The World of Alain Mabanckou

Whether dealing with fashion, music, language, colonialism, contemporary immigration policies, gender relations, masculinity, or globalization, Alain Mabanckou’s work can be qualified by a broad spectrum of avant-gardist qualities.

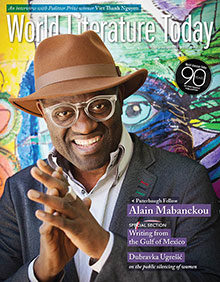

The Congolese have the reputation for being dapper dressers, fashionistas, for always appearing in public dressed impeccably. This art is known as the S.A.P.E., the acronym for the Society of Ambiancers and Persons of Elegance, and Alain Mabanckou is one of its best-known practitioners. Striking images of him are to be found gracing the covers of magazines, but the author who has captivated readers worldwide for the past two decades, as well as thousands of Twitter followers at #mabanckou, is above all known as a master of style who has taken literature in new and exciting directions.

Alain Mabanckou was born in 1966 in the Tié-Tié neighborhood of Pointe-Noire, just a few years after the official end of French colonialism, some nine thousand miles away from Los Angeles on that other West Coast. Named Ponta Negra by Portuguese adventurers in 1485, Pointe-Noire was a city of 20,000 inhabitants in 1950 that had burgeoned to 360,000 in 1994, by which time Mabanckou had completed his legal studies in Paris and was busy working as a legal advisor for the multinational power company Suez Lyonnaise des Eaux. But the economic capital of the Republic of the Congo, home to the famous Congo-Ocean Railway station that links the Atlantic port with the capital Brazzaville, is where one of Mabanckou’s uncles owned the trendy Joli Soir, a legendary nightspot at which the voices of Franco Luambo Makiadi, Youlou Mabiala, Les Bantous de la Capitale, or Pamelo Mounk’a could be heard. His novel Tomorrow I’ll Be Twenty returns to this period of childhood, as does his memoir The Lights of Pointe-Noire, a spellbinding ode to the city.

Congo-Brazzaville had of course been home to the French Free Forces in a territory that was beyond the control of Vichy-occupied France, and as a young boy, Alain Mabanckou moved seamlessly between numerous languages—Lari, Téké, Kamba, Munukutuba, Bembe, Vili, Dondo, and French; he would later learn Lingala as a student in Brazzaville, and he would have been more likely to respond inMunukutuba to the question Mboté yangé bokilo. Ngé kelé mboté? (How are you, my beautiful son? What’s the latest?). Alain Mabanckou did not grow up surrounded by a library of books or in a context in which an established tradition of literary excellence would somehow serve as inspiration. “Our problem,” one of Mabanckou’s characters explains, “is that we did not invent printing or the Bic pen, and that we’ll always end up at the bottom of the class thinking we could write the history of our continent with spears. Do you get my drift? And what is more, we have a bizarre accent that comes out in our writing, and people don’t care for it.” But for Mabanckou, words were like moths drawn to a bright light, and he would wander over to the French Cultural Center in search of them, devouring comic books and masterpieces of French poetry, especially Verlaine, Rimbaud, Lamartine—not only for their intrinsic aesthetic qualities, but rather because reciting refrains from these classic French “love” poems impressed the local girls.

Alain Mabanckou began writing poetry, publishing six volumes between 1993 and 2004 (see sidebar). Abandoning his career in law in the late 1990s, his innovative novels, along with numerous short stories, launched him into the international limelight and introduced him to new audiences through translations into more than fifteen languages. He has been described as “one of Africa’s greatest writers” by the Guardian, as “the Prince of the Absurd” by the Economist, blurbed by Salman Rushdie, and prefaced by 2008 Nobel prizewinner J.M.G. Le Clézio, who writes: “What captures our attention and moves us is his perspective on the madness and contradictions of postcolonial society.”

Beginning with an exploration into the postmigratory experience of young Africans in Paris in Bleu Blanc Rouge (1998; Eng. Blue White Red, 2013), Mabanckou’s novels have engaged with a broad range of themes, including childhood, civil conflict, child soldiers, memory, postcolonial history, folktales, travel, displacement, and racism, on each occasion taking his readers on new literary adventures.

He also produced a remarkable translation of Uzodinma Iweala’s best-selling novel Beast of No Nation (Bêtes sans patrie, 2008) and has authored five works of nonfiction, beginning with a book on James Baldwin, Lettre à Jimmy (2007; Eng. Letter to Jimmy, 2014). “Thanks to Baldwin,” Alain Mabanckou has stated, “I understood how France was treating African Americans and Africans. France would consider African Americans as Americans but would not consider African immigrants as French.” These are questions to which he has often returned, notably in L’Europe depuis l’Afrique (2009), Écrivain et oiseau migrateur (2011), and Le sanglot de l’homme noir (The tears of the black man, 2012), in which he turns his attention to the long and complicated history of race in France while also challenging ethnic minorities in France today who continue to cling to mythic notions of African identity and tradition.

In recent years, he has been appointed Chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur (2011), a finalist for the Man International Booker Prize and Premio Strega Europeo Italy (2015), and the 2016 Puterbaugh Fellow.

