francisco to South Dakota is a three-day drive.

Few Indians could afford to drive that far for an infected tooth or an eye infection. So they suffered. Belva Cottier, the first lady of Alcatraz, led the fight during the 1970s to establish urban Indian health clinics, with San Francisco being one of the first. The leaders of the urban Indian health movement first had to get a bill through Congress to fund the program, which was new. But the legislation did not pass until 1992, almost twenty-three years after Alcatraz. The feds now report that 150,000 Indians use the thirty-four urban Indian health clinics and that their health had deteriorated before they had health care available.

The Indian Self-Determination and Education Act of 1975 (P.L. 93-638) began the process of bringing self-governance back to Indian Country. Sen. Henry “Scoop” Jackson of Washington sponsored this legislation. Prior to 638, tribes had little power and authority. Scoop had sponsored one of the first termination bills but by 1972 had reversed himself and became an advocate for self-determination. He needed Indian help when he ran for president in 1976.

Before 638, it was the BIA that determined where Indian children went to school, what leases on Indian land, timber, water, and minerals were contracted, the payments to individual Indians of welfare and other monies, and other important matters. The BIA ran things on the reservations, and the tribes just watched. After 638, tribes could contract to operate these services themselves. Everything from tribal government to tribal courts, jails, tribal enrollment, education, social services, and other functions could be included in a 638 contract. Ten years later, the Indian Health Service functions were also included in the contracting provisions of the 638 legislation.

Sen. Daniel I. Inouye (HI) sponsored the legislation to found the National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI) in 1989. The museum is located in Washington, DC and is part of the Smithsonian. It has a special mission to preserve traditional Indian arts, relics, cultural objects, religious objects, and other artifacts. Many of them have been stolen from tribes and Indian individuals over the past four centuries.

The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) was a law passed in 1990. It required the return of sacred objects to Indian tribes, mainly from museums that had acquired them in the 1800s. These include human remains, funerary objects, sacred objects, and objects of cultural patrimony. Hundreds of thousands of Indian cultural objects had been carried away from reservations by curiosity seekers, museum curators, traders, university professors, and others. In some cases, these objects were obtained legally; in others they were obtained illegally or in a shady deal.

Some of the objects were crucial to the religious observances of the tribes. In other cases they were human bones or parts of bodies, including Ishi’s brain. (Theodora Kroeber, the wife of famous UC Berkeley anthropologist Alfred Kroeber, wrote a book about Ishi that was published forty years ago and is still a bestseller. The Smithsonian had preserved his brain for almost a century before it was returned for proper burial. The late Mickey Gemmill and some other Pit River people finally repatriated his brain and buried it in a secret location a few years ago.)

Over 32,000 human remains have been returned to Indian tribes for proper burial. Hundreds of thousands of other objects have been returned to Indian tribes from federal agencies and museums that receive federal funding. This misappropriation has been a major item of contention with Indians for a long time.

The Native American Journalists Association (NAJA) had no connection to any formal federal legislation and was started twice. The organization launched in the early 1970s, with the late Richard La Course and Chuck Trimble. It lasted a decade before it ran out of funds. Richard functioned as a bureau chief at UPI or AP, collecting news stories and sending them out in the mail to the Indian newspaper subscribers. At one point there were close to two hundred Indian newspapers; that total now is just over one hundred. The Reagan recession of 1982 and the Bush recession of 1992 both saw Indian newspapers close their doors, many of them never to open again.

Tim Giago got funding ten years later from the Gannett newspaper chain to start the organization again, and it is still functioning. It now has newspapers, magazines, radio stations, and TV stations as members.

The major shortcoming of Indian newspapers is that most of them are owned by tribes, which use them mostly as propaganda sheets for the tribe. They often do not cover hard news, even news that affects the tribe.

The Native American Languages Act (NALA), P. L. 101-477, passed Congress in 1990, but with no funding. Pat Locke succeeded in getting this bill introduced. It was highly important in itself, because it reversed 120 years of a federal policy. President Grant accepted the recommendations of a group of missionaries in 1869; they called for the confinement of Indians to reservations, forcing them to send their children to school and learn English, stop hunting and learn to farm like white people, and eventually lose their Indian identity. Alcatraz made it clear to many people in the United States that Indians had no desire to lose their languages and their Indian identity.

