Sativa Latitude

A woman, her caregiver, and a daily walk to the edge of a cliff overlooking an estuary.

1

I’ve told Camándula many times to take me to the boulevard via Imperial Street, so I can see the graves at the cemetery when the sun starts to fall and the afternoon wind, lovely this time of the year, moves the clouds toward the mountains. She barely speaks. She opens the gate, sets up the metal ramp, and industriously pushes the wheelchair, no complaints. I have forbidden her to wear hair rollers and flip-flops. She won’t tell me, because she’s shy, discreet, but I know she loves coming to El Morro, passing by the Quinto Centenario Plaza, and staring at the entrance to the bay—the water mumbling against the rocks, the rolls of foam, the seagulls fluttering on the horizon. On rainy days she wears a raincoat and I carry the umbrella. We complete the route no matter what: thunder, hail, or lightning. The doctor recommended it—at least one hour, take the lungs on a stroll, for they fill up with dust; he slides his stethoscope over my curved back, avoiding my bra, the small ulcers around my spine.

When we reach the sidewalk, she changes rhythm, slows down, and if I see that she’s driving distracted, too fast for my taste, I quickly call her attention—what’s the rush, the telenovela is not on until seven. I almost can’t hide the anxiety created by seeing the empty plain, the green grass, the lighthouse escorted by three flags, the walls decorated with moss, the castle’s silhouette, which, on summer daybreaks, seen from afar, bathed by a pale moon reflection, resembles a watercolor painting losing its outlines. One could say that deep in my chest someone opens a can of Coke and the fizz runs uncontrollably through my veins.

Deep in my chest someone opens a can of Coke and the fizz runs uncontrollably through my veins.

At noon I finish my lunch and pray the Angelus while she picks up the dishes and washes them, humming a song—usually Juan Gabriel or Sandro. Rosa, rosa tan maravillosa. Rose, such a wonderful rose. She is efficient and dutiful and has a good ear. Then I remind her of her chores—at four, mama, at four. This means, of course, that making me ready must begin at three—washing my hair, ironing my dress, putting on my makeup, and leaving the house spotless—the floor waxed, the curtains tied properly, the living room glassware shiny, and the bathrooms neat. Let’s just agree that there is nothing worse than sitting on a dirty toilet.

“Dye my hair and put some talc on my armpits, mija,” I demand from her.

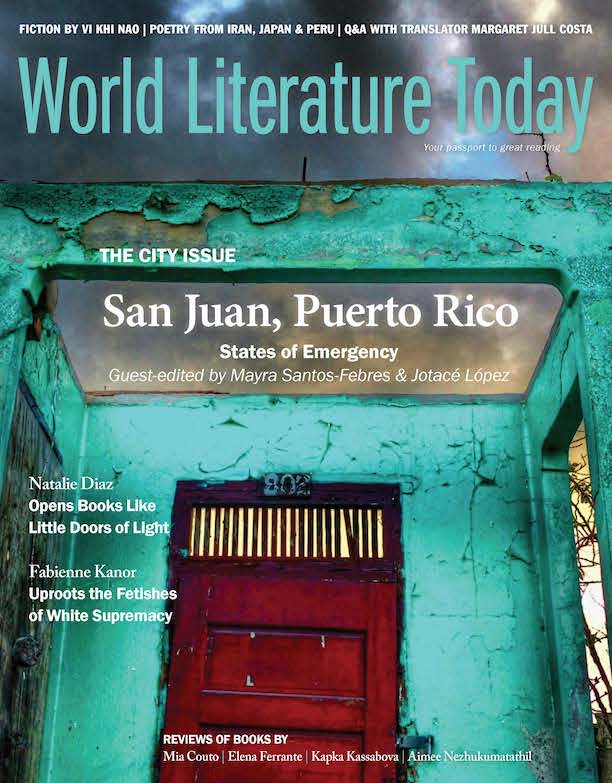

Thus, by the time we go out and step on the cobblestones, all I want to do is enjoy the trip and stop to appreciate the different sizes of the doors, the colors of the façades, the open windows, and the flowers hanging from the eaves as we make our way to the old Dominican convent and the breeze ruffles my white, long hair and invades my lungs, tired of the constant siege of sawdust and naphthalin. The leaden blue ocean brings a fragrance of tanned wood with it, a pleasant noise of sails and seashells that delights us both, although she remains silent, her hair collected in a hairnet and her hands squeezing the handles.

People who exercise every day often acknowledge us. Some raise an arm as a signal of respect, and others offer a mellow smile. It’s part of a routine, I suppose, knowing that, before the evening, the young woman and the lady will pass by, all perfumed and elegant, on the way to the cliff, with her diadem, a pearl necklace, and her purse on her lap. We return all greetings, with courtesy.

I always ask her to stop upon reaching the side of the mental hospital, just on the corner, so I can become enthralled with the marble rotunda, surrounded by niches and burial mounds, leading to the graveyard. I love to examine, calmly, the sleeping pantheons lulled to sleep by the tides—the silence where the underground caresses of the dead grow, among blades of grass and broken glass.