This Miliki, from the Lingala word that means the individual of the “country,” also signifies “Europe,” where the milikiste has elected to venture abroad. “But in the end,” he asks, “Who am I? You won’t find the answer in my two passports, the one Congolese and the other French.” Born in the Congo, longtime resident in France, Alain Mabanckou joined the faculty at UCLA in 2006 and is professor of French and Francophone Studies, teaching courses on African, African American, and French literature as well as creative writing workshops in French. In 2016 he was elected to the Chair of Artistic Creation at the Collège de France, France’s renowned higher-education institution established in 1530 by King Francis I, and is the first writer in the history of the institution to hold this position—“a tremendous responsibility,” he pointed out in his inaugural lecture, “since I am not a professor who became a writer, but rather a writer who became a professor thanks to the United States.” Acknowledging his gratitude to the United States, he would be the first to recognize the paradoxical nature of this situation and the way in which it serves to draw attention to the current political climate and exclusionary policies in France, given that its capital, Paris, had once been a refuge for such inspirational authors as James Baldwin and Richard Wright, who fled segregationist practices in America. Mabanckou therefore conceived of this opportunity to “appeal for African studies to occupy a more prominent position in France, not in a handful of marginalized universities, not in a handful of underfunded departments, but rather in a more significant way that would improve the understanding of how France was yesterday but more importantly what it has become.”

In many ways, this process of rethinking the global landscape of writing in French began with the kind of thinking we find in his article “La francophonie, oui; le ghetto, non” published March 19, 2006, in Le Monde newspaper, in which he argued that

To be a francophone writer is to be a repository of cultures, a whirlwind of universes. To be a francophone writer is to benefit from the heritage of French literature in general, but it is above all to bring a personal touch to a harmonious whole, one that dissolves borders, erases race, reduces the distance between continents in order to achieve a fraternity in both language and the universe. The francophone family is on its way. We will no longer come from such and such a country, from such and such a continent, but rather from a language. And the proximity we share as creators will simply come from a common universe.

This article provided the architecture of the 2007 manifesto “Toward a ‘World Literature’ in French” (published in English in World Literature Today in 2009), to which he was one of the forty-four signatories, and in which it was claimed that “The center, from which supposedly radiated a franco-French literature, is no longer the center. Until now, the center, although less and less frequently, had its absorptive capacity that forced authors who came from elsewhere to rid themselves of their foreign trappings before melting in the crucible of the French language and its national history: the center, these fall prizes tell us, is henceforth everywhere, at the four corners of the world.” Indeed, many of the arguments that were so central to the conversation at the time are to be found in Mabanckou’s contribution to this current issue, “‘The Song of a Migrating Bird’: For a World Literature in French” (online).

These and analogous statements are to be inscribed in a broader framework that has seen Mabanckou emerging as an incontrovertible figure in a range of cultural, political, and social debates. On May 5, 2015, he was selected by PEN America, an organization founded in 1922 to promote literature, freedom of expression, and human rights, to present the satirical weekly newspaper Charlie Hebdo with the PEN/Toni and James C. Goodale 2015 Freedom of Expression Courage Award, “an opportunity,” Alain Mabanckou underscored, “to pay tribute to the courage of the journalists

who, at the expense of their lives, had fought for freedom of expression.” More recently, he has denounced the longstanding African dictator Denis Sassou-Nguesso of the Republic of the Congo for revising the constitution as a way of orchestrating his victory in the 2016 presidential elections, thereby extending his thirty-two-year rule.

As is repeatedly said of Mabanckou, he wears many hats. His novels Broken Glass and Black Bazaar have been adapted for the stage, he is busy at work on a screenplay of the latter, and Lusafrica / Sony Music released two CDs for which he wrote the lyrics and music. These feature world-class performers and musicians such as Modogo Abarambwa, Sam Tshintu, and Souleymane Diamanka. Mabanckou’s work is strikingly original, constantly renewing itself and providing readers with unexpected twists and turns. In a conversation at a local bar, one character in the novel Broken Glass recalibrates the now-famous statement expressed by the Malian author Amadou Hampâté Bâ in 1960 and that has shaped the contours, scholarship, and reception of African literature for generations—“In Africa, when an old person dies, it is the same thing as a library burning”—suggesting instead (albeit in a severely inebriated state), “Well, that would depend on which old man you were listening to!”

Whether dealing with fashion, music, language, colonialism, contemporary immigration policies, gender relations, masculinity, or globalization, Alain Mabanckou’s work can be qualified by a broad spectrum of avant-gardist qualities: linguistic experimentation (whole novels without punctuation), dismemberment of syntax, playfulness, humor, the combination of genres and registers, remapping in the process the parameters of literature, creating a world—the world according to Alain Mabanckou, in which Le monde est mon langage (The world is my language), the title of a new book of essays published by Éditions Grasset in 2016.

Postscript

In 2008, in Bamako, the capital of Mali, at the Étonnants-Voyageurs International Literary Festival, a boy no older than fifteen approached Alain Mabanckou after he had given a reading. Carrying a ream of paper—almost two hundred pages of double-sided handwritten text—the young boy who could not afford his own copy of the novel Broken Glass had visited the French Cultural Center every day after school over several months and transcribed (“borrowing” paper from the center’s copy machine) the entire novel. . . . As Mabanckou autographed the boy’s manuscript, one could not help but observe the tears welling up in their eyes, each one recognizing something in the other, something that could not be spoken at that point, words that would only come later in Tomorrow I’ll be Twenty, The Lights of Pointe-Noire, and Petit Piment . . .

Los Angeles