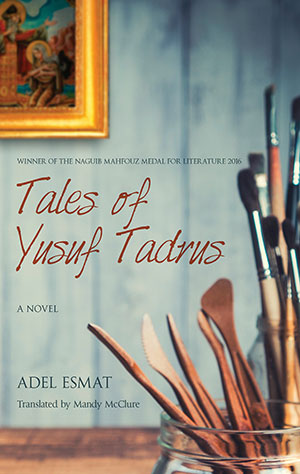

Tales of Yusuf Tadrus by Adel Esmat

Cairo. American University in Cairo Press. 2018. 216 pages.

Cairo. American University in Cairo Press. 2018. 216 pages.

It’s no accident that the epigraph to this novel is from Nikos Kazantzakis’s Report to Greco: “I said to the almond tree, ‘Speak to me of God.’” Kazantzakis’s book is a spiritual autobiography, which is short on facts but focuses on ideas, referring to the spiritual teachings of Christ and Buddha, Lenin and Odysseus. Tales of Yusuf Tadrus is a bildungsroman, although the artist-narrator, Yusuf Tadrus, reveals the secrets of his entire life, not just as a young man. Like Stephen Dedalus in Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, Tadrus resembles Odysseus on a journey of profound self-discovery. However, Adel Esmat uses Christian mythology, not Greek allusions, to tell Yusuf Tadrus’s story, a Coptic man from a humble family, living in the provincial town of Tanta as a child in the 1960s.

Yusuf is a bit of a vagabond and a rogue, and we have the feeling that everything he tells us might not be strictly true. He exaggerates to give the tale flavor. Esmat draws on the Egyptian tradition of oral storytelling. Rather than plot, the driving force of his novel is Yusuf’s voice, which makes the narrative compelling: “Listen, the human being is a web of threads. I often reflect on my life. I arrived bound to a boy drowned in the Nile years before my birth; to a father who felt inferior to those who read and write, took pride in himself, and locked up his feelings in his heart; to a mother who wanted to dedicate herself to the Lord. All of these unseen threads came together to form your brother Yusuf Tadrus.”

Each chapter is a thematic vignette, which begins with his brush with death at seven years old. Mandy McClure has rendered the strength of this novel into fluid, idiomatic English, as if someone were telling a story in a café. Yusuf’s strange dream, poetic yet immediate, draws the reader in. From an early age, Yusuf has an attraction to light, color, and a passion for art. Much of the novel revolves around universal questions: What is the authentic life? Who am I? While he dreams of studying art in Paris, Yusuf settles for an art school in Alexandria, which awakens his thirst for learning.

For financial reasons, he must leave the art school and returns to Tanta. Pressured by social conventions, he marries early and has two children. Because he feels constricted by domestic concerns, he has an affair with a Muslim art teacher. Sexual relations between Muslims and Christians can lead to murder. Rumored to be a sexual predator, he is banished by the school and the community to Sinai, where he succumbs to self-loathing and guilt.

It is only when Yusuf returns to his wife and children and a more conventional existence and faces his demons that he begins to heal from his depression. In his forties, he starts “painting the reservoir of his dreams.” He changes his attitude toward life, himself, and has a greater awareness of the creative process. True to his inner awareness, he makes “authentic art.” He rejects the trendiness of the art world and finds serenity in the companionship of his long-suffering wife, Janette, and their family.

Even though The Tales of Yusuf Tadrus is a novel, it has the feel of a thinly veiled autobiography. Other books in Egyptian literature, like The Days (1933), by Taha Hussein, and A Sparrow from the East (1938), by Tawfik Al-Hakim, have explored the “education of an artist or intellectual as a young man,” especially in France. One is surprised, though, by the ending of the Tales of Yusuf Tadrus, since the hero, Yusuf, seems to accept his lot but then suddenly decides to follow his adult children to America. The novel ends on a grim note about the future of Egypt: “Tell me, for God’s sake, when will the light shine on this country?”

Gretchen McCullough

American University in Cairo