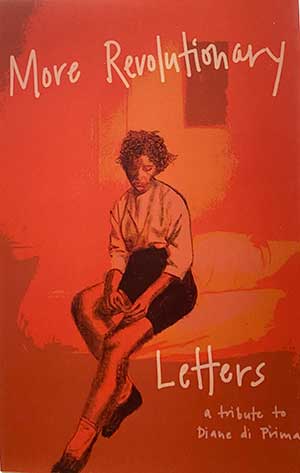

More Revolutionary Letters: A Tribute to Diane di Prima

Denver. Wisdom Body Collective. 2021. 78 pages.

Denver. Wisdom Body Collective. 2021. 78 pages.

WISDOM BODY COLLECTIVE has released an anthology of thirty-three poems and letters addressing themes Diane di Prima outlined half a century ago. All these featured poets saturate the page with their tributes to di Prima’s work, whose sense of kinship has been these featured poets’ actual kinship as the collection’s leitmotif. Di Prima’s love of revolution is their love. More Revolutionary Letters offers readers a fresh and revelatory look at the legacy left by di Prima’s Revolutionary Letters at a crucial time on this planet. Here we have poetry that presents the full gamut of original themes: pandemonium and poverty, including various approaches with a generous sampling of compelling voices.

The anthology’s title charts the course of di Prima’s living poetic influence on today’s poets, some transnational from informal traditions, while many featured writers are constituents of the Jack Kerouac School, all responding in sympathy to di Prima’s oeuvre in a spirit of revolutionary epistles by offering protean ruminations on the late poet’s work. In this way, the anthology can be read as an intertextual body of work. The revolution di Prima identified is alive here as the world’s perverse leanings toward war and opaque totalitarian tactics used to subdue the avant-garde are dismantled in a language no one but the poet di Prima could expound. Here we have the language in new vestments.

The poems call to mind the preface to Wordsworth’s Lyrical Ballads, “to describe [incidents from common life], as far as possible in a selection of language really used . . . to throw over them a certain coloring of imagination.” Likewise in an intertextual spirit, the poems incorporate informant calls and responses with di Prima’s poetry. In the opening poem, Andrew Schelling writes: “(wolf howl mourn here, sign / Diane wolf paw print / end needless killing critters forever.”

When I decided to write a review without having read Diane di Prima’s Revolutionary Letters, I was reminded of what the poet Fran Winant wrote: “what I don’t know now / I still can learn.” During my third reading, it was in Ana Anu’s “Hiding in the Bush” that I suspected an allusion to di Prima’s “Annunciation,” in which the latter poem’s narrator imagines the immaculate conception of Jesus Christ as rape, while later, Obinna Chilekezi’s “Living but Dead Humans” missive amounts to a declaration of a revolutionary’s freedom.

Wisdom Body Collective’s tribute strays far from a traditional assemblage of academic verse as we reckon with “the banishment of myopia” Ada McCartney outlines. These poets are bearing themselves with indefinable experiences in a commanding quaver that leaves the reader hungry for more. We want it; the poets here give it “because of what thrusts from our throats out of control,” indeed as I read aloud to myself outside my pitched tent in a California field while the universe screams, the reader screams, di Prima dreams.

While surveying points for a roofing company, I witnessed the exploitation of this country’s resources and of our fellow man: a field of workers and vegetation alike sprayed by a low-flying aircraft in a mist of poison. I turned to my colleague in the field as if to say what Jayne Marek aptly writes in “Old Sedan (Revolutionary Letter 2020)”: “how do we enter the language of the raw, / what is thunder broken into 300 million pieces / where no one can take a full breath.”

It was in the light of an indifferent sun that I questioned whether I had understood di Prima’s influence on these anthologized poets. It was from a darkness of discernment when I began to map the message of di Prima’s work, of what the poet Timotha Doane writes: “extreme dark / Diane instructs me / bright flame melts the lotus into her.” I have begun to see things not only with my eyes but with the eyes of the poets who’ve gone before me. What I see will continue being more precious to me, as how other poets, like di Prima, experienced things. Indeed, there are featured poems having nothing to do with di Prima, but it will be her spirit, as the poet experiences it in their soul, which is the fundamental apex of this tribute of an anthology. Not giving you di Prima, but giving what di Prima does to you.

Conformity dominates the spirit of the present-day American. At times the words and acts of our more robust poets seem treasonable. Regardless, the anthology arrives at a peaceful acceptance between recognizing societal constraints and feeling free of them: “thou you have died / you teach me still,” and I wonder to what extent are we prepared to content ourselves to conform expectations of societal successes? When the reader understands these poets are putting a slanted appreciation on di Prima, sourced from their own subjective conflicts and interests, do we feel prepared? Di Prima has spent decades in pages showing us the strain of living in a world where we’re forced to conform to one way of revolution. Wisdom Body Collective presents us with equally adequate and alternate paths to choose.

What these poets have absolved from di Prima is the individual resistance that has broken through patterns of conformity. Mike Mosher’s “Dianaesque” asks us to realize that the “material thing / that you own diminishes your quality of life as much as it / enhances it.” In equal measure, the anthology equips us with vivid portraits of bodily awareness: “Uterus is a sensitive keeper of time,” and this is what I found so moving in the few di Prima letters I’ve read and what Wisdom Body Collective ostensibly upholds: “where hope lives outside / the lines.” The anthology is a conscientious falling into a legacy of revolutionary poetics.

Through its entire breadth and length, More Revolutionary Letters is powerful in meaning. Readers unfamiliar with Diane di Prima’s work will revel in the full import of her letters from half a century ago. To use those same letters as a poetic manifesto is what these featured poets’ lyricism may depend on. How much readers rely on di Prima’s letters to validate the anthology’s veracity of a tribute is of a similar matter: the less that figure, the more the revolution is realized. May it continue.

Nicholas Skaldetvind

Stockholm University