The following year Congress approved funding for the act, and it has been in operation ever since. It was funded just in time; publications from Northern Arizona University in the 1990s reported that of the three hundred extant Indian languages, most were in danger of being lost within a few decades. Large numbers of the languages were already extinct; another large group was only spoken by two or three elders, and when they died the language would die with them.

The Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission (NWIFC) is the brainchild of the late Billy Frank (Nisqually) and his son Billy Frank Jr. One of the first phone calls into the San Francisco Indian Center the night of November 20, 1969, was from Billy Frank Sr. He was all excited when I talked to him on the phone. In a deep bass voice he said, “It’s about time we took some land back. We are going to send some people down there.” The next day Al and Maiselle Bridges (Mr. Frank’s daughter), their son-in-law Sid Mills, and his wife, Allison (Al and Maiselle’s daughter), showed up to support the occupation.

The Franks and the Bridges family had been involved in trying to protect their right to fish in their usual and accustomed places for two decades by then. Al Bridges, Billy Frank Jr., Sid Mills, and others were arrested dozens of times by state and county game wardens and law enforcement officials. Billy Jr. was arrested fifty times. Hank Adams, a young Assiniboine intellectual who was also a fish-in activist, had been shot in the stomach by one of the local rednecks who were trying to keep Indians from fishing and almost died.

The treaties the Indians of Washington State signed with the federal government in the 1850s promised them that if they agreed to relocate to reservations they could still fish and hunt as they always had. This meant they could fish at places that were not part of reservations if they had fished there before the treaty. They had fished for salmon and steelhead trout in the rivers for centuries; fish were a major part of their lives. But the state and local game wardens had started decades earlier enforcing state law, which regulated fishing and hunting on all lands in the state that were not federal Indian reservations. They arrested Indians who fished at places off their reservations.

Finally, a court decision in 1974 (the Boldt decision) ruled that the Indians of Washington were entitled to half the fish in the rivers, which is still upsetting sports fishermen in the state. They elected their main champion, Slade Gorton, to a term in the U.S. Senate before Indian opposition knocked him out.

Overfishing by sport and commercial fishing had reduced the salmon and steelhead runs by over 75 percent by the time of the Boldt decision. The NWIFC established pursuant to the Boldt decision has slowly built the salmon runs back up. Billy Frank Jr. is the longtime chairman of the commission. Indians are teaching the Northwest how to conserve one of their most precious resources.

Nixon established the Office of Indian Water Rights in 1972 to protect the most precious Indian resource in the dry West. People in the East have no idea how important water is in the West. The East gets forty to sixty inches of rain a year; the West is lucky to get 10 inches. So to live in the west, people have to rely on rivers, ponds, ditches, aquifers, snow in the mountains, and a few deep wells. Water is more precious than gold to westerners. The Winters doctrine of 1908 had reserved the right of an Indian reservation to have enough water for its uses.

Indians have taken many a beating in the battle over water on reservations. Farmers, miners, ranchers, loggers, resort operators, and developers had done all they could to extract every drop of water they could for their operations. An Anglo man and federal lawyer named William H. (Bill) Veeder for years did yeoman’s work in protecting Indian water rights. Even though he was a federal employee, he spoke up strongly for Indian water rights. After his retirement from the government, as an attorney he represented many Indian tribes in their water rights battles.

The federal Office of Native American Programs (ONAP) in the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) is the federal agency charged with meeting the housing needs of Indian people on reservations. The National American Indian Housing Council (NAIHC) is the association formed in 1987 to push for better housing on Indian reservations.

The federal government has initiated a number of housing programs since 1970 to meet this need. But Indian housing, most of it built or subsidized by HUD, is still very inadequate. The lack of adequate housing is related, of course, to the huge rate of unemployment on reservations, which is 45 percent.

Congress finally passed the Native American Housing Assistance and Self-Determination Act, P.L. 104-330, in 1996. A major national study found that 30 percent of Indians were living in inadequate housing. A third of Indians were living in overcrowded conditions. Many are still suffering from lack of sanitary facilities, lack of running water, and lack of electricity. Forty percent of Indian housing was overcrowded, compared to only 6 percent for the nation. Over ninety thousand Indians were unhoused or homeless. Many Indian homes had no water or electricity, and phones were still rare on rural reservations. Some 25 percent of Indian homes had no indoor plumbing, a rate that was twenty times the national rate.

There was an immediate need for two hundred thousand units of housing in Indian Country. The assumption that Indians would eventually leave reservations and assimilate into the mainstream was finally found a century later not to be happening. Congress finally realized that Indians were not going to die off or go away.