The Bath

After multiple catastrophes and faced with the pandemic lockdown—the pain of fear, of austerity, and of abandon—a woman needing to feel loved and eroticized finds that the closest thing was water slipping down her body, running down her curves, cleaning her off as it caressed her.

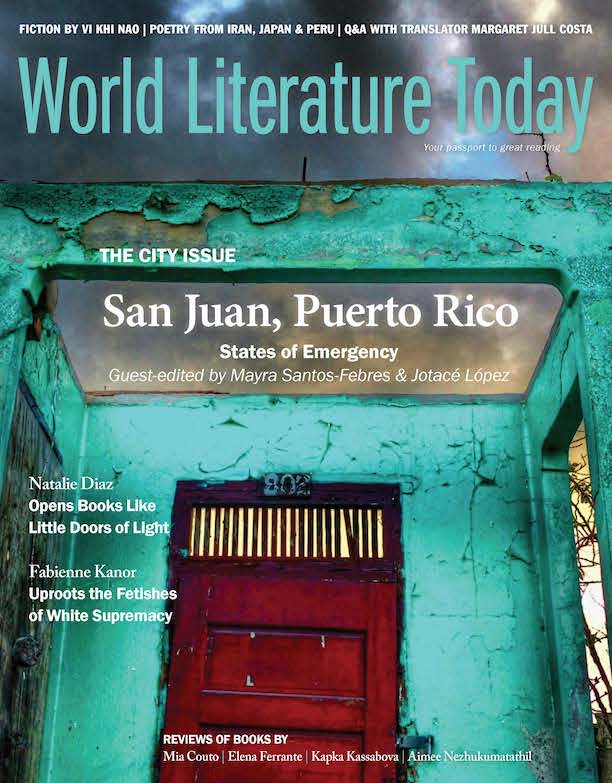

To Puerto Rican storytellers, for resisting and continuing to tell our story

To my friends: Nicole, Carmen, Marilí, Sylma, Pluma, Heidi Anne Vera, and Natalia

The shower seems to explode and water bursts out, warm and with good pressure. Lola closes her eyes so that it runs from her forehead to her cheeks; she caresses her neck enjoying each drop. Some years ago, that same shower was dry for eleven months.

* * *

Today I must wash my hair. That’s two and a half gallons; I cannot waste three.

Unhurriedly and precisely, she would pour water in a bucket destined exclusively for personal washing. She would take advantage of the water with shampoo to wash her body as well. She was in a sort of small bathtub. The water that fell served her to wet and wash cleaning rags or to flush toilets. At some moment of desperation, she even used it to do the dishes.

Walking to the closest oasis wasn’t as difficult as walking back with the full gallons. Her friend Blanca loaned her a shopping cart so she could get more. Then she met Ignacio, a neighbor who would fetch water to supply the neighborhood. He was Dominican, recently arrived from Santo Domingo, where he lived in austere conditions, but much more comfortable than in “Puerto Rico se levanta” after Hurricane María.[i] He lived alone, and was rapidly introduced to the neighborhood by the committee that had been waiting for him for a long time. Lola found him very handsome, but she could not stand his machismo. The way Dominicans and Puerto Ricans flirted was very different. Lola still found no way to reconcile the two. For example, Ignacio sometimes made gestures that made her seem too exposed. He also laughed exaggeratedly and spoke very loudly to her, attracting the neighbors’ attention; that, without a doubt, chased away the desire to connect with him. And besides, with the lack of water and the constant heat, who would want to get intimate? She did; she wanted to get intimate, but since María, all of that changed. The day went by getting water or ice, getting food, and deciphering how to cook it on a camping stove. By five, she had to have bathed because it was impossible in the dark, and she didn’t have candles to spare.

At some point, Lola posed for a photographer. She came out on the front page with her unruly hair, flip-flops, and shorts, sweating, sad, with a gallon of water in one hand in a very long line. Even if she seemed to be alone, Ignacio, doña Puruca, and Andrés were there at a distance, talking about the “dry law” that prohibited the sale of alcohol, the lack of water, and the traffic lights not working. Lola held the bucket in front of her as an offering. She was sick of the spectacle of so many deaths, of so many promises of action; she looked at the photographer, questioning his presence there. Now, every time she sees the image, it seems that she looks like a child, as if waiting for her mother to come get her in kindergarten. There is a similar photo, from her birthday. Her mother was late because of a mishap with the cake. Lola greeted her with sadness, her backpack in the front, like an offering; her mother had to take the picture.

