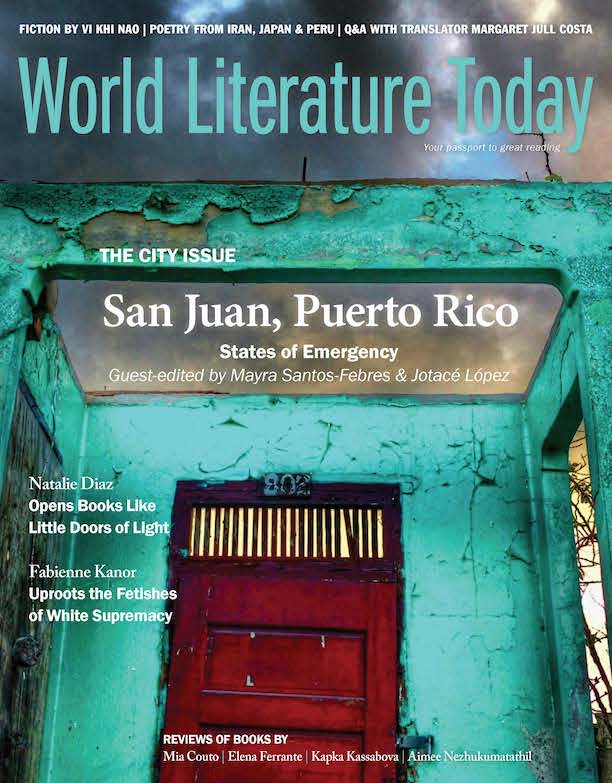

Déchoukaj’: Uprooting the Fetishes of White Supremacy

A writer traces how the murder of George Floyd is continuing to arouse people in cities everywhere, including her own mother in Martinique.

Sa ki ta la rivyè pa ka chayé’y. What belongs to you, river can’t carry away. Everyone in the French Antilles, labeled French, has grown up with this saying. It is part and parcel of their beliefs, their customs; it is in their genes. It has fashioned their ways of being, thinking, dreaming, examining history, of triggering or idly waiting for their fate. To grasp how far the saying can go, you must move the words around, and you will conclude that what belongs to you belongs to no one else. The right to own and control your body, your history, your culture, your luck, your economy, and your land ought to be a universal principle, a natural human right that no one can attack with impunity or without repercussions. Those who have plundered will be brought to book. Those who have been plundered must have their possessions restored to them. Sooner or later.

The murder of Mr. George Floyd, and the protests that this murder—caught live as it was being committed by a government employee—is continuing to arouse, have given us the opportunity to challenge the Creole folk saying. In cities everywhere, streets have been filled with raised fists, demanding justice and redress. Demanding the respect that is owed but that has been confiscated for centuries. Denouncing and dismantling the machinery of a world built on institutionalized racist practices: an old, old world that has never purged its sin of granting privilege to some and condemning others to timeless suffering.

But what belongs to you, river can’t carry away. In Antwerp and in Bristol, in Brussels and Pretoria, in Nashville, Richmond, St. Paul, Boston, Washington, and elsewhere, communities whose rights have been scorned have taken to the streets, together with their allies, in order to uproot statues. They have fallen, the fetishes of white supremacy. They too are threatened with death or knocked to the ground, these men of marble, stone, or bronze, heirs of a slave-owning or colonial past and heroes of patchily recorded national sagas that all too often consist of blatant lies.

In Martinique it was Victor Schœlcher, consecrated founding father of the abolition of slavery in all the French colonies and possessions, who drew the wrath of the activists on May 22, the day on which the abolition of slavery is commemorated.1 In images streamed live online, the execution of the colossus is ritualized.2 The militants place a rope around his neck. They insult him, flog him, knock him off his pedestal, and kick him repeatedly until the French politician, who died in 1893, expires for good and returns to dust. Schœlcher is virtually a household name in Martinique; it is that omnipresent. It is, notably, the name of a school, a town, a commune, a street, and a public library that has been classified a historical monument. It is the name that generally springs to mind when the question of the second abolition of slavery is discussed. It is the name people know because it is the only one that the official version of History has retained and passed on to them. In Martinique, we don’t speak of the independence of human beings but of the abolition of a system. Which presupposes, if we stick to the etymology, the intervention of a subject that wields power (in this case, France) and the passive presence of an inanimate object (slavery).

For my Martinican mother, who returned to her native land upon retirement after forty years of good and faithful service to France, this Schœlcher, whose name she systematically garbles when she says it, is the liberator of her oppressed Black people. My mother ignores the fact that her benefactor, like most of the politicians of his era, approved of the continued possession of the colonies, of the right of France to dispose of lands that did not belong to it, and of the expansion of French cultural values to these occupied territories. She does not know, my mother who left school at the age of fifteen, that the so-called definitive abolition which Schœlcher officially initiated did not in any respect lead to the end of the old world or of capitalism. Compensated for having lost their workforce,3 the former slave owners, protected by France, continued to prosper, invincible and firmly planted on their pedestals.

