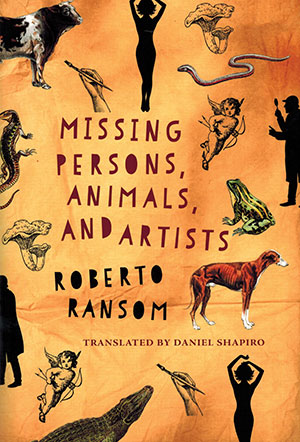

Missing Persons, Animals, and Artists by Roberto Ransom

Chicago. Swan Isle Press. 2018. 177 pages.

Chicago. Swan Isle Press. 2018. 177 pages.

Roberto Ransom’s openings are not just that. The first story in Missing Persons is about a pet lizard grown big enough to devour its adoptive family. Ransom’s ingenuity lies in drawing out this topic’s surprising means of presenting caregiving and loss. The first story’s unexpected developments parallel its relation to the other stories. Who could foresee a series of nuanced and unsettling tales about memory, art, betrayal, and divinity from a volume that begins with a housebound Godzilla? Perhaps someone who pays close attention to first sentences, or who reads things at least twice, because—and it took me a while to notice—Ransom employs anaphora especially well. “Lizard à la Heart” begins, “The bathroom hasn’t been open for days. Under the door, as always, it smells like a swamp.” Though syntactically nothing is missing, the words “for days” and “always” map out mysterious antecedents and seductive postcedents for the unsuspecting reader.

What happened? What’s next? This is an appetizer for the initial sentences of later stories, all in Daniel Shapiro’s superb translation from Ransom’s original Desaparecidos, animales y artistas (1999). The beautiful elaboration of the capricious time of artistic labor that characterizes “Three Figures and a Dog” begins, “He liked to be in the chapel at dawn and also in the afternoon when something similar, though not identical, occurred. For that to happen, he had to leave home when his wife got up to milk the cow.” “Something similar” and “that” are more syntactic anaphora than those that open “Lizard” because they leave their possible referents reliant upon (a still unknown) context. One protagonist of “Three Figures” is a medieval Italian painter. Another is a contemporary art historian who tries to restore old paintings whose figures and colors are barely visible beneath the tracks of time. In this story, Ransom transposes anaphora to the whole text, structurally and thematically. The postcedent of the first protagonist’s story, which involves inspiration’s fickleness and a strange dog, becomes the antecedent of the art historian’s work. The story’s characters form a temporal trinity, two moments spanning the ages and the reader’s encounter with them. The triangle’s center nurtures the potential Ransom grounds as skillfully as he liberates, intriguing and delighting his fortunate readers.

Ransom’s stories set free at least as many wonders as they define.

Ryan Long

University of Maryland