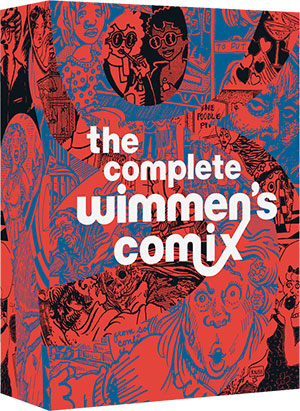

The Complete Wimmen’s Comix

Seattle. Fantagraphics Books. 2016. 728 pages.

Seattle. Fantagraphics Books. 2016. 728 pages.

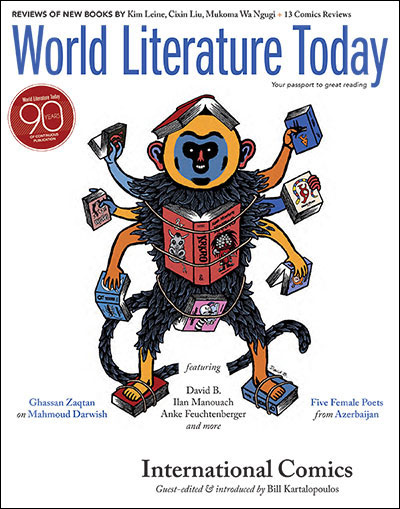

The social upheavals of the 1960s resulted in a variety of revolutions: in politics, the arts, and in the culture at large. Included among these was a major new direction in comics. To set themselves apart from the mainstream, and to signal a radical shift in vision, artists like R. Crumb, Harvey Kurtzman, Art Spiegelman, and others dubbed their work “comix” to indicate their X-rated, underground approach to the genre.

The majority of these first-wave comix artists were men, but in the early 1970s a vibrant group of women artists emerged, mainly on the West Coast, in the pages of Wimmen’s Comix. Their subjects, too, were often X-rated and included sex, drugs, relationships, women’s liberation, gay liberation, politics, and trenchant satire of American cultural institutions. The two volumes of The Complete Wimmen’s Comix provide a rich and complete overview of the development of the Berkeley-based publishing collective from a 1970 incubator issue of “It Ain’t Me Babe: Women’s Liberation,” which preceded the establishment of Wimmen’s Comix in 1972, through the seventeenth and final issue, in 1992.

The names of familiar artists appear on many of these pages. Included are Trina Robbins, a major force behind “It Ain’t Me Babe” and creator of the first lesbian comix, and Aline Kominsky (later Kominsky-Crumb, yes, that Crumb), whose Goldie comix are autobiographical and hilarious. Alison Bechdel and Lynda Barry make brief appearances, but their inimitable styles are apparent in these early comix and presage their later successes. Also outstanding are Lee Binswanger, whose minimalist comix are both elegant and incisive; Diane Noomin, whose “Rubberware” takeoff on a Tupperware party is perfect X-rated parody; and everything by Lee Marrs, who can satirize almost any cultural phenomenon.

With a rotating editorship and a mission to welcome new artists, the issues can be uneven in quality and drawing styles even while they give the reader a keen sense of the themes relevant to the historical moment, most especially women’s liberation. Starting with Issue 7, a theme is stated on the cover—from “Outlaws,” “Women at Work,” “International Fetish,” and “Disastrous Relationships” to the “Kvetch” issue—and the comix within loosely relate to the cover subject. No matter the theme, though, the comix within are liberated from any external or internal censorship—genitalia abound in these pages as do images of almost every imaginable kind of sexual encounter. Prudes were not invited to the women’s comix party, nor would they want to attend.

Despite the unevenness and the somewhat dated, if historically accurate themes, every issue has its gems, and those are the ones that stay with the reader. The work is often hilarious and occasionally quite moving, as in the combined work of Trina Robbins and Sharon Rudahl in Issue 10 (1985), where they illustrate “The Partisan Song,” by Hirsh Glik, identified as the “poet of the Warsaw Ghetto.” The Yiddish words of the song have English translations beneath, and the Holocaust-themed illustrations are heartbreaking. This is a bold move that underscores the breadth of vision represented in these pages and the remarkable talents of these artists. These volumes invite the casual browser as well as the aficionado to marvel at the talented spirit and energy of an earlier moment in the history of Wimmen as well as comix.

Rita D. Jacobs

New York City