What these rebels are demanding, in the end, is to obtain what belongs to them, that river can’t carry away.

My mother, who has never taken to the streets to protest against anything, does not know, either, that for centuries a small number of her people have been fighting against French cultural alienation and the white domination incarnated in the French Antilles by the white Creoles. It was those militants who on May 22 decided to put an end to Schœlcher’s legacy, not in order to sully the memory of the Republic, as certain high-ranking politicians hastened to claim, or because they think that the hero with the garbled name accomplished nothing of worth, but because they do not think that particular totem represents them.4 What they want to honor is the silenced memory of their rebel ancestors: those enslaved men, women, and children who struggled to survive and struggled to break free, with their sweat, their strength, and their faith. What these rebels are demanding, in the end, is to obtain what belongs to them, that river can’t carry away; it is the right to tell their history in their own way, to tell the story of all the Black warriors who forged that history, the right to teach it in their schools, the right to show it and celebrate it in their public space, and the right to no longer be invisible.

I look at the faces of Schœlcher’s uprooters. They speak openly and take responsibility for what they have done. I can see hope in their eyes but exhaustion, too. They have been tired for so long, for as long as this world has refused to change. They are so tired it makes you tired, just talking about it. On June 17, 2020, two weeks after the huge rally held outside the Paris tribunal against racism and police violence in France,5 the Haitian producer and filmmaker Raoul Peck declared he was “tired of being the one who has to make the effort to understand, the effort to explain, the effort to be magnanimous in the face of your ‘innocence.’”6 He was addressing the country of France where he has been living for over fifty years. He was denouncing its “respectable paternalism” and the racism it has failed to own up to, “every bit as brutal and effective” as the one that suffocated George Floyd. Tired of seeing History always going in the same direction, always repeating itself, the director of Lumumba and I Am Not Your Negro admitted to how disenchanted he is feeling. That morning, before picking up his pen, he had burst into tears.

Raoul Peck’s words took me back to June 2017, when I was invited to a conference in Port-au-Prince to hear Angela Davis. It was not a speech she gave, it was a lament. Thinking of her community, with its rights constantly violated, and its bodies that did not die of natural causes, Angela Davis confessed that she, too, was tired. We are tired, she said, of seeing our people get killed, of seeing them die, we are tired of mourning our dead.

We are tired, Angela Davis said, of seeing our people get killed, of seeing them die, we are tired of mourning our dead.

I too have felt tired. I too have had tears in my eyes.

We die in Minneapolis because a policeman, a government employee, has the right to kill a Black man in America. We die in Haiti because “the debt of independence” imposed by France paralyzed the economy of the island for over a century.7 We die in Sierra Leone, in the Democratic Republic of Congo, in Ivory Coast, and elsewhere, because fewer public schools and hospitals are being established there than pillaging multinational corporations. We die in South Africa because the wounds inflicted by apartheid have still not healed. We die unburied in the Sonoran desert and in the depths of the Atlantic because what belongs to everyone—the planet and the right to move about on it freely—belongs only to a handful of privileged people. We will end up dying in Guadeloupe and Martinique, because the soil there, spiked with Kepone, contains enough of the substance to poison generations to come.8

To write in the flesh, in the bones of a Black woman, is to give an account of all these deaths, and to try to offer healing to those who remain. It is to be a survivor and to wonder, at every instant, how much a word weighs, in this world. These days, I’m tempted to believe that words don’t weigh a thing compared to acts. I have thought that if I could remake myself, could do it all over again, I would learn not to be afraid of dying, I would learn to fight. As a little girl I inherited the virus of inaction. As the child of poor Black immigrant parents, I was scared to death of taking my destiny in my hands, of claiming what belongs to me and that river can’t carry away. When I was little, French people who were no more French than I was would say to me, “Go back to your country!” When I was little, at the white school where I was the only Black, I meekly put up with the white kids messing my hair and making fun of me. When I was little, I got called “Negro” and “caca boudin” and “Brillo pad.” When I was little, I wet my panties when it was my turn to raise my hand and express my opinion in front of the whole class. When I was little, I acted as if all the times my freedom had been taken from me didn’t matter, as if the other kids, the ones who ruined what belonged to me, had every right to do so.

These days, I’m tempted to believe that words don’t weigh a thing compared to acts.

When I was little, I watched how my father—for all that he was a big man—would bend and bow and scrape, hide his accent and his six-foot-two frame and the color of his skin, hide his language and his honor. I saw him disappear behind his complexes and his fears. When I was little I put up with the smell of bleach my mother brought home from the hospital where she did everything a Black woman without an education or a future can do. She smelled of bleach, but it was as if she smelled dirty. When I was little, I was afraid to answer when people asked me what my mother did. And so I would make myself inconspicuous, I would do and think what white-skinned France expected of me. I said thank you, sorry, excuse me, I don’t know, I’m not pretty, I’m not smart, I’m not this enough, I’ll never be that enough. . . . When I was little, I pulled the rug from under my own feet to stand where they wanted me to stand. In Creole, we say yo to mean “they.” When I was little, to me this yo meant white people. I put this yo inside me, and we grew up together.

