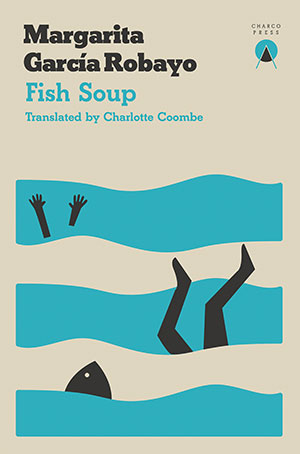

Fish Soup by Margarita García Robayo

Edinburgh. Charco Press. 2018. 226 pages.

Edinburgh. Charco Press. 2018. 226 pages.

Having garnered the praise of Juan Cárdenas and Juan Villoro, young Colombian author Margarita García Robayo is being published for the first time in English in a three-part volume entitled Fish Soup. The text includes the novellas Waiting for a Hurricane (Hasta que pase un huracán, 2012) and Sexual Education (previously unpublished) as well as a collection of short stories entitled Worse Things (Cosas peores, 2014).

An unnamed, college-aged female in search of middle-class comforts is the narrator for the volume’s opening piece, Waiting for a Hurricane. The novella is set in a Caribbean city in Colombia characterized by rainy days, hazy thoughts, and sensuality, where the narrator continually meditates on the easiest means to get ahead or, at least, get out. The narrator—growing up with “useless” parents whose days are occupied with unfulfilling tasks, living in a city whose leaders consistently fail to build proper infrastructure, and uncertain as to how to forge healthy relationships—typically approaches setbacks with laconic escapism: “When people asked me, what do you want to be when you grow up? I’d reply: a foreigner.”

Friends and lovers come and go, and the narrator decides she isn’t suited for formal education; the only constants in her everyday life are the rain and a nebulous hunger for something different—the feeling that life will pass her by if she fails to flee. The narrator abandons her studies and begins spending her aimless days with on-again, off-again boyfriends, both hoping for and fearing something that will shake up her unexceptional existence. As she pithily tells a boyfriend: “We’ll always be here, waiting for a hurricane to come.”

The narrator eventually resorts to bolder measures and finds work as a flight attendant; during frequent flights to Miami—a veritable Shangri-La for the Latin American jet set—she unsuccessfully attempts to trick a pilot into impregnating her. The novella concludes with the narrator back in Colombia, very little if anything having been resolved.

Both Worse Things and Sexual Education explore similar themes and strike a similar tone. García Robayo’s stories are filled with dysfunctional families at dead ends; the nagging sense of middle-class young adults living protracted childhoods; idiotic contests of sibling one-upmanship; sordid hookups that leave lovers feeling unfulfilled; hypocritical sexual mores that only serve to twist people’s lives into knots. García Robayo’s narratives read like vignettes, ending in ambiguous but enjoyable ways that task us to ponder a single, constant enigma: How can characters get unstuck from their quotidian paralysis?

Charlotte Coombe proves herself an apt translator; like the author, she keenly avoids apostrophizing and thus preserves the brusque, even immodest crispness of characters’ dialogue. All told, García Robayo’s stories are as satisfying and certainly as pungent as the most potent of fish soups.

Kevin M. Anzzolin

University of Wisconsin–Stout