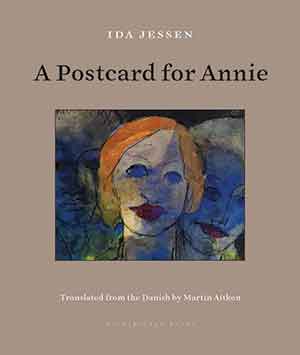

A Postcard for Annie by Ida Jessen

Brooklyn. Archipelago Books. 180 pages.

Brooklyn. Archipelago Books. 180 pages.

IT’S HARD NOT to become hooked by Ida Jessen’s stubbornness; her refusal to tidy things up for us. This sixty-year-old Danish author harbors no illusions about women’s troubled relationships with men; nor does she hold out hope for the much-talked-about benefits of female self-discovery and empowerment. She knows women have no clue as to what pushes them into failing relationships and even less insight as to why they remain. In her wonderful new collection of stories, A Postcard for Annie, we hear the collective howl of women falling hard upon the ravages of middle age, which has exacerbated their bitterness, grief, and loneliness.

In an earlier stellar work, “A Change of Time,” a woman visits her dying husband in the hospital only to find he is always sleeping when she arrives. The nurse fills her in, but she can’t help thinking something is amiss. She will soon be a widow at fifty, and although her marriage has been one without laughter or intimacy, she fears for the future. He is the town’s physician, and for reasons that remain mysterious to her, he always took umbrage with her inability to come up with a quick retort in conversation. “Human kindness is my nourishment and my fatigue,” she thinks. “Why is it not sufficient? I have more than most.” The book is set in a form of diary entries where, even in this personal space, she remains restrained. Jessen doesn’t allow her to condemn her husband outright. Instead, she circles her sadness, always considering that perhaps there is something she doesn’t see. This insecurity is present in most of Jessen’s characterizations.

In one of the captivating stories in her new collection, a woman named Tine is frustrated by her husband who is refusing all her advances: “Beautiful underwear, she’s tried that. She’s tried beautiful. She’s tried intelligent, good, and loving. She’s tried funny, naughty, and wild.” But nothing has worked. She retreats to her son’s room and thinks how long it has been since he left home; but her thoughts wander back to her husband. Jessen often seems to consider children as nothing more than an afterthought, transitory beings that are no longer essential. She keeps rethinking about how they first fell in love and how overwhelming it felt: “Once, they existed. Love existed, hope existed, and faith existed. As if, suspended in that bashful and benign state of being, they each knew they were lovingly anticipated.” But now there was a void where wonderment once was. Jessen knows better than to have her characters perform autopsies on their dying love affairs; she knows the pointlessness of such endeavors.

In another tale, “An Excursion,” Tove is a successful businesswoman who reupholsters furniture and sells material for curtains. On a random day at an antique fair, she finds herself captured by a yellow floor vase whose color was precisely the shade of yellow that had always overwhelmed her: “Even now, in the home she had made as an adult, she possessed very little that was yellow, as if she were afraid of overdosing, just as she would rarely go to the doctor, fearing herself at bottom to be a hypochondriac.” Behind her, a man was staring at her looking at the vase, and soon enough they were intricately caught up in each other’s lives. She learned to cook to please him and liked when he called her “honey.” But soon enough things shifted and she heard that when she spoke to him her voice was timid, her laughter more restrained. But she couldn’t address the thought of leaving him, because she knew that “without him she was shapeless.”

Ida Jessen is a master chronicler of the messiness that overtakes the female mind. She writes unburdened by polemics of any kind. Her characters are vividly drawn—sometimes eccentric, and at other times ordinary—but they seem strangely authentic to us. We see ourselves in almost all of them. Jessen never wanders into alien territory. She is not interested in whether something is fair or not or pleasing to all parties. Her characters tend to be women of a certain age—not yet elderly but old enough to see that their unfulfilled desires will continue to be their lifelong companions. Only occasionally does she permit some of her women characters to relish for a bit, thinking back to their early years when they were filled with a life force that felt overpowering. But that was long ago, and most of those memories have become stale, almost mocking all that has followed.

Elaine Margolin

Merrick, New York

When you buy a book using our Bookshop Affiliate link, WLT receives a commission. Thank you for your support!