In that way, she seemed to be testifying about her discomfort. Her apartment is on the fourteenth floor, and without electricity, she must bring the water up the stairs again and again. Sometimes Ignacio helped her, saying it was his opportunity to see her ass moving from side to side on the stairs in front of him. She took advantage of his hard labor, answered jokingly. Then one day they devoted themselves to kissing and exploring each other’s bodies without worrying about their odors. The sex, although unfortunately mediocre, gave a certain normality to daily life. Then they bathed and wasted five gallons of water. Ignacio left happily while Lola was unsatisfied, mortified at having wasted all the water that that had been so hard to carry upstairs.

The water she used to wash clothes was also used to water the plants on the little balcony that had become her room. It was cooler and gave her a feeling of closeness to nature that seemed to have caught fire. The only upsetting thing was doña Puruca’s intercessions—she lived to the right side of her—or don Rafael, who thought it funny to invite himself over to pass the heat of the night with her. But the lack of electricity, and her balcony, also made her remember camping on the beach, where she would see shooting stars. The sky, far from the buildings, extended unscathed, but also gently, with thousands of millions of stars looking out for her dream state and her solitude.

After a shelter-in-place order of almost one month, normality was imposed on October 19, 2017. Lola seized the opportunity to go to a friend’s bar. She spent four gallons of water in her bath. But even then, she smelled. Hand washing and hanging clothes to dry inside the little apartment didn’t allow for the clothes to dry properly. Her whole building seemed to be in an eternal celebration because the neighbors hung their clothes out to dry, as if hanging flags from their balconies, but Lola preferred to hang them inside to keep her balcony free. She would have used five gallons for her bath if that would have meant she would stop smelling musty. Girl, you should have asked me. In the Loíza street laundry they have dryers. But Lola spent her money that night.

* * *

She stepped back to look in the mirror she has in the shower. Now, three years later, she can see numerous wrinkles on her face and white hair mixed in her mane that get more intense as they grow. Why color her hair if she can hardly even go out to take out the trash? Who cares if she attends her work meeting with the camera off and nobody can visit her!

In between each catastrophe she can remember a lover: Ignacio after the hurricane and José, an electrician who helped her rewire her electrical system after complications from the tremors in January. He had recently gone to Atlanta to live with relatives. His visible participation in the protests about the country had reduced his opportunities of being hired for work.

* * *

These protests, in particular those of the summer of 2019, made her understand the revolutionary hymn: “ven, nos será simpático / el ruido del cañón” (come, embrace the kindness of the canon’s roar). How could such noise be kind?

She arrived early with her friend Isabel. They parked close to the monument in honor of the police on Constitution Avenue. This monument had been defaced on two occasions. Once, by the Colectiva de Mujeres y Aliades (Women and Their Allies Collective), which threw red paint on the base of the obelisk to denounce gender violence and the government’s inaction. The second time, Luis made some plates with pictures that are very similar to those that decorate the obelisk but that, instead of showing emblematic images of heroism, present police brutality in close-ups. Both operations used the same tactic—people stood guard at each side street that led to the monument. This took place at three o’clock in the morning. In the case of the paint, it was an issue of pedaling and throwing three cans of paint using all their strength. Then they moved to Puerta de Tierra and went out to Miramar, where they got together with the rest of their companions.

The case of the plates required more precision, a small kitchen stepladder, tile glue, and time. The four plates were all ready with grout and separated with plastic to protect them. They were heavy and required careful handling. They had been done so that it was difficult to notice the change in the images unless you got up close. Luis had earphones on, and his companions were on the line on a conference call, telling him if he had to abort the mission. Fortunately, he was able to finish the whole thing and wipe the grout off the corners. Three days later the newspapers covered the event using the epithet: vandalism. They calculated that the damages went as high as fifteen thousand dollars. However, in academic circles the intervention was being compared to Bansky’s, and in others, they were looking for the author of this act of “individual heroism.”