I am writing to reclaim what belongs to me.

As I watched Mr. George Floyd dying on television, I felt that I had already seen these images. A classic scene, based on familiar dramaturgical elements: on one hand, hatred and impunity. And on the other, force of habit. Force of habit, getting lynched in public, with no one coming to help you. Force of habit, not going to help. What would I have done, what might I have tried, if I’d been on the other side of the screen, among the onlookers? Would I have gone closer, instead of watching, to order the murderer to stand up? “Stand up if you’re a man! Stand up!” Would I have risked my hide to save Floyd’s? What does “risk my hide” mean? What do you get, for not doing anything?

I am writing to reclaim what belongs to me.

Cowardice is a contagious disease.

Anger is benign when it works miracles.

I called my father.

I called my mother.

My father, as helpless as Floyd, did not comment on the murder. My mother, for the first time in her life, was indignant: “Too many people have died. There are too many Blacks getting killed by whites. Now they say you have to take a knee to protest, but racism is in the soil and the air they breathe in the United States. It’s like the virus, they’ll kill anyone, when you’re Black they kill you. No! It has to stop!” If she lived in Minneapolis, she would have taken to the streets to uproot them all: every racist policeman in that town and in all the united American states, the racist whites in that town and in all the united American states, every racist on the entire planet. Then my mother stopped talking, because she was angry, and tired, and her knee was hurting her. She’d spent too many years waxing the corridors of France’s hospitals. Her legs don’t move as quickly as they used to.

My mother, for the first time in her life, was indignant.

I hung up.

Less alone, and prouder. And so, after forty years of services rendered to a homeland that imposed its silence and its heroes on her, my mother had broken her chains. Her no weighed more than any act of abolition, and more than all my words. She had taken Schœlcher’s place. My mother, woman of the people, She-People, was now her own totem.

Translation from the French

Translator’s note: In Haitian Creole, déchoukaj’ is a derivation of the French dessouchage, which means the act of tearing up by the root. Since the fall of the Haitian dictator Jean-Claude Duvalier, the term has gained a political connotation. It refers to the total destruction, by the people, of property having belonged to their despots.

1 Suppressed initially in 1794, then reinstated by Napoleon I in 1802, slavery was abolished for good on April 27, 1848. This new act of abolition was signed by the provisional government of the Second Republic. Schœlcher at the time was undersecretary of state for the navy and in the colonies. In fact, the people of Martinique did not wait for the arrival of the act of April 27 to set themselves free. On May 22, 1848, they took to the streets to demand their rights; this obliged the government of the colony to enforce the act of abolition immediately.

2 Two statues of Schœlcher were toppled on May 22, 2020: the first was located in Fort-de-France outside the former Palace of Justice where it had stood imposingly since 1904, and the second at the entrance to the center of the town of Schœlcher. This second statue was installed in 1965.

3 The 1848 act of abolition stipulated in article 5 that “the National Assembly will determine the amount of the compensation to be granted to the colonists.” One year later, a law was passed awarding 12 million francs in compensation to the colonists of Martinique, Guadeloupe, French Guiana, Réunion, Senegal, Sainte-Marie, and

Nosy Be.

4 Not a single nèg mawon (Maroon) with a name has a square, street, avenue, school, or airport named after them in Martinique. I’m not including the handful of monuments, not nearly as familiar as the statues of Schœlcher, that symbolize the resistance of the enslaved, such as the Tree of Liberty, a work by Khokho René Corail, or The Bench offered by the Toni Morrison Foundation as part of the “Bench by the Road” project.

5 The Vérité pour Adama collective, which was at the origin of this mass demonstration, was founded in the wake of the death of Adama Traoré on July 19, 2016, in a gendarmerie in the Paris suburbs. The young Frenchman of Malian origin had been stopped by the police for an identity check and was taken into police custody. The Traoré family, who have always implicated the police in Adama’s death, have been fighting for four years to see justice done.

6 Entitled J’étouffe (I Can’t Breathe), Peck’s text appeared in the weekly Le 1, No. 301, on June 17, 2020.

7 This debt of independence, which dates from April 1825, obliged Haiti to borrow from French banks in order to compensate the former colonists. The total amount of the debt was set at 150 million gold francs.

8 Extremely toxic to water and soil, and carcinogenic to humans, chlordecone, marketed as Kepone, has been banned in the US since 1976 and was withdrawn from the market in France in 1990. However, to optimize banana production—the pillar of the French Antilles economy—the French state went on using the pesticide in banana plantations there from 1973 to 1993. Experts estimate that it will take centuries for the contaminated soil of the French Antilles to return to health.