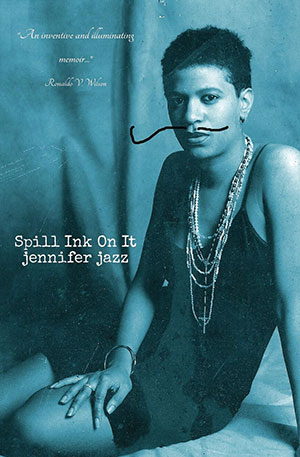

Spill Ink on It by jennifer jazz

New York. Spuyten Duyvil. 2020. 222 pages.

New York. Spuyten Duyvil. 2020. 222 pages.

SMART, BITING, VIOLENT, and often perplexing, this memoir is reminiscent of Jamaica Kincaid’s A Small Place. Beyond the authors having Antigua and matrophobia in common, jazz, like Kincaid, reveals truths in the work that others might well consider taboo. Spill Ink on It is an excellent personal, social commentary on life, spanning her early years of the 1960s through the 1980s, in the US and abroad.

Divided into four sections—“Amber,” “Green,” “Blue,” and “Red”— the memoir charts the development of the author from early adolescence until twenty-two years of age and zeroes in on life in New York during the 1980s. A high school creative-writing teacher advised jazz to “organize your moods into colors”—and the reader will invest in the author’s many moods. Her stories and her facility with language are compelling. She is raised with two other siblings (and later relatives from the Caribbean) in a family of women: Great-Grandmother (Granny), Grandmother (Nanny), a self-absorbed mother (“she gets flustered when I ask for advice”), and aunts. From each she learns life lessons that aid or impede her quest for an identity that suits her temperament.

Always the rebel, she is an outcast at school; she drops out of a liberal arts college after the first semester, has trouble keeping a job, travels abroad in search of a man she is convinced she loves, and eschews money (read as capitalism) in general. Later in the work she declares herself androgynous and enters into a brief lesbian relationship.

One of the most compelling aspects of the memoir is the author’s observations on life. Of being called the N-word she observes, “It would be the first but not last time some random antagonist would try to redeem history where I’m down and they’re standing.” Of the violence in the country she reveals, “I already know that the gun will be the only hero this country will ever have.” She calls Margaret Thatcher “an unchecked disease” as immigrant violence rages in London. She even supplies commentary on the Caribbean and black American tensions of the era.

Then there is the host of unusual characters, her association with the Haitian American artist Jean-Michel Basquiat, and her joining the group the Guerrilla Girls, for which she is best known.

The work often reads as impressions committed to a diary and is often as raw as it is rewarding.

Adele Newson-Horst

Morgan State University