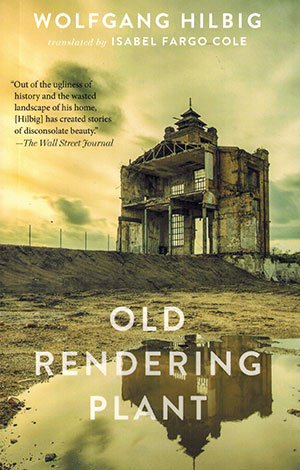

Old Rendering Plant by Wolfgang Hilbig

San Francisco. Two Lines Press. 2017. 108 pages.

San Francisco. Two Lines Press. 2017. 108 pages.

The setting of Old Rendering Plant is the German Democratic Republic in which Wolfgang Hilbig grew up. In a veritable perversion of the conventional German Entwicklungsroman model, Hilbig has his first-person narrator envision his “apotheosis” in a job at the rendering plant, which turns dead and dying animals into soap.

The narrator seems ineluctably drawn to the plant when, with graduation looming and absolutely no prospects for higher education, he must seek work. A job at the plant will satisfy his “strange interest in bad places” in which things harmonize with him, as he puts it. We see him, from childhood on, exploring slimy and malodorous places in a hideous has-been industrial landscape, which seems to be all that his whole village and its environs consist of. He is told not to go into these ruins because, in addition to their obvious structural dangers, it is rumored that they may also be hiding some of the many people who have “disappeared.”

The plant itself sits on an abandoned mine whose shafts wend in every direction underneath this moribund landscape. Now that the last tons of coal “had been transported away as reparations, bartered down the ramps of world history,” these shafts have room to spare for the bodies of those whom the succeeding state bureaucrats have displaced. It might strike us as ironic that the mine was called “Germania II”—even more that the rendering plant has been named after it.

While working at the plant does give its employees a bad reputation—literally leaving one with a bad odor that could not be washed away, despite the soap the plant rendered—the above-average wages offset that. The plant’s workforce includes the low-level and quasi-staff of the state security service, whose bosses strove to achieve a society sufficiently “dead” to offer absolutely no distractions for anyone.

All this is narrated in highly lyrical prose—until it tips over into a volatile rant defaming the “People’s Economy” and the bosses who thrive on the country’s cadaverous soil, just like the willows that flourish on the rendering plant’s waste. The narrator, having invited them for a beer at the local pub, purposely lets loose with this rant before those state quasi-staff, and he revels in the “malicious glee” their faces reflect, glad to hear things they could never say.

Until this sharp disruption, the narrator’s progress has been a perfect illustration of the insidious way this regime had of co-opting individuals by totally immersing them in toxins both environmental and social. Is it any wonder that such a regime was happy to grant this author permission to leave for the West? Who could portray it as morbidly? It is a short book but a tour de force nonetheless, and Isabel Fargo Cole has succeeded admirably in giving it to us in trenchantly morbid English.

Ulf Zimmermann

Kennesaw State University