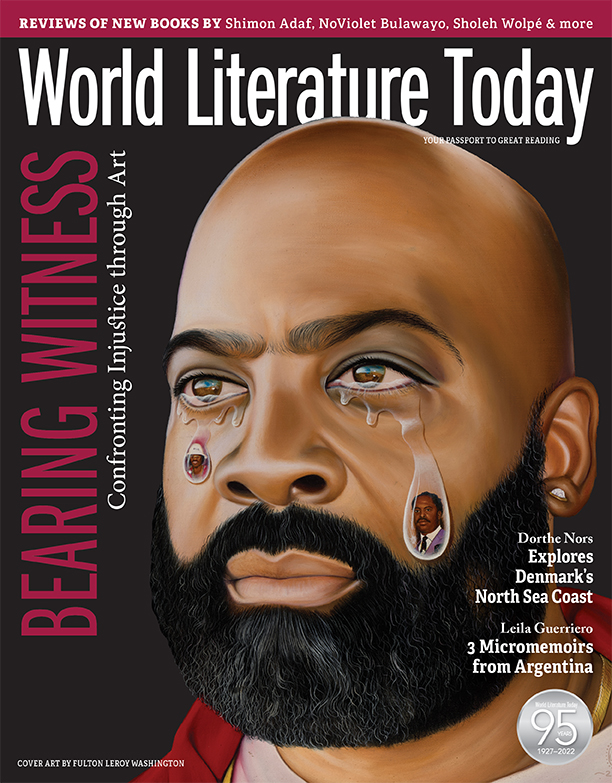

Surveying the Anthropocene: Environment and Photography Now

Edinburgh. Edinburgh University Press. 2022. 234 pages.

Edinburgh. Edinburgh University Press. 2022. 234 pages.

THIS VISUALLY STUNNING collection of photographs and essays presents readers with an unsettling view of the moment in time in which we find ourselves. As Robert Macfarlane explains, in one of the most powerful pieces in the book, although “the Earth epoch we at present officially inhabit” is the Holocene—which began around 11,700 years ago—such is the magnitude of change wrought by our species on the planet that the term Anthropocene is seen by many as a more accurate designation. It points to the way Homo sapiens has had a massive, and largely destructive, impact on Earth’s ecosystems. Given the threat we pose to other species, there are credible grounds for supposing that humans are responsible for causing the sixth mass extinction event. There remains some debate as to whether Anthropocene is the best term for the current period. Whatever we decide to call it, the key point, as Adam Nicolson puts it in the book’s final chapter, is that “this is one of the ages of loss.”

How do we live with that loss? How do we grieve for it? How can we relate to it? What can we do to prevent it from getting worse? How do we picture it and express it in words? Surveying the Anthropocene offers eloquent testimony from a range of perspectives that address these urgent questions.

Many of the photographs make a strong, immediate impression and stay in mind long after the page that holds them has been turned. Not all of them are shocking. Meryl McMaster’s On the Edge of This Immensity offers a primeval composition that has a haunting, almost numinous quality. Tim Flach’s image of a white-bellied pangolin clinging to its mother’s tail suggests a kind of otherworldly beauty and vulnerability. Patricia and Angus Macdonald’s aerial photo of a gannet colony conveys nature’s dazzling abundance. But the bulk of the images, however artfully executed and presented, contain an element of horror. This can take the form of the lethal cargo of multicolored plastic in the body of an albatross, the desolation of the area around Chernobyl, or scenes of the miseries caused by climate change.

Often, despite the ugliness of their subjects, the photographs are beautiful to look at. Daniel Beltrá’s Spill series, documenting the environmental disaster that followed the sinking of BP’s Deepwater Horizon oil platform in the Gulf of Mexico, and Timo Lieber’s THAW series, showing the melting of the Greenland ice cap, are attractive in terms of the shapes and colors the photographs capture, even though the reasons for these shapes and colors are horrendous. One of the difficulties the book identifies is what Owen Logan calls “the aestheticization of environmental destruction.” He warns of the way photographers can unwittingly end up merely contributing to “the spectacle.” There is sometimes a fine line between photographs that alert us to environmental damage and those that simply “feed a commerce of iconic images.”

Surveying the Anthropocene brings back to mind a comment of Susan Sontag’s in On Photography: “To suffer is one thing; another thing is living with the photographed images of suffering, which does not necessarily strengthen the conscience and the ability to be compassionate. It can also corrupt them.” Patricia Macdonald lays a striking assemblage of “images of suffering” before readers. Her book offers a cornucopia of pictures that vividly illustrate what Aldo Leopold described as “a world of wounds.” Will these images help to strengthen conscience, compassion, and action, or simply entertain readers with the easily flicked-through abundance of their photographic talent?

If the essays accompanying the images are read, it’s less likely that the kind of corruption Sontag warned of will take hold. These carefully chosen pieces provide contexts that frame the photographs in perspectives of informed and incisively expressed concern. Jared Diamond’s “Lessons from a Pandemic” flags the need for cultivating a sense of “world identity” so people can understand that many of the problems we now face can only be solved effectively by “a united global effort.” George Monbiot makes an impassioned case for recognizing the value of rewilding. Bill McKibben urges us to see that companies dealing in fossil fuels constitute “a rogue industry.” Adam Nicolson calls for us to enter “the age of empathy, both within our own species and between it and the rest of the world.” The words of these and the book’s other essayists help readers see beyond the surface of what the photographs present so eye-catchingly.

For me, one of the most memorable photos in the book features an ice stupa in Ladakh. Named after Buddhist stupas—hemispherical mounds usually containing relics—ice stupas are essentially artificial glaciers created to store water. Photographer Greg White explains the conditions that led to their construction: “The area receives little rain, so people rely on melting glaciers to obtain water for irrigation and livestock. But climate change has caused the glaciers to shrink and the flow of their meltwater to become erratic.” The solution found for this problem is elegantly simple. In late summer, local people collect glacial meltwater. This is sprayed at night onto a domed structure made of branches, which freezes. Then, says White:

The ice stupa starts to melt in March and will continue to do so until around July, when rainfall is at its lowest. The conical shape shields much of the ice from the sun. This means the tower, which can reach 50 metres in height, melts slowly, feeding surrounding streams. The following summer the cycle repeats.

In this important book, Patricia Macdonald has constructed a kind of literary stupa that holds a rich reservoir of words and images. Hopefully the meltwater released by reading it will help inform and sustain the sense of environmental concern that is so urgently needed if we are to find our way through the Anthropocene deserts we have created.

Chris Arthur

St Andrews, Scotland

When you buy a book using our Bookshop Affiliate links on this page, WLT receives a commission. Thank you for your support!