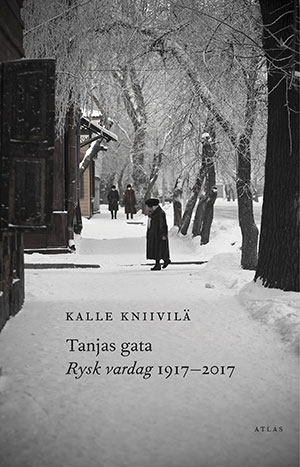

Tanjas gata: Rysk vardag 1917–2017 by Kalle Kniivilä

Stockholm. Atlas. 2017. 279 pages.

Stockholm. Atlas. 2017. 279 pages.

Tanjas gata: Rysk vardag 1917–2017 (Tanya’s street: Everyday life in Russia, 1917–2017) is the fourth volume in a quartet of books about contemporary Russia and its roots in the Soviet Union. In all of them, the analysis is illuminated by records of interviews with ordinary Russians and of their writing. Tanjas gata is set apart by its greater historical reach—in it, Kalle Kniivilä attempts an overview of an entire century of complex and violent change. In a characteristic move, he frames his narrative within a modest street in St. Petersburg: “Tanya’s street is barely 1,500 meters long yet encompasses the history of both the Soviet Union and post-Soviet Russia. The extraordinary fates of ordinary people over the past century.”

Tanya Savityeva’s family ran a bakery in the street until the Wehrmacht encircled the city in 1941 and kept it under siege for two and a half years. Most of them had starved to death when Tanya wrote in her diary: “Mother, on 13 May in the morning 1942. The Savityevs are dead. All have died. Only Tanya is left.” Two years later, starvation had killed her, too, at the age of fourteen. The stories of the Savityevs and their neighbors are told in a sequence of chapters, each devoted to a decade between 1917, the year of the revolution, and 2017, a year when the great leader of Russia is (still) a boy from Tanya’s street—Vladimir Putin. Only one chapter is allowed to break the orderly sequence: “1942. The Siege.”

Despite the terrible years of World War II as well as the recurring periods of deprivation and fear of street and state violence, the narrative testifies above all to people’s instinct for survival, resilience, and capacity for kindness under stress. We follow their lives with real concern, but they also, somehow, help demystify Russia and make the eccentricities of its history a little easier to grasp. What, for instance, of the Russian willingness to put up with despotic rulers? The head of a St. Petersburg hospital shares a very common view: “Call him what you will—president, prime minister, king, great leader—it doesn’t matter. Always, there must be someone who says: ‘Put the burden on my shoulders, I can cope.’ A father-figure who says: ‘Children, don’t worry, daddy will deal with it, everything will be fine.’”

In Tanjas gata, Kalle Kniivilä uses his almost ethnographic approach to create a sense of historical continuity with the present that has featured in his earlier books. After Putin’s people: Russia’s silent majority (Atlas, 2014), two studies of geopolitical flashpoints followed—first in Crimea Is Ours: The Empire Returns (Atlas, 2015) and then in Children of the Empire: Russian Life in the Baltic (Atlas, 2016). All are not only readable and well informed but also uniquely gripping thanks to the kaleidoscopic range of views the author has recorded in the countries he knows so well.

Anna Paterson

House of Glack, UK