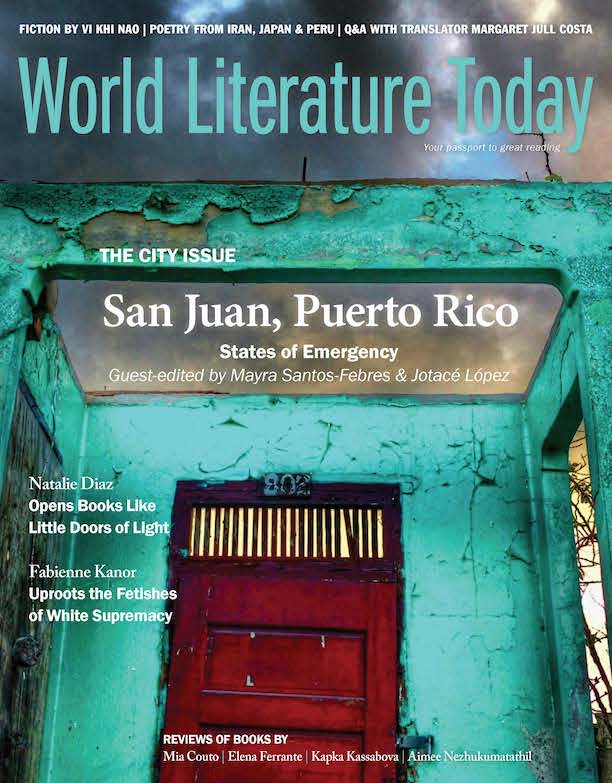

San Juan: A Prolonged State of Emergency

The state of emergency is the exception, the overturned routine, the searing pause, the lost tranquility. You might think that it is just a readjustment of daily routines, but it is not. It is obvious that there are situations that allow governments to evade laws and silence rights for the common good. To do this they present people as a huge, homogeneous, and abstract mass. However, the decisions made by those who were once elected affect real people with particular situations. In this way, individuals not only have to face—or rather survive—the situation generated by the state of emergency, but they must also deal with laws and regulations imposed for the moment. Then each person is forced to weigh the chances of survival. The negotiations that each one makes with oneself are continual. To survive, in this case, is to admit fragility as a strategy to defend life.

The circumstances in which life occurs are fundamental for the development of any country. The responsibility of governments is to provide the optimal conditions for their sustainability. From this perspective, the various administrations that have governed the colony of Puerto Rico have failed. In 2014 an economic crisis began. The United States government in 2016 passed the Puerto Rico Oversight, Management, and Economic Stability Act (promesa), which established a financial oversight board in charge of managing the finances of the entire island. Part of its financial adjustments for 2016 through 2026 include cuts in public budgets—in the health plan, pensions, education—as well as in other areas in order to repay bond holders. These measures have increased the poverty and precariousness in Puerto Rico. In this scenario, living conditions are left aside, and the bodies are just numbers that translate into money. That is, the body that has been directly affected by the decisions made by Puerto Rican and American politicians. A state of emergency prioritizes money over human life.

Inefficient governments, natural disasters, and, recently, the pandemic are problems that are experienced in any country. However, the scene of resistance and struggle in the midst of each state of emergency is always the bodies. To speak of a constant state of emergency is to speak of the vulnerability of bodies. It is not about resigning the breath, or calibrating the pulse with the edge of the knife, but about transforming and adapting, being ready for change. This has been the experience in San Juan, the capital of Puerto Rico. This city, located on the north coast of the island, has been the scene of catastrophic hurricanes, major protests, and the pandemic.

To speak of a constant state of emergency is to speak of the vulnerability of bodies.

At the beginning of this twenty-first century, different events have emerged that have affected life globally. Climate change is perhaps one of the most important factors of change. Melting icebergs, hurricanes, uncontrolled forest fires, long droughts, floods, and temperature changes in the oceans force human beings to reformulate their consumption patterns, their diet, ways of building—in short, to rethink our ways of inhabiting the planet. Within this context, the Caribbean, Puerto Rico, and San Juan faced one of the most powerful hurricanes in history. That hell of wind and water exposed old administrative and governmental problems that the island has had since the twentieth century. The tragedy was not only in the landscape but a deep trauma embodied in Puerto Ricans.

