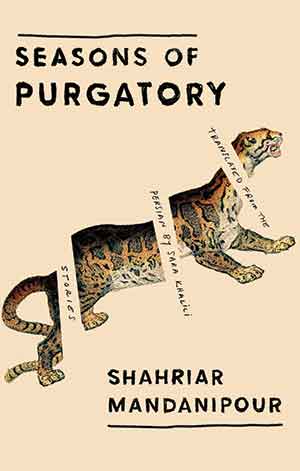

Seasons of Purgatory by Shahriar Mandanipour

New York. Bellevue Literary Press. 2022. 208 pages.

New York. Bellevue Literary Press. 2022. 208 pages.

THE NINE BLISTERING, sometimes fantastical short stories in exiled Iranian writer Shahriar Mandanipour’s first collection to appear in English, Seasons of Purgatory, underscore the wrenching aspects of war and its aftermath and often focus on immorality and mortality.

The opening story, “Shadows of the Cave,” first appeared in Persian in 1985 and was translated into English in 2018. It introduces a subject and theme that occurs in several of the stories: the parallel relationship between humans and animals. A widower, Mr. Farveneh, is an insomniac baker who spends a great deal of time observing a zoo from his apartment window. With “exceptional powers of depiction and analysis,” he sees man as a “pitiable two-dimensional creature with one half of his being inclined toward a societal life and the other half preferring the sanctuary of instinctive isolationism.” He asserts that nature is best “minus the beasts,” that “man became man when he withdrew from the animal kingdom.” With the achievement of “progress, prosperity, and self-sufficiency,” he proposes there is “no longer any need for the animal kingdom because “the vital resources that animals squander far outweigh what they can offer.”

In other stories, animals seem both real and symbolic. An entire family in “Mummy and Honey” is pursued through generations by the “glittering reflection” of an elusive viper in their sprawling, decrepit dynastic mansion overseen with patriarchal authoritarianism. Generations of fathers, sons, and wives infected with the venom of greed even hire a snake catcher to find the slithering serpent. A grieving father haunted by bloody memories of war in the painfully mournful “The Color of Midday Fire” is unable to revenge his young daughter’s death and kill the leopard who devoured her at a waterfall because his “child’s blood runs in its veins.”

Disturbing, gruesome details of another corpse dominate the powerful images of an Iraqi defector’s last days in the title story. Iranian troops tortured by a moral dilemma are suspended between indifference and common decency regarding how to dispose of the “dried-up skeleton” whose “skull shines” at a full moon. His “clothes decayed, the trichina grew gaunt on his flesh, the sun sapped his fat, and the earth around him turned slimy and black.” At one point, when the wounded soldier begged for water and a sympathetic Iranian threw a cask toward him, a captain blasted it with a machine gun, shouting, “’Don’t you know that you shouldn’t give water to a wounded man?’” Preservation and survival overwhelm and overshadow human nature.

Other deaths provoke vengeance and violence in “King of the Graveyard” and “Seven Captains.” The first, “Dedicated to Iran’s forbidden graves,” traces the futile task of parents seeking the burial site of their “unjustly accused” young son. The title character claims to know “every nitty-gritty detail” of the deceased residents, but it appears as though the whole excursion “seven steps to the right . . . nine steps to the left” may be a calculated swindle. In the second, an exile returns twenty-two years after his lover has been stoned to visit the location of her execution, hoping to discover what might have survived through the “sorrow of loneliness and isolation.”

These often brutal and bleak reminders of “commonplace memories of mundane relationships” result in a hauntingly nuanced and provocatively impressive collection.

Robert Allen Papinchak

Valley Village, California

When you buy a book using our Bookshop Affiliate links on this page, WLT receives a commission. Thank you for your support!