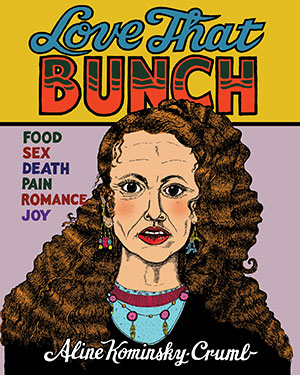

Love That Bunch by Aline Kominsky-Crumb

Montreal. Drawn & Quarterly. 2018. 211 pages.

Montreal. Drawn & Quarterly. 2018. 211 pages.

The reservoir of material for comedy, either stand-up or on the page, is often autobiographical, and this is certainly the case for Aline Kominsky-Crumb (yes, she is married to the R. Crumb, who has his own autobiographical comic reservoir). Kominsky-Crumb first hit the comics scene in San Francisco in 1972 with Goldie, published by the Wimmen’s Comix Collective. Goldie, a clear precursor to Bunch, is neurotic, self-deprecating, and striving. Bunch followed soon after, and this volume opens with a comic from 1976 titled “The Young Bunch, an unromantic nonadventure story.”

In this early piece, Bunch, drawn in the unsteady, wavering lines that characterize all Kominsky-Crumb’s work, is depicted as the yearning girl at the dance longing to be noticed by the popular boy, Al. They go off together, and his thought bubbles clearly indicate that his goal is sex, while hers is fantasy romance. The evening goes his way in what is patently a rape scene with graphic depictions of genitalia. This marks the reader’s introduction to the author’s desire to shock, enlighten, challenge, and provide cultural critique.

Throughout this volume, which includes drawings from 1976 through 2013, Bunch emerges as a lens on women’s most basic insecurities, passions, reflections, and desires in the second half of the twentieth century into the twenty-first. Of course, Bunch is specifically a middle-class Jewish product of Long Island, as is Kominsky-Crumb, and her parents take great delight in her participation in “cultcher” and plot to get her a nose job just like those of her high school classmates. “Rhinoplasty” is one of Kominsky-Crumb’s better-known comics, and in it Bunch sets the tone for the rest of her life by resisting the pressure to conform, reveling in her “original” face, which looks a bit like Joan Baez’s or Buffy St. Marie’s. It does help the reader to have some familiarity with the cultural icons of the 1960s, ’70s, and ’80s.

Bunch’s parents are specific to a place and time, as are her relatives, but the underlying family dynamics and pressures are applicable across cultures. Her parents are often at each other’s throats, with their daughter as witness. She fantasizes escaping her childhood environment for a more exotic artistic life, and seesaws between despair over her looks and arrogant pleasure in her body. Bunch relishes female power in all its complexity—in one continuing motif, Kominsky-Crumb splits Bunch in two, Bunch and her alter ego, Mr. Bunch, the masculine self who lives inside of her. These many contradictions and textures of Bunch help create a rounded, visceral character.

Most important is how Kominsky-Crumb plumbs the ways women of the era (and perhaps any era) struggle with insecurity, the images they project, their own power, and their sexual desires. She is among the first comic artists to grapple with the complexity of the female person and persona. As such, Bunch is iconic, always outrageously in your face, sometimes very funny, sometimes cringeworthy, sometimes lovable, and sometimes revolting (even to herself), but always and forever authentic.

Rita D. Jacobs

New York City