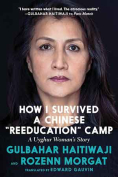

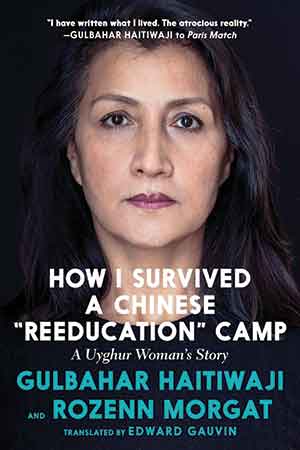

How I Survived a Chinese “Reeducation” Camp by Gulbahar Haitiwaji & Rozenn Morgat

New York. Seven Stories Press. 2022. 235 pages.

New York. Seven Stories Press. 2022. 235 pages.

AS TOLD TO journalist Rozenn Morgat by Gulbahar Haitiwaji, and beautifully translated by Edward Gauvin, this is a current and deeply disturbing personal account of being targeted as a Muslim Uyghur immigrant to France, lured back to China, and incarcerated for three years in government prison and “reeducation camps.” Early in her incarceration, Gulbahar, which means “spring flower,” says to herself, “In my secret garden, amid my memories, I’d dug up a little square of dirt. There I planted the seeds of my resistance.” This memoir puts a much-needed face on abstract world news about the upwards of one million men and women estimated to have been taken from their families and jobs, imprisoned in camps, and “reeducated” in western China.

A story of individual survival—of starvation, brainwashing, forced sterilization, and other abuses told and untold—the narrative traces in stark relief the massive effort through which the Chinese government seeks to erase the cultural ties of ethnic and religious minorities—especially Muslims—perceived as detracting from unified national goals of economic expansion and political influence across Asia and Europe. But Gulbahar’s story also illuminates the terrifying hold the government seeks over Uyghur voices outside the country, to control global narratives as well as the domestic one. Though she had had no previous political interest or involvement herself, Gulbahar’s daughter and husband had protested Chinese government treatment of Uyghurs on social media. Gulbahar was explicitly held hostage to manage her family’s and the expatriate community’s voices. Gulbahar’s family, both in France and in China, were all, in turn, also effectively held hostage, muzzled in fear for Gulbahar’s and their own safety. Her family in France stopped speaking about her on social media.

With one million incarcerated, often on such vague charges as “praying,” millions more family members, inside and outside China, might be controlled. When Gulbahar was finally allowed to return home to France, she found freedom “bitter.” She had had to make false statements to secure her own release. Friends in the Uyghur-French community now met her with caution, whispering that she must be a collaborator and her home “bugged.” Her survival was not without great cost; she felt China had won.

With the exception of the preface and a brief afterword written by Rozenn Morgat, this co-authored book is presented in Gulbahars’s voice; her clear-eyed witness and detailed memories power this tale. At times, particularly when her very personal account shifts into detailed political context or historical background, I was pulled off-center, unsure if the “research information voice” was the journalist’s or Gulbahar’s. A narrative structure better distinguishing these different elements might have clarified the authorial voice(s).

The woman pictured on the front of this book debated right up to publication whether to use her own face and name. After reading this—almost in one sitting—I understood why. On her final flight home to reunite with her family, Gulbahar thinks, “part of my soul, too, was still wandering in the frigid hallways of Baijiantan, sitting in the courtroom where the policeman who judged me was, no doubt, passing judgment on other innocent people. . . . The madness sweeping our planet had forever torn me from the peaceful life I’d once lived.” Gulbahar’s is a brave and important voice; her choice to lay her name and face bare to speak as loudly as possible calls us, in turn, to witness, to amplify, to not look away.

Alison Mandaville

California State University, Fresno

When you buy a book using our Bookshop Affiliate link, WLT receives a commission. Thank you for your support!