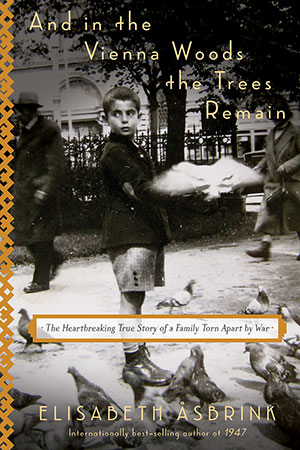

And in the Vienna Woods the Trees Remain: The Heart-breaking True Story of a Family Torn Apart by War by Elisabeth Åsbrink

New York. Other Press. 2020. 421 pages.

New York. Other Press. 2020. 421 pages.

A lifetime—seventy-five years—has passed since the liberation of Auschwitz-Birkenau, Bergen-Belsen, and other hellholes emblematic of the European extermination of perceived Otherness. Lest we forget, we need books like And in the Vienna Woods the Trees Remain: a slow-burning, relentless investigation of the persecution of the Jews and, at the same time, a compassionate study of an exiled child and family bonds stretched to breaking point.

Elisabeth Åsbrink is a brilliant journalist with a personal stake in exposing dark periods in contemporary history. The core narrative in 1947, her wonderfully readable “biography of a year,” is the post–World War II struggle of Europe’s surviving Jewry to find a refuge in Israel; the historical account is illuminated by the story of her father, a Jewish-Hungarian boy whose family is gradually eliminated.

And in the Vienna Woods is an earlier work, and the child adrift is another Jewish boy, Otto Ullmann. Otto’s parents loved him, their only child, so well that they sent the thirteen-year-old away from Vienna within a year of Nazi Germany’s annexation of Austria in 1938. Just a few months later, it had become clear that Jews would be brutally punished for existing at all.

Initially, Jewish Austrians were encouraged to leave the country, but they encountered endless problems with passports, visas, and finance. The Swedish Church mission was prepared to accept children like Otto only on the understanding that they would also be rescued from Judaism and saved for Christ. Otto never rejected his heritage but adapted—“reeds that bend in the wind don’t break” is a Jewish saying—and, as an adult, rarely mentioned his past. He would never see his Viennese family again, but their letters kept coming until the bitter end in 1944, when his parents died in the Theresienstadt concentration camp. The family letters (Otto’s replies are lost), infinitely sad testimonials of lost love, form a red thread running through the narrative.

Åsbrink grew deeply involved in documenting the lives reflected in the letters, but her investigative skills focus above all on the phenomenon of anti-Semitism, especially in Sweden and Austria. Traditionally beholden to the Germans, Swedes tended to approve of the Nazis; many marched and some preached odious rubbish about nation and race. In Austria, the irrational viciousness that characterizes all racism flourished like a social cancer. Mean restrictions of individual freedoms—like taking a walk in a park—ended with people growing to accept that their fellow citizens were herded into deportation trains.

It is the careful dissection of the pathology of persecution that makes And in the Vienna Woods such essential reading.

Anna Paterson

Aberdeenshire, United Kingdom