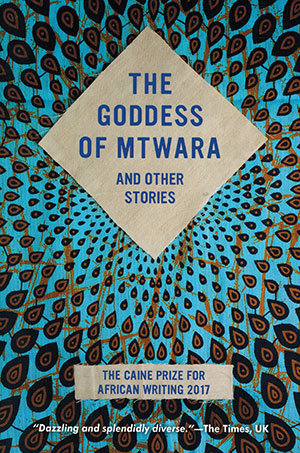

The Goddess of Mtwara and Other Stories

Northampton, Massachusetts. Interlink. 2017. 271 pages.

Northampton, Massachusetts. Interlink. 2017. 271 pages.

Populated by a pantheon of established and emerging African literary figures, The Goddess of Mtwara and Other Stories boasts an array of fantastical and contemplative short tales. Front-loaded with the 2017 Caine Prize shortlist and rounded out by selections from the prize’s Tanzania workshop, the anthology consolidates the fantastic and the contemplative, yielding a medley of stories palatable for the broadest tastes.

Desire and self-preservation pervade many of the assembled works, demonstrating the flexibility of theme regardless of genre. Chikodili Emelumadu’s “Bush Baby” strikes a particular chord, melding an ancient and horrifying legend with the abrupt deterioration of a family, illustrating physical decay and delusion to a haunting effect. Emelumadu modernizes myth in a way analogous to contemporary horror cinema without relying on superficial fear to preserve a sense of uncontrollable loss.

The anthology’s magical entries are transient, however, as the collection opts for a more grounded and natural discourse, notably with Arinze Ifeakandu’s “God’s Children Are Little Broken Things.” Adopting a second-person perspective, the writer elaborates a journey of self-actualization through Lota, a young Nigerian student uncovering his repressed sexuality. The work exhibits shades of Barry Jenkins’s Moonlight, compelling one to experience beauty through discomfort and turmoil. Ifeakandu’s narrative vehicle grows more personal with each passage, bridging cultural gaps while remaining distinct.

Magogodi Makhene’s “The Virus” wields local color in a way unparalleled throughout the rest of Goddess. A lament on the disruptive and somewhat ineffable nature of cyberattacks, Makhene’s unique discourse accents the irony of hordes of American “cyvivors” seeking refuge in Africa from an electronic menace. The short story details the absurdity of the twenty-first century as technology hurls first-world society into a second dark age. The narrator’s musings are far more than criticism, however, as an ultimately tragic desire for a long-gone simplicity pours through each passage.

The collection is noticeably weighted in its front end, somewhat compromising the resonance of its latter half. Though it does not nullify outright the workshop’s standouts, including Esther Karin Mngodo’s titular piece and Abdul Adan’s aforementioned work, the thematic diversity of the shortlist partitions the anthology in a jarring fashion.

Despite any structural disjunction, The Goddess of Mtwara succeeds in illuminating the continent’s rising talent. No two entries feel redundant, though common thematic threads serve as a welcoming introduction to anyone unfamiliar with African literature.

Daniel Bokemper

Oklahoma City