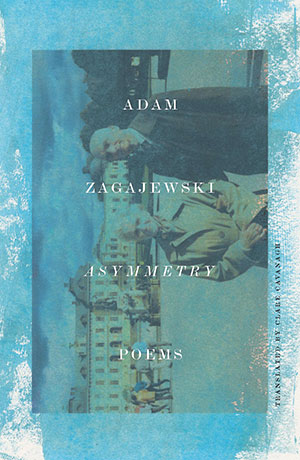

Asymmetry by Adam Zagajewski

New York. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. 2018. 96 pages.

New York. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. 2018. 96 pages.

This stunning new volume from Adam Zagajewski deserves to be read by anyone who has wondered how language can describe absence. It is a classic conundrum. And Zagajewski’s humane, welcoming voice is just the one to think through it: he is a poet who eschews an academic tone, refuses to play linguistic games, and declines a podial manner, although he insists that the lyric can bring us above quotidian life even as this life grounds and innervates it. There is a reason Zagajewski has found so many readers—he is open to us. He makes no assumptions about his readership, no exclusions.

The volume begins with the poem “Nowhere,” which in turn begins with the poet returning from his father’s funeral. His gaping loss obviously informs the disorientation that spirals through the poem. He feels he is “nowhere,” he belongs “nowhere,” and his pain is itself “nowhere,” which is the key to this paradox. He offers plenty of details that place him in space and time and give him what we call an identity—yet our commonplace belief is that identity is formed through tangible, explicable alliances and experiences. How can such identity account for absence, grief? An American cashier asks the speaker where he is from. She is expecting a statement of belonging, so she—and we—can situate him in a named location. But, he tells us, he had forgotten: “I wanted to tell her / about my father’s death, then thought: I’m too old / to be an orphan.” The socially correct answer, Poland, is not correct for the psychology of one experiencing the vertiginous effect of loss. He is coming from a funeral, from a brief encounter with the land of the dead, from the long land of memory where his father currently lives. This sense of being and belonging nowhere, of orphanhood in many guises, pervades Asymmetry and gives the volume a mission: to struggle toward an answer to her question and to redress this feeling of pain as well as to inhabit it truthfully. Not to pretend that the loss does not exist; not to pretend that it does not hurt.

It can, however, be transmuted, and Asymmetry shows us how the basic experience of loss can take on multiple guises. For example, the loss of the city of Lvov that preoccupies much of Zagajewski’s work is now given new resonance as we view it through the more acute personal loss of his parents. The loss of a visionary moment is another guise, yet without this loss a poem could not be written. We all grapple with the loss of our childhoods but also more complexly with the loss of our former selves: How would the child-me regard the adult-me? How can our minds comprehend the irrational pattern of what has been lost and what still remains?

These poems know that they are governed by a tangled logic. They also, crucially, realize that human life is not always governed by any perceptible logic and do not try to explain the inexplicable to their readers. This is one of the most gratifying aspects of Zagajewski’s work—it does not pretend to know every secret, to have every answer. Despite the poet’s defenses of ardor, seriousness, and high art, he never lectures or condescends to us, never holds himself above our own human level.

The poems in Asymmetry are among Zagajewski’s best: precise yet grand, contemporary yet timeless, suffused with emotion yet not maudlin, and never self-satisfied. If this is the poet’s late style, we can only wish there will be more.

Magdalena Kay

University of Victoria