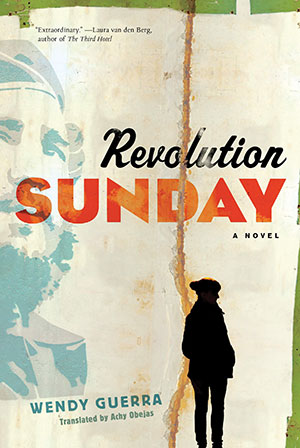

Revolution Sunday by Wendy Guerra

Brooklyn. Melville House. 2018. 208 pages.

Brooklyn. Melville House. 2018. 208 pages.

Betrayal, at all levels, is the essence of Revolution Sunday by Wendy Guerra. Cloe, a novelist and poet, is betrayed at all levels, from all directions. Betrayed by the people she loves: her mother, her housekeeper, Márgara, and her lovers. Betrayed by her neighbors who spy on her and report her movements and activities to the authorities. Finally, in an ironic twist, she is betrayed by Cuba, her home, her raison d’être, her heart: “without Cuba I don’t exist. I am my island.”

Cleo, the narrator of Revolution Sunday, lives in her family home in a disintegrating Havana, the capital of an equally disintegrating Cuba. She is a passive victim of constant surveillance, control, and dictator-approved abuse. She is surrounded by people who protect themselves from the authorities by spying on her (and everyone else) and reporting their discoveries to the police, who visit her home on a regular basis, taking with them, when they leave, her work, her photographs, her computers, and anything else that they might use to prove that she is a dissident.

Yet she stays in the house after the death of her parents in a suspicious car accident and retreats into the cage she has created for herself. She is locked inside her cage, inside her house, inside her crumbling city. The reality she has created is soon destroyed after the appearance of a Hollywood actor, Gerónimo, who has come to interview her regarding her father, Mauricio Antonio Rodríguez, “el macho”, for a film he is making. Cleo’s whole life and history, as she knows it, is called into question by this investigation of her father’s life, leaving her shaken to the core as she moves through the falsified facts and fictions of her life.

Indeed, Revolution Sunday is a dark, disjointed narrative with fragmented episodes and questions with no answers. Cleo moves seamlessly from Havana to Paris, to Mexico City, to Spain, to the United States, to Cannes without explanation of how she managed such trips with the authorities hot on her heels at every turn. As she muses, travels, and enters and exits one tumultuous relationship after another, it becomes apparent that she is a prisoner of her own personal situation as well as the political situation in Cuba.

Her narrative and the poetry within it illustrate this imprisonment: “I’m trapped, full of doubts”; “when you’re born in captivity, you have a very precise set of gestures”; and “I’m imprisoned, completely imprisoned.” Throughout the novel, Cleo refers to Havana as home, yet she admits to herself that she needs to hide behind the disguises created by clothing or masks. The falsification of her own identity and the way that she alternates between her love for Cuba (“Cuba looks so small down there, while it’s so big inside me . . .”) and her desire to be free of the constant surveillance is the ultimate betrayal.

Cleo is a sad person living a sad life. Nothing she does ever alleviates her sadness and, as she experiences repeated betrayals, she only imprisons herself more securely inside the cage she has created for herself. Revolution Sunday ties the realities of Cuba with the insecurities of her people. To be constantly afraid of what the authorities might do next, coupled with the frequent traveling to free democratic countries across Europe and the Americas, creates a paradoxical situation through which Cleo finds it difficult to navigate.

Janet Mary Livesey

Norman, Oklahoma