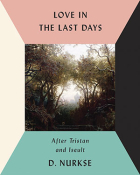

Love in the Last Days: After Tristan and Iseult by D. Nurkse

New York. Alfred A. Knopf. 2017. 90 pages.

New York. Alfred A. Knopf. 2017. 90 pages.

An acclaimed poet fond of mixing childhood and ecology, myths and quantum science, D. Nurkse publishes here his eleventh volume of poetry. Resonating with subtlety and texture, Love in the Last Days makes imagination queen, mediator, and silencer. Poet laureate of Brooklyn from 1996 to 2001, enjoying the fullness of his professional career, firmly established in New York, Nurkse is one of America’s most cosmopolitan poets. In Love in the Last Days, he artfully weaves his life’s journey into his work—his Baltic (Estonian) affinity with the primeval, healing power of woods and trees; his postmemories of exile; and his commitment to peace, justice, and human rights.

Nurkse dusts off the medieval tale of Tristan and Iseult and reshapes it into a postmodern myth. The story is told through a variety of narrative techniques (renga, dramatic monologue, ballad), a trilogy of spaces (evoked locations, mythic woods, and sea settings), as well as playful typographical effects close to concrete poetry, the most dramatic of which is the poem “The Grail,” in which the blank shape of a chalice in the center of the page is “protected” by the repeated word “Morois.”

From the tale’s medieval texts Nurkse gathered a rich harvest of terms whose evocative, quasimagical powers mingle with modern words and syntax. By turns lyrical and crude, noble and prosaic, even vulgar, this baroque language sets off illuminating details while reconceptualizing reality. The story of the love potion, particularly representative of this shock therapy, is handled in the first two poems, “The Philtre” and “The Hold.” Tristan and Iseult’s initial love-making charts a future full of sound and fury. It is both cautionary tale and road map for survival through the “obscure light” described by St. John of the Cross or Aleksander Wat. The lovers know that their passion will include destitution, exile, ugliness, and aging, and above all alienation from others and each other.

Acknowledging the palimpsestic nature of the myth’s many versions allows Nurkse to fuse medieval magic with post-Freudian subversiveness. The new myth emerges from the collective tales told by all the drama’s characters, including animals, trees, and the living spring. Nurkse stresses love as illusion, a reference to medievalist historian Marc Bloch, love as transgression of masculinity, patriarchy, power, and even death, and wilderness as escape into a mysterious, untamed part of the mind. There is no definitive romance here, no absolute happy ending, merely an attempt to control destiny’s damage in the urgency of the “Last Days.”

Alice-Catherine Carls

University of Tennessee at Martin