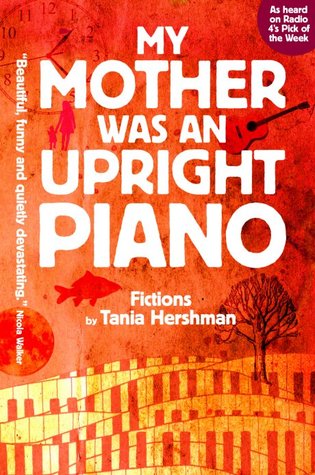

My Mother Was an Upright Piano by Tania Hershman

Bristol. Tangent. 2012. ISBN 9781906477608

My Mother Was an Upright Piano is Tania Hershman’s second collection of very short stories—her first, The White Road and Other Stories, was commended by the judges of the 2009 Orange Award for New Writers. Her presentation of the tragedy and the oddity of our human lives is the typed equivalent of a performance artist at MOMA: strange, unfamiliar, captivating.

My Mother Was an Upright Piano is Tania Hershman’s second collection of very short stories—her first, The White Road and Other Stories, was commended by the judges of the 2009 Orange Award for New Writers. Her presentation of the tragedy and the oddity of our human lives is the typed equivalent of a performance artist at MOMA: strange, unfamiliar, captivating.

The universe’s dark energy palpitates on Hershman’s pages; she gives emptiness form. Characters struggle to communicate, to make themselves known to others. Hopes for the world to be other than it is are met with silence. Longing blankets the text. Sentences stop before they reach their conclusion, words omitted by the author in sympathy with the reticence of her fictional creations. The unsaid contains both dagger and salve, and Hershman’s silences both break and heal the heart.

The beautiful story “Life Breaks Out” is a manifesto of Hershman’s sense of the tragic indifference of the world into which we are thrown. The story starts, “Life was small . . . Life curled up to make itself even smaller, to fit into the kinds of holes that insects crawl into to get away from bigger insects. Life was sad.” As Life grows, the significance of a mother and child boarding a small boat wanes. The story ends, “Life looked down and saw a tiny boat with tiny people. Life couldn’t remember being that small, let alone as miniscule as an insect. . . . Life blew a little on the tiny boat. Life watched as the tiny boat swayed and tilted, dipped and dove, sank and disappeared. Then Life turned around and got on with something else.”

Fresh imagery, such as the use of a formerly upright piano as a metaphor for a mother who falls under the spell of a maestro who is not her piano-tuning husband, awakens the mind from its habitual vantage point to see anew the universal truths it has learned to gloss over. Hershman shows us that our world is, in fact, a nearly unrecognizable place, and we are all aliens in it, alien in our skin, unknowable not only to each other but often to ourselves.

Everything is not illuminated in Hershman’s storytelling, and the reader may well ask himself at the end of a story, “What just happened?” The answer: something vague, absurd, the pain of our attempts at human relationships, and our tenuous place in the universe revealing themselves, and they are beautiful. [Editorial note: To read a story by Hershman, see page 18 of this issue.]

Kerri Shadid

Edmond, Oklahoma