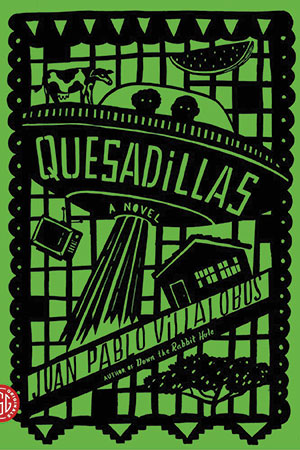

Quesadillas by Juan Pablo Villalobos

Rosalind Harvey, tr. New York. Farrar, Straus & Giroux. 2014. ISBN 9780374533953

Continuing the exploration of Mexico that began in Down the Rabbit Hole, Quesadillas searches for the identity of a place that is anything but normal. Juan Pablo Villalobos invokes the weird and the random as he questions what it means to be Mexican, to be poor, and to be poor in Mexico. His second novel can be read as a picaresque adventure, imparting social criticism through a poor boy’s travels in a decaying country. It can be read as a parody of the magical realism that supposedly characterizes Latin America, condemning this essentialist attitude with absurd magic and realism that is almost too real. Finally, it can be read as a Greek tragedy, with classically named characters in a family that seems destined to collapse.

Continuing the exploration of Mexico that began in Down the Rabbit Hole, Quesadillas searches for the identity of a place that is anything but normal. Juan Pablo Villalobos invokes the weird and the random as he questions what it means to be Mexican, to be poor, and to be poor in Mexico. His second novel can be read as a picaresque adventure, imparting social criticism through a poor boy’s travels in a decaying country. It can be read as a parody of the magical realism that supposedly characterizes Latin America, condemning this essentialist attitude with absurd magic and realism that is almost too real. Finally, it can be read as a Greek tragedy, with classically named characters in a family that seems destined to collapse.

The novel’s protagonist, Orestes (a.k.a. Oreo), reluctantly shares a dilapidated house—and often-scarce quesadillas—with his oversized family. His father swears at the television about Mexico’s corrupt politicians while his brother Aristotle attempts to monopolize their mother’s quesadillas. After a bout of political violence characteristic of 1980s Mexico, two of Oreo’s siblings, the “fake twins” Castor and Pollux, go missing.

At this point, the story diverts into full-scale ridiculousness. A Polish family moves in next door, and Oreo learns from their son the language of class hierarchy. Aristotle suggests to Oreo that the fake twins were captured by aliens, and the brothers go in search of their abductors only to have a falling-out, leaving Oreo to wander the countryside with a miraculous device that can fix any machine with the push of a button. After his return home, he is pressed into assisting his neighbor with the delicate work of bovine artificial insemination. The chaos climaxes with the destruction of Oreo’s home and his father’s madcap effort to construct a new one, at which point the novel’s previous elements emerge en masse and drag the story to its satisfyingly bizarre conclusion.

Quesadillas is fast-paced and colloquial; it is troubling and funny all at once. The story’s balance of the disturbing and the amusing results in equal parts from its sardonic social commentary and from its young narrator, Orestes. Oreo is cynical, seeing family and affection in terms of quesadillas. He is also endearing, constantly hoping for normality in a place that is inherently abnormal. Rosalind Harvey’s English translation—while noticeably more British than American—maintains the verve of the original and offers readers a chance to realign their perceptions of Mexico and Mexicans. Quesadillas is an unusual and important novel that deserves to be read.

Arthur Dixon

University of Oklahoma