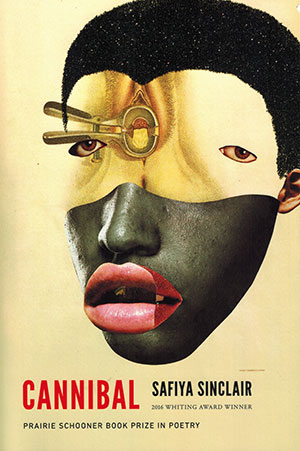

Cannibal by Safiya Sinclair

Lincoln. University of Nebraska Press. 2016. 111 pages.

Lincoln. University of Nebraska Press. 2016. 111 pages.

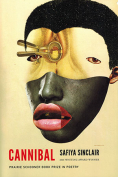

From shards of a “hand-me-down life,” “sufficiently tragic,” Safiya Sinclair conjures poetic magic, casting a spell whereby “cannibal masters the colonial / curse.” Weaponizing Columbus’s “canibal,” misconstrued sign for the savage indigene, immortalized in Shakespeare’s anagrammatic Caliban, Sinclair wields the Monstrous (imaged on the book cover) to bare the pride, hypocrisy, and fear that underlie colonial systems of control, especially racism and patriarchy, Prospero their icon. Awarded the Whiting and Prairie Schooner prizes, Sinclair’s debut collection, “carved in our own language of the macabre,” burns with pain and fury. Merging rage and rigor, the fierce voices of her black female personae embody emancipation and revenge.

African-rooted, Rasta-raised, a black island girl among white Americans, Sinclair foregrounds exile within her first four sections: at home; in America; in body; and in language. Most crucially, her personae share exile from “the lost chaos of history,” its “ghost arm” still “throttling” them. Their poems seek to claim a voice and a place in the human record.

Through epigraph, allusion, and quotation, Sinclair critiques colonialism and its texts—e.g., The Tempest, Jefferson’s “Notes on the State of Virginia,” Samuel George Morton’s pseudoscientific treatise on the relative intelligence of the races—and links herself to liberationist writers, including Rimbaud, Ginsberg, O’Hara, Du Bois, Baldwin, Lorde, Brathwaite, and Césaire. Thus, for example, an epigraph from Ginsberg—“America is this correct?”—underscores the irony of “America the Beautiful,” where “every night . . . my brother is a criminal.”

Cannibal pulsates with the lushness of Jamaica, its flora, fauna, rhythms, sea. “Red” weaves through it, sign of rage and menstrual blood, color of birds, hibiscus, and sargassum. The prefix “un,” meanwhile, pervades the text, modifying verbs and gerunds to describe either colonial suffering or the radical destruction of the processes producing it.

Wielding Plath as a powerful influence, Sinclair censures male control. The “unbending” father in “Pocomania,” his daughter “forged in the fire of your self,” bellows “the name of his God,” the patriarchal Jah. Fragments from Caliban’s subjugated speech evoke colonialism. A white male choir intones the “unquestioning” givens of a world maintained by white supremacy, “lacquered and calm.” The god who rules woman “aches to stick an ache in my unmentionables.” Lovers seek possession, like Jefferson learning “how to belittle a thing.” One “ached to be inside, / thought he deserved to claim it.” Men are reptiles, predators: “the spotted lizard waits on my meagre life.”

In this patriarchal postcolonial world, black female becomes object, “helpless in the chicken wire of my soul,” the body “an open wound,” danger and goal. Menstrual blood brings self-exile, “whole selves flushed away.” “One girl” is “branded woman overnight.” An “I” knew “what it was to be nothing / Bore the shamed blood letter of my sex / like a banishment.” Another asks, “How does it feel to be a problem? The mute centuries shatter in my ear. / The aimed black spear. This body, a crisis.” In Jamaica and America, anatomy is destiny: “Woman, wound.”

But these personae flout their limits, fusing body and language to avenge their suffering. They appropriate monstrosity, transforming into cannibals with teeth for hearts, mermaids drowning unsuspecting males. Eve as Anaconda threatens, “Call me murderess.” She is “Venus-trap,” her womb empowered receptacle (“Womb. I boast a vogue sacrosanctum”).

Finally, Cannibal’s personae commandeer “the master’s tools” for their indigenous voices, “furred in dialect,” evoking “the simple language of our cannibal sea.” The “I” becomes a “wild diviner,” “incorrigible,” wrestling with an “onerous verse,” aiming “to tack it down, / the indefinite I, I, iamb; to tease this venom out—its cerasee vine grown thick as my hair.” As iamb shapes “I,” a unifying self acquires a mighty voice. By section 5, “Crania Americana,” Caliban’s snaky female avatar, “predator coiled eager at the edge / of these maps,” prepares to dismantle “the master’s house” with the syncretic tools of exile: “Master, Dare I / unjungle it?” Teasing out their venom, these incantatory “songs” redeem the voice of Caliban and of all those “cannibals” spawned by Western conquest.

Michele Levy

North Carolina A&T University

Get the book on Amazon or add it to your Goodreads reading list.