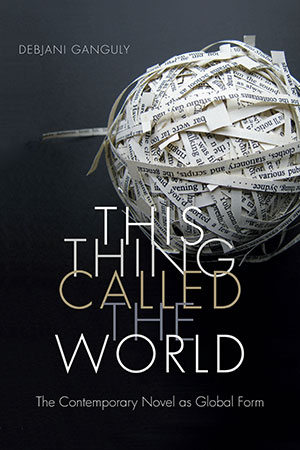

This Thing Called the World: The Contemporary Novel as Global Form by Debjani Ganguly

Durham, North Carolina. Duke University Press. 2016. 300 pages.

Durham, North Carolina. Duke University Press. 2016. 300 pages.

This is a brave book, a valiant and valuable book, that seeks to characterize post-1989 fiction as ekphrastically humanitarian. One might cavil at some of Debjani Ganguly’s theoretical formulations; one might question some of her analyses. But there’s no question about her devotion to the novel as an instrument for good; there can be no question about her diligent attention to the vast corpus of contemporary fiction; and there can be no doubt about the importance of addressing this book, arguing with it, corroborating it, modifying it, understanding it, with all its virtues and its limitations.

Her thesis is that, because of new technologies (the Internet, World Wide Web, smartphones), distant sufferings can now be intimately witnessed all over the world, and that this witness must sensitize the world to the agony in any one locality. Her title, This Thing Called the World, comes from Martin Amis’s reimagining of Mohamed Atta’s conception of the World Trade Center, which was spectacularly destroyed on September 11, 2001.

Ganguly points out that Atta was not an instrument of ideology or politics: he did not belong to an organized terrorist group. His act was a display of resentment. But where I would differ with Ganguly is this: Atta did not resent the world but, rather, the imposture of Western financial interests representing themselves as “the world,” as if the disenfranchised, the underdeveloped, the poor did not need representation and could be embodied by an august edifice built for, and in praise of, capitalism and corporate wealth.

Among the novels and works of fiction that Ganguly analyzes incisively, some more apposite than others: Ian McEwan’s Saturday (2005); David Mitchell’s Ghostwritten (1999); Salman Rushdie’s Shalimar the Clown (2005); Michael Ondaatje’s Anil’s Ghost (2000); Janette Turner Hospital’s Orpheus Lost (2007); Don DeLillo’s Falling Man (2007); and Joe Sacco’s Footnotes in Gaza (2009). A glaring omission in this list of “world novels” since 1989 would be Haruki Murakami, who would certainly top many a list of world novelists writing and publishing since 1989. Perhaps Murakami’s omission is salient because, compared to those that Ganguly considers, Murakami is least occupied with the catastrophes, the genocides, and the terrorist attacks that preoccupy the world novelists—the melancholic witnesses, as she calls them.

Her emphasis on post-1989 fiction hinges on her emphasis on that date, not as chronos but as kairos: she means the date “to signal a significant shift in the evolution of the novel. I evoke the period around 1989 as a critical threshold of the ‘contemporary’ that contains within its intensified temporarily developments from the 1960s to the present.” Ganguly thinks of (1) “the geopolitics of war and violence since the end of the cold war”; (2) “hyperconnectivity through advances in information technology”; and (3) “the emergence of a new humanitarian sensibility in a context where suffering has a presence in everyday life through the immediacy of digital images.”

Reading this book, I was haunted by the pronouncements of Mencius on his sense of ren 仁, which has been wrongly and routinely mistranslated as “benevolence.” The concept is more basic than that: it reminds us that each human being is descended from two people, and each of those parents is descended from another two people (hence the word 仁 consists of the graph for human and the graph for “2”). The consequence of this sense of humanity is the realization that all humanity is, somehow, related (one of the expressions in Chinese for “everyone” is dajia 大家, which means, literally, “big family”). Ganguly’s assertion, with which I agree wholeheartedly, is that a novelist’s mission is not to judge but to understand, not to dismiss the unspeakable but to empathetically comprehend what it is like to behave in any manner, including behavior that many characterize as “inhuman” or “inhumane.” The novelist’s mission embodies the ideal that the Roman playwright Terence enunciated when he had a character say, “Homo sum, humani nihil a me alienum puto” (I am human, and nothing of that which is human is alien to me). A novelist is this kind of human, who is not alien even to the vilest acts of human beings.

Ganguly has written an important book, a provocative book, a sensitive book. Perhaps, in the spirit of discourse, she won’t object to some corrections and some animadversions. She writes of the “five or six world languages—English, Mandarin, Arabic, Spanish, French, and Hindi. “Mandarin” is an oral dialect of Chinese: millions of people speak “Mandarin,” but no one writes in “Mandarin”: the Nobel Prize winner Mo Yan, for example, comes from Shandong province and speaks Shandong dialect, not Mandarin; just as Mao Zedong spoke Hunan dialect, and Deng Xiaoping spoke Sichuan dialect; but they all wrote in Chinese.

I question Ganguly’s emphasis on visual witnessing. Cognitive scientists have researched visual witnessing as distinctly unreliable (see The Invisible Gorilla), and perhaps Ganguly does not give sufficient weight to the numbing effect of so much human cruelty that appears in the media. Her prose may be more accessible to academics whose tolerance for jargon is greater than mine, but I had to cancel my normal understanding of “remedial” or “remediation” because Ganguly means by these words, specifically, “rendering in another form.”

These animadversions aside, I do not begrudge the time reading this thoughtful analysis, not only of the post-1989 world novel, but a sensitive report on the temper of our times.

Eugene Eoyang

Bloomington, Indiana

Get the book on Amazon or add it to your Goodreads reading list.