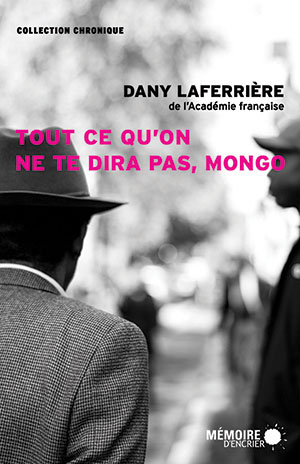

Tout ce qu’on ne te dira pas, Mongo by Dany Laferrière

Montreal. Mémoire d’encrier. 2015. 299 pages.

Montreal. Mémoire d’encrier. 2015. 299 pages.

Tout ce qu’on ne te dira pas, Mongo (Everything they won’t tell you, Mongo) is Dany Laferrière’s first new book since his induction into the Académie Française. An immigrant to Montreal born in Haiti, Laferrière is the only writer in history from either of these countries to have joined the Immortals. In keeping with his now-consecrated place in francophone literature and with the tone of his last two books, Laferrière’s alter-ego narrator in Mongo is no longer the enfant terrible of his earlier works but a jaded sage dispensing advice to the younger generation. Here the narrator (which in classic Laferrière style both is and is not the author himself) bestows his knowledge and experience upon the fictitious Mongo, a recent immigrant to Montreal from Cameroon.

Hodgepodge in structure, the first half of Mongo intersperses observations from the narrator’s notebook, transcripts from his Sunday-morning cultural commentary radio program, and scenes from café life in which he chats with Mongo and his white Quebecoise girlfriend. While the café scenes bring Laferrière closer to the fiction he used to write, the majority of the book features short treatises on different aspects of Quebecois society and history such as the Quiet Revolution, the weather, and attitudes toward immigrants. Haiti is not completely absent, as Laferrière often makes comparisons between Quebec and his homeland or more broadly between “the North” and “the South.”

All these reflections lead up to a guidebook destined for Mongo entitled “How to Infiltrate a New Culture” that comprises the second half of the book. This hybrid structure results in several repetitions that slow the pace of the volume’s three hundred pages, as compared to Laferrière’s novels, which inspire a breathless reading in one sitting. While not as provocative as his previous work, Mongo still has moments of humorously biting social critique, particularly in the section entitled “A Short Glossary for New Arrivals,” where we find, for example, a Quebecer defined as “an individual ready to die for a language without even trying to write it well.”

Mongo will most appeal to readers with an interest in immigrant literature, in a unique outsider view of Quebec, or with a continuing interest in Laferrière’s career. Those readers new to Laferrière would do better to start with some of the earlier books, which originally earned the author his place in the Académie.

Corine Tachtiris

Earlham College