On September 20, 2017, Hurricane Maria passed through Puerto Rico and changed the lives of Puerto Ricans. The winds of 125 miles per hour, the 40 inches of rain, 100 percent of the population without electricity, 60 percent without drinking water, destroyed houses, and isolated communities were part of the devastation caused by this Category 4 hurricane on the Saffir-Simpson scale. The inability of government-privatized hospitals to deal with the emergency, lack of leadership, disinformation, and hunger were part of the state of emergency in 2017. There were families without electricity or drinking water for several months. The official government figure claims there were 64 deaths; however, a Harvard University study estimates that number to be at least 4,645. As of today, it remains unknown how many people actually died. A Category 4 hurricane not only disrupts geographies; it also affects the ways in which people inhabit their existence. Bodies are always the setting.

As if that were not enough, months after the hurricane, supplies were found in various parts of the island that had never been distributed to the victims. Expired food, water bottles damaged due to being exposed to the sun—no one within the complicated and absurd government bureaucracy claimed responsibility. Excuses piled up, fueling the outrage of Puerto Ricans. When all is lost, the only thing that remains is dignity. Precisely that dignity was trampled on by government officials. The publication of 889 pages of chat messages between the governor and his inner circle revealed their contempt for Puerto Ricans and the low importance they attached to those killed by Hurricane Maria. In the chat they made fun of those killed by the hurricane and made sexist, homophobic, and misogynistic comments about press reporters and voters of their own party, politicians, and celebrities. The people’s indignation inspired a wave of militancy. During the summer of 2019, hundreds of thousands of people marched on the streets of San Juan demanding the resignation of Governor Ricardo Rosselló. The protests were met with police violence and tear gas, but a single request unified the voices of the protesters: demanding the resignation of the governor. At the end of the summer, people celebrated his resignation.

By the end of 2019, the full recovery of the island had not yet occurred. However, life continued. On January 7, 2020, at 4:30 a.m., a magnitude 6.4 earthquake shook the island. From its epicenter in the southern town of Guánica, the quake was felt throughout the island. The electrical system was affected again, leaving the island in total darkness for several weeks. Hundreds of families had to find shelter after losing their homes. Others, despite not having suffered losses, were psychologically traumatized. It was common to go through the streets and see people improvising shelters in patios, parking lots, wooded areas, or anywhere in the open. Due to aftershocks, this situation lasted for months.

The open sky without a roof—full of sun, clouds, or stars—became a menace. Now, being out of the house is dangerous due to the pandemic caused by Covid-19. This situation brought a radical transformation in all areas of society. Confinement and social distancing have become routine. Many people have lost their jobs or have been unable to work. Others did not have the necessary savings to support their family. But beyond the economic aspects, we have to add the anxiety, depression, and despair caused by confinement. Faced with this panorama, an investigation arose to oversee the purchases made by the government of “fast tests.” Furthermore, the government has failed to develop a system for establishing clear statistics and a contact-tracing system. Governor Wanda Vázquez, successor to Ricardo Rosselló, decided to relax the restrictions and the curfew, which resulted in a spike in positive cases of Covid-19. The lack of clear and truthful information when making decisions has affected the island. According to the governor, the increase in cases is not the government’s fault. When compounded by poor governmental decisions, viruses have dangerous consequences.

The hurricane, the earthquake and aftershocks, government mismanagement, and the pandemic have generated a continual state of emergency. Within this state of emergency, individual sufferings become reports, comparative tables, and figures. While such information fulfills an analytical function, it is often forgotten. However, beyond statistics, official speeches, and news reports, there is literature. Literature is like a crucible where memory and aesthetics combine. It orders the chaos of experiences and allows us to build a collective memory. The experience of bodies is transformed in written discourse.

The constant fight against precariousness and poverty leaves traces on these narrated bodies.

The selection of texts gathered in this dossier presents the nuances of human experience in what we are calling a state of emergency. Each of these texts presents a variety of facets of the emergency. However, this writing does not detract from the events it presents; on the contrary, it places them in communion with the rest of the experiences lived in recent years in San Juan. Each short story, chronicle, and poem speaks about bodies that have been affected and transformed by the continuing state of emergency. The constant fight against precariousness and poverty leaves traces on these narrated bodies. These traces are what allow us to identify the particularity of each experience as something unique and not as a set of statistics.

South Beach, Miami