One thing is clear—nothing compares to walking up the gravel road leading to San Felipe castle and sensing, in the distance, the mighty presence of the stones converted into a fortress. Not a shadow nor a tree to take cover, that’s true, and yet here, over the promontory, facing the small island that sheltered lepers, the light never ages and the air remains untouched by the perfume of the earth.

2

I say it and I repeat it—it’s not that I don’t like the place; it just bores me. Such a fuss about that fort, such a tug-of-war, and it’s nothing more than the legacy of the conquistadors, the symbol of European brown-nosers who, upon arriving, took all Indian women to the mountain, gave them the crabs, and, by the way, abused all the Blacks and took away all the gold. The old lady is just like them in her own way—she obliterates everything in her path. She eats the oatmeal cookies and hides the leftovers in the pantry, not to be shared. She prefers to throw away a plate of arroz con salchichas rather than give the scraps to the poor, and she puts old clothes, underskirts, and blouses in the trash. She also is a breeding ground for infections. She has infected me, in nine months, with conjunctivitis, whooping cough, and bird flu. She daubs herself in camphor, she clears her throat like a prisoner in a galley, and she leaves the plastic spittoon in the hallway, waiting for me to pick it up at midnight. All she does is complain, endlessly—you gave the plants too much water, Camándula, you put in too much salt, girl, lower the heat of the bean pot, you slacker.

She has infected me, in nine months, with conjunctivitis, whooping cough, and bird flu.

I said yes because she seemed like a sweet, charismatic old lady, a defenseless granny, and because I fell in love with the ambience of the house. The inner patio, with a cistern at the center, with clay floor tiles and azulejo tiling on the wall, invited me to remain there, in the rocking chair, drinking lemonade while the brightness spread around the fern branches, and the objects, colored red, recovered the warmth they once had at dawn. I imagined myself taking care of her, threshing gandules, serving tea and ginger candy, and I had no doubt—this is my space. There is a felt canopy covering the recao pots leading to the garden, behind which there is a hidden aluminum container full of twenty-dollar bills and marijuana. This is her secret. Before going for a stroll, she eats pot!

I tie my apron over my neck and serve her on some porcelain plates that once were her mother’s—I’m keeping count just in case you want to fool me, she says, and I bring her pea soup, macaroni salad, senenata, and funche. She sleeps her siesta on a recliner chair under a roof fan, snoring, just like a beast in a barn. She must have been, in her good days, quite a woman. She’s tall, robust, and wide-hipped, with a complexion that all the young kids of today would die for, the daughters of concealer and moisturizer.

She must have been, in her good days, quite a woman.

The main room is full of pictures of her. She shows herself whole, beautiful, buzzing with energy. But, of course, her husband bought an apartment for his lover of the month, God knows when, and left her. She let herself spoil. Her many diplomas and university titles didn’t mean diddly squat to her—she let herself fatten in resentment, sugar, and weed. And she broke down.

I couldn’t care less for this matter. There are two types of pendejas—those who fight over a man and those who cry over them. The king is dead, God save the king, and like the divo of Juárez said—I can come back, but I don’t come back only out of pride. In any case, looking at her young, happy figure within these frames made of polished silver, a legacy from her ancestors, and then listening to her tired, slow breath, the sound of sand and stone stuck in her throat, makes me think of a fruit nobody wants anymore, of a cigarette curling away inevitably. We will all end up like this—as dead flowers in a drawer, rejected even by flies. Life is so cruel, goddamit. The rich take time to find this out, that’s true, but do so in the end.

Despite all this, she still is an oppressive hellcat. For a miserable wage, she makes me shine her faucets, rub her toes with aloe cream, brew coffee with a cloth, oil the cabinet hinges, read her poems at daybreak—roll her joints! I comply, of course, indeed, but patience has a limit.

3

Camándula carefully reaches the edge, testing the cliff’s deep silence, and I asked myself, intrigued, what cadence does the flight of doves over the beach have; how do sea urchins roll around among the anemones? Small fishing boats pass by, some fragile longboats full of nets and harpoons, weathering the northern, violent surges. In the distance, in the indigo far point of the sky, the world is clean, and dusk saturates the masts of ocean liners.

Then I feel behind my shoulders her thumbs trembling with rage, and the wheels ceding little by little, clinging to the dry threads of grass. And I close my eyes, ready, and I bite my lips, and a murmur of spikes drowned in mud clouds my thoughts, and I see myself, finally, tied to an anchor at the bottom of the estuary.

Inclined over me, she takes out a lace scarf, emotionless, sullen, and she shies away from the trail, scared by the buzzing of the bees.

“Time to go,” she says, while apathetically pushing me back toward the city.

The streetlights are lit, and the roofs vibrate to the beat of sirens from the ships that leave the port.

“We’ll come back tomorrow, then,” I answered, distant, and I add, “We’ll see if you muster up the courage.”

Translation from the Spanish