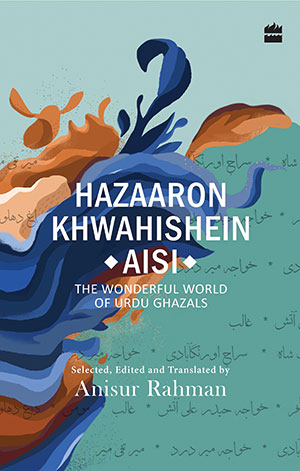

Hazaaron Khwahishein Aisi: The Wonderful World of Urdu Ghazals

New Delhi. HarperCollins India. 2019. 456 pages.

New Delhi. HarperCollins India. 2019. 456 pages.

Anisur Rahman, a former professor of English at Jamia Milia University in New Delhi, is a widely published scholar in the field of New Literatures in English. A poet as well (Earthenware: Sixty Poems, 2018), he is a gifted translator of Urdu poetry into English and vice versa. His bilingual Fire and the Rose: An Anthology of Modern Urdu Poetry (1995) was the first comprehensive volume on this subject and received praise for its succinct, instructive introduction, judicious selection of poets, and the poetic quality and accuracy of the translations (WLT, Winter 1997, 233).

Scholars generally agree that most of Urdu poetry breaks down into two major categories: the traditional Urdu ghazal and the modern Urdu nazm or poem. Since 1995, Rahman has turned his attention to producing, among other things, the first comprehensive bilingual anthologies of translations of both of these forms. Hazaaron Khwahishein Aisi: The Wonderful World of Urdu Ghazals is the first of these. The one on the nazm is slated to appear in 2020.

The ghazal genre originated in Arabic literature in the seventh century and then spread to Persian, Turkish, Urdu, and other literary traditions in the Islamic world. Its theme is most often love in its many variations, but also pro- and antireligious expression, left and right political attitudes, high- and low-brow social commentary, trenchant satire, and both wry and laugh-out-loud humor. Many of these themes appear varyingly in these translations.

The first three words of this book’s title are in Urdu, taken from a couplet by its foremost classical poet, Mirza Ghalib (1797–1869), quoted here, with the translator’s rendering: “Hazaaron khwahishein aisi ke har khwahish pe dam nikle / Bahut nikle mere armaan lekin phir bhi kam nikle” (Desires in the thousands I had, for each I would die / With many I had luck, for many I would sigh).

An apt description of the human condition to which everyone can relate.

The ghazal itself consists of a number of couplets, at least four but usually six or eight, each a kind of minipoem unto itself. It does not necessarily have to relate in theme or topic to other couplets in the poem, though they may. However, the best ghazals possess an overall mood or coloring, which adds to their sense of unity. Often seeming scattered to the uninitiated, the ghazal is held together as well by the poem’s metric pattern and by not one but two required rhymes. The second line of all couplets must end with the same word or words; this is the radif. The radif is preceded by the qafiya, which forms a separate, internal rhyme set. Rahman has been able to reproduce both sets of rhymes in a generous number of these translations. Here is an example from a longer ghazal by Bahadur Shah Zafar (1775–1862). The “assembly” in the first couplet refers to someone’s (the beloved’s?) salon or social event. The radif is in bold-italics; the qafiya in boldface:

It was never so very hard to speak,

but now

Your assembly was never so bleak,

but now

Who robbed you of your patience, my

poor heart?

Never so restless and ever so meek,

but now

What magic in her glance, I never

knew!

I would so much crave for and seek,

but now

So hard this time to bear the pangs

of love

My goal was never so oblique, but

now . . .

This collection contains 130 poems, two each by sixty-five Indian and Pakistani poets (five of them women), each introduced with a brief biographical note. The poems are drawn from six different literary periods from the seventeenth to the twenty-first centuries.

The volume’s concise and informative introduction to the ghazal, its history, and its place in the worldview of Urdu readers includes an illuminating discussion of ghazals written in English by contemporary poets: Americans Adrienne Rich and Robert Bly, Canadians Jim Harrison and Phyllis Webb, and Australian Judith Wright. Some readers might question the appropriateness of Rahman’s repeated, deliberate use of the loaded, fraught word “Oriental” in various contexts. In the translator’s note at the end of the book, Rahman discusses his theory of translation in general and of the ghazal in particular. Translating ghazals is not easy, but he has done so with skill, inspiration, and grace. The results for the adventurous reader are informative, gratifying, and entertaining.

Carlo Coppola

University of California, Los Angeles