Name Me a Word: Indian Writers Reflect on Writing

New Haven, Connecticut. Yale University Press. 2018. 410 pages.

New Haven, Connecticut. Yale University Press. 2018. 410 pages.

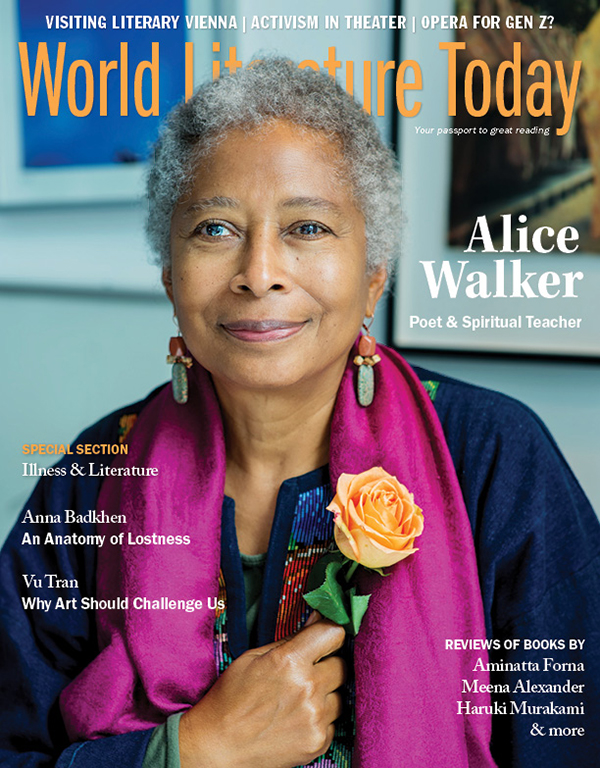

The poet and critic Meena Alexander begins her introduction to the anthology Name Me a Word with a personal anecdote about her encounter with the novelist Raja Rao. Rao spoke about the “invented English” he had gradually perfected with practice. The word “invented” provides a key entry point into the major concerns of this timely anthology of more than a century of major Indian writers reflecting on writing.

Alexander deftly sidesteps the worn-out clichés that permeate discussions of the “alienness” of English versus the “authenticity” of Indian languages. Indeed, invention in the face of a multiplicity of languages characterizes both anglophone Indian writing and works in other Indian languages. As Alexander writes, “The porous slipping borders of multiple languages that Indian writers inherit is often in evidence, if not overtly in the work, whatever the language of its composition, then in its dream life, the undertow that takes hold of the reader and tugs her in.” These porous, slipping borders of literature’s “dream life” are evident not only in the self-conscious attempts at linguistic invention in anglophone writers like Rao or Rushdie but also in the writings of Bengali poets like Jibanananda Das.

I mention Das especially because his poem “Name Me a Word” provides Alexander with a resonant title for her anthology. According to Alexander, Das searches for a word that even as it evokes the vastness of the sky, possesses the delicate power of touch that only love can bring—a woman’s hand capable of cleansing “the dirty innards of history.” The poem that dwells on what it means to name ends with the evocation of a supernal thirst that birds possess—and by extension the maker of words and all who seek the mortal power of language. His poem seems the perfect invocation of this gathering of voices . . . a veritable river of words into which many languages flow.

The purpose of this anthology is thus not only to showcase the vibrancy and multiplicity of this gathering of voices but to also explore how literary writers probe the “dirty innards of history.” It would be worthwhile to close this review, then, with the Bengali poet Nabaneeta Dev Sen’s “Combustion” as it conjoins linguistic invention with a politicized exploration of the dirty innards of history: “As powerful / As the volcano range / Is this range of alphabets / Touch it / And you’ll burn to ashes / Instantly.”

Amit R. Baishya

University of Oklahoma