Blanca arrived directly at Plaza de Armas to meet up with Isabel and Lola in Old San Juan. The streets were full of protesters, and you could hear the phrase: “Ricky, renuncia y llévate a la Junta.[ii] Ven, nos será simpático / el ruido del cañón.” Late into the night Pao asked if someone had gas, while pushing a trash can to light it up and turn it into a barricade. “Chorro de cabrones” (assholes), they would scream, throwing rocks. The explosions of the tear gas and the chants of the people screaming, “Somos más y no tenemos miedo” (There are more of us, and we are not afraid), Lola found very, very kind.

* * *

Showering after coming home from the outside world. She takes her shoes off in the first quadrant of her living room, throws the gloves out in the trash can that is right outside the entrance, walks three steps and places the mask on the vaporizer to disinfect it, and from there goes directly to the bathroom. Lola undresses carefully, puts everything in her laundry basket, which has a plastic bag to isolate the clothing. She then lets her hair loose, which she had in a bun, like a ballerina. She chose the most fragrant soap because she couldn’t spend money on perfume. She has to limits herself to the bath and deodorant. There is no money. There is no money. There has been no money for a long time. For her, perfume is like lingerie: it makes her feel sexy. She substitutes it for soap that is ridiculously fragrant, not sexy at all, but she has no other choice. In the end, all casual contact has been penalized. Faced with the pandemic lockdown, the pain of fear, of austerity, and of abandon, she needed to feel loved, desired, eroticized. The closest thing to that was the water slipping down her body, running down her curves, cleaning her off as it caressed her.

Lola started to dry off in the shower. She looked at her cell phone and wrote her friends: “I don’t know why they insist on saying ‘invisible virus,’ as if there were viruses you could see in plain sight.” Blanca doesn’t miss an opportunity: “You are philosophical today, Mama.” Lola continues: “And what does one do to connect in the middle of all this confinement?” Isabel responded: “Instagram?” “It sucks, so much shit and I am stuck here. And then I’ll be dead.” Blanca intervenes: “Girl, take a chastity vow, for what’s left.” Look, I’m going to use the audio, because I’m doing stuff with my hands and writing takes time. What I want is a lover to share my loneliness. . . . Minutes later, Isabel writes: “Lola??? Did you feel the tremor?????” Shit, I hit myself real hard. Ay, it hurts ¡Ostia! I’m bleeding. “Girl, where did you hit yourself?” “Lola” “Put Lysol on it” “@Blancurria stop fucking around, l am calling her, and she doesn’t answer” “drama queen” “she doesn’t answer.”

A few minutes later, Isabel calls Blanca. Girl, she doesn’t answer, I’m worried. The curfew bell went off, we can’t go out to see. Do you have the number of the lady that lives next to her? What’s her name? Puruca?

None of them had a way of reaching Lola, nor anybody close to her. Isabel ignored the shelter-in-place restrictions and went out as fast as she could; she got Blanca, ignoring social distancing as well. They were both masked and gloved, moving in the direction of Lola’s house in Bahia. Some bored cat roamed the deserted and unkempt streets, while the silence gave out shadows of the apocalypse. Close to Lola’s house, a patrol car stopped them, but when they explained the nature of their outing, the officers accompanied them to the apartment.

Lola’s apartment complex was subsidized housing, where hundreds of people lived and, because of the way it was built, was safer in case of earthquakes. Yet, because her apartment was on a high floor, the tremors felt bigger and stronger. She wasn’t responding to the phone or the door. The neighbors came out immediately, and the police instructed them to uphold the protocols of Executive Order 2020-033. They went back to their homes, but not entirely; they left a crack to look through. After having been locked up for a month, the presence of the police was somewhat of a sensation.

The agents then forced the door. There was no one in the living room, no one in the hallway, no one in the room. In the bathroom: Lola, half-naked, surrounded by blood coming out of her head. Next to her body there were visible tile fragments of the shower, with a rusty rod gratuitously sticking out. Crying and confused, the friends were interrogated. They looked in Lola’s cell phone for her sister’s phone, her only living relative. When they opened the screen, they found the chat, which read: “she doesn’t answer.”

Translation from the Spanish

[i] Translator’s note: “Puerto Rico se levanta” literally means “Puerto Rico rises.” It was a slogan used by the government after the hurricane.

[ii] This was the slogan of the summer 2019 protests that resulted in the governor’s resignation. It literally means “Ricky resign and take the Fiscal Control